The Unexpected Rebirth of Google Glass

Few products in tech have drawn as much ridicule or outright laughter as Google Glass. But that wasn’t always the case. Back in 2012, Sergey Brin showed off a prototype of Glass at Google’s I/O conference:

A screen behind Brin projected a live stream chat between Brin and two Google engineers in a plane. Suddenly, one of them jumps out of the plane, parachuting onto the roof of the stadium where the audience is sitting. The entire event is broadcast live through the Google Glass he’s wearing.

Glass elicited an awe-inspiring response at the conference and in the press—at least initially. People were excited about it because, like the recently announced Apple Watch Series 3, it promised them a new, post-mobile way of communicating.

The tide began to turn after the Google Glass pre-release in 2013. Beyond the planned stunt, there was little that hinted at a real use case, let alone ecosystem, behind the new product. And the bad PR mounted.

Headlines like “Google Glass getting to grips with ‘geek aesthetics,’” “Google Glass will make you manly, says Sergey Brin,” and “Google Glass is always listening, assuming you have a hack” emerged to disdain. Robert Scoble famously wore them in the shower. By 2015, no one wanted to be seen wearing a pair.

But, Google Glass is about to relaunch this year—and that begs a few questions:

- Given its potential and technology, why wasn’t Glass the spectacular success many expected it to be the first time around?

- Why did it fail so dramatically?

- What made Google decide to relaunch the product, and what are they doing differently this time around?

Let’s dive deeper into the hype, death, and rebirth of Google Glass.

2009-2011: The Development of Google Glass

Glass started with a vision of an exciting new technology that would change the world.

Google had high hopes for Glass. The company wanted smart glasses to be the next big hardware platform—one as groundbