What to Do When You Know Exactly What to Build

Recently, my business partner and I had an idea to start building a fundraising product. I’ve started 3 different companies, invested in over 30 companies, and advised even more. When it came to building a product, I had a couple of ideas about what to build, and a lot of experience to draw from.

That’s why we ignored it all.

Instead, she and I focused on learning by researching the problem. We sent out early-access surveys. We asked founders how their fundraising was going, what incubators they found most exciting, and who they got their fundraising resources from.

Source: Twitter

Source: Twitter

When you think you know exactly what to build for a new product—or even how to expand on an existing one—exercise extreme skepticism with all of your assumptions and convictions.

One of the hardest lessons for repeat founders to learn is that expertise is overrated. If you know what you should be building, then you’re making progress linearly from your past experience. The most innovative products come from the unexpected things you find when digging into the problems.

These are a few of the most common assumptions that people make when they follow their instincts around building a product:

- Because something happened in the past, it will happen again in the future.

- Your customer’s problem is the same as your own problem.

- The market will support what you want to build.

We’ll walk through each assumption, along with strategies for building habits to get past them.

1. Don’t Assume the Past Predicts the Future

When you know exactly what to build, the first assumption that you’re making is probably that you’ve learned something in the past that you can apply to what you’re building today. It’s a dangerous fallacy.

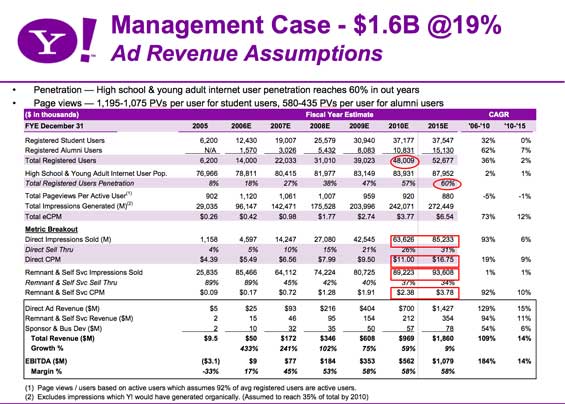

Here’s an example: Back in 2006, Yahoo was considering acquiring Facebook to the tune of $1B. The folks at Yahoo had done their math, and they estimated Facebook’s value based on its own user base of college students at the time. They predicted that by 2010, Facebook would hit 48 million users. The slide below shows Yahoo’s internal projection of Facebook’s growth:

(Source: Andrew Chen / TechCrunch)

(Source: Andrew Chen / TechCrunch)

Facebook’s actual user base in 2010 was closer to 350 million. Yahoo assumed that Facebook’s future growth would follow how it grew in the past. Yahoo put together a billion-dollar offer based on their own experience monetizing traffic with ads. They were deeply wrong.

A lot of people make this mistake:

Assumption: Past experience indicates the future.

As people, we’re conditioned to think in straight lines. We think that the future will fall into place in-step with what we’ve experienced previously. In doing so, we limit ourselves to what’s already been done.

Challenge your inherent assumptions by asking:

What are all the different ways that I’m wrong?

If all of your data looks good, that’s when you should be extra cautious. Building a good product requires equal parts paranoia and systematic iteration.

In a talk at SXSW, Peter Thiel explained why Mark Zuckerberg turned down $1B from Yahoo: “[Yahoo] had no definitive idea about the future. They did not properly value things that did not yet exist, so they were therefore undervaluing the business.” Looking at the data, Yahoo assumed that Facebook’s growth was predictable based on past experience. In reality, Facebook’s college student base was just a launching point for something much bigger.

How To Do It

Early on in the life of your product, you’ll be tempted to dig into metrics, like how many daily or monthly active users your product has. You’ll also want to run a bunch of A/B tests, and lean on data to inform all of your decision-making. The reality is that early on you won’t have enough data to make statistically significant decisions.

Focus on the things you do know:

- Test your riskiest assumptions first: Leo Polvets, a VC at Susa Ventures calls startups “collections of risks.” He points out that the best way to get past this is to “address the biggest risks as quickly and as thoroughly as possible.” If you waste time and resources on small, insignificant risks, you’ll get caught with your pants down when the big ones come. To de-risk your business, map out all of the different risks around what you’re building on a scale of 1 (high risk) to 5 (low risk).

- Jump on opportunities: When the travel and expense management tool Concur was getting acquired by SAP, the team at Expensify saw an opportunity to step in and win over the competition’s customers. They spent an entire weekend building an integration that would allow Concur customers to switch painlessly to Expensify. Expensify CEO David Barrett points out that you won’t always have time to A/B test your messaging or weigh all of the implications. The important thing is to “keep an open mind, consider all the opportunities, act decisively on those that excite you, and move on.”

- Be skeptical around your data—especially when it looks too good to be true. Say that you set up a minimal landing page with some copy and an email sign-up to validate your idea. If you’re seeing high email sign-ups, look to see how quickly people are bouncing from the page to gauge if they’re actually engaging with your copy. Facebook VP of Product Design Julie Zhuo recommends finding countermetrics by asking yourself, “What else can I look at to convince me that these results aren’t as good as they seem?”

2. Separate the Problem from the Solution

When we were doing customer research for KISSmetrics, our web analytics product, we stumbled across a really interesting problem that a lot of our customers had: getting feedback from their customers. It wasn’t a problem that fell into our core product focus, but it did lead to an entirely new product called KISSinsights.

A lot of people think:

Assumption: You research the problem to find solutions for the problem.

This tends to just cause more problems. When you’re doing research around customer problems and pain points, you’ll inevitably start thinking about ways you might solve them, but this introduces your biases into the mix. This is a well-known principle of psychology, known as confirmation bias. Confirmation bias says we tend to seek out information that confirms what we already believe.

When you think you know what the problem is, ask yourself:

What user stories do we get from the data that we believe to be true?

Stay in problem land. It’s already difficult to interpret data—pay extra attention to what the data actually says vs. what you believe it says.

As Cindy Alvarez, our research lead at KISSmetrics, writes: “When customers keep telling you something, you’d be crazy to ignore them.” Doing research for KISSmetrics, we originally set out to validate the need for better web analytics. As part of the customer development process, we asked people what pain points they had around web analytics, and what tools they were using to solve them.

It turned out that getting qualitative feedback was huge problem for a lot of our customers. It wasn’t directly related to what we were building at KISSmetrics, but so many customers shared this problem with us that we decided to pursue it further. We doubled down on this by doing another 20 customer interviews, specifically around the problem of getting good qualitative feedback.

By listening carefully to the problem, we were able to rapidly create an MVP to validate customer demand, and within several months, KISSinsights was installed on over 1,211 websites. A couple of years later, Sean Ellis bought it and turned it into Qualaroo.

How To Do It

Draw out the problems by doing qualitative research, user testing, and shadowing your customers. Keep your head in the data and the problems:

- Approach your product with a beginner’s mind: In an internal memo that Slack CEO Stewart Butterfield sent to the company two weeks before launch, he wrote, “Putting yourself in [your customer’s mind] means looking at Slack the way you look at some random piece of software in which you have no investment and no special interest. Look at it hard, and find the things that don’t work.”

- Prototype with your customers: Product designers at Atlassian’s JIRA ask customers to participate in hour-long sessions where they build a prototype live in front of a customer. One designer spends 30 minutes in a room with the customer, asking questions around the customer’s workflow. Another designer listens in, and creates a prototype with Sketch. After the 30 minutes are up, they share the wireframe with the customer to get real-time feedback.

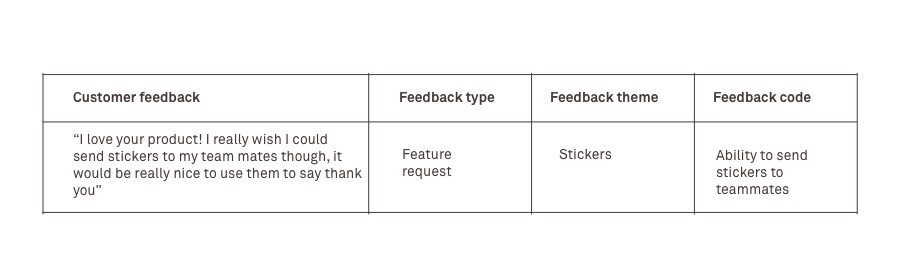

- Collect qualitative data and categorize it quantitatively. At Intercom, product managers take open-ended feedback from customers, and tag the responses into categories like “Usability,” “New Feature Request,” and “User Education.” They break feedback into themes (specific parts of the product) and codes (actionable items from user feedback), before counting how popular each piece of feedback is. This allows Intercom to prioritize its product roadmap through open-ended feedback.

3. Size the Market

3. Size the Market

Back when KISSmetrics was founded in 2008, we wanted to build a tool that would help product people track their user data—similar to Mixpanel or Amplitude today. That seemed to be the natural evolution of where analytics was trending. If we didn’t do our homework, we would have gone ahead and built out this idea—and completely missed the mark.

A lot of people figure:

Because we’re tackling a real problem that we’ve experienced, the market will support whatever we’re building.

Just because you have a great idea, though, doesn’t mean that the market will support it. When you’re convinced that the market will support your hypothesis, ask yourself:

Am I building the right thing, at the right time?

If you’re not sure, you need to take a step back and reassess everything you’re doing.

By asking ourselves this question at KISSmetrics, we were able to save a lot of time and money. We found that most companies considered product a cost-center; compared to marketing or sales, which drive revenue, product costs money. That meant that product managers had less money to spend on tools than marketers or sales people. When they did use analytics, they liked writing SQL queries to a database.

Building an event tracking database was a good idea—it just wasn’t the right idea at the right time.

How To Do It

When you’re building a new product or feature, here’s how to validate the market:

- Don’t look for market size. Look for people size. If you’re targeting product managers, for example, see how many of them you can actually call up on the phone and reach. If the people size within your target market is small, ask yourself an additional question: Is it growing?

- Schedule time to meet with prospects and customers. Qualitative feedback is great for building up customer focus in your business. Support reps aren’t the only people who should interact with customers. David Cancel, CEO of Drift, sets aside time each week to meet with customers in person where they work so he can see them in their natural environment.

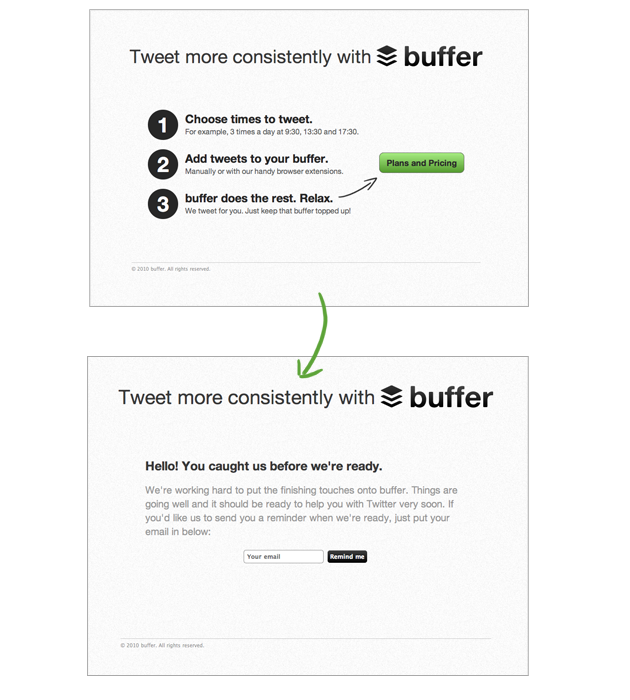

- Test the market. Buffer got started with a two-page MVP that explained what Buffer did—before their product even existed. Joel Gasciogne, CEO and Co-founder of Buffer, tweeted out a link to the page. He received enough interest that he went one step further and put up a pricing page for their hypothetical product to see if people would actually pay for it. It looked like this:

Build Habits, Not Experience

When you have experience building products, you amass learnings along the way. It’s tempting to apply these learnings to a “big idea” that you have—toward building something new that nobody has seen before. But, building stuff that people will care about isn’t just about having some big idea.

Most of the time, the hardest startup challenges have more to do with how you solve the problems than what those problems are. To do so, you have to ruthlessly root out any internal biases you have about what will and won’t work. Build up habits instead, and put systems in place that will help you test and validate lots of smaller ideas that come your way. That’s where we should be putting our creativity.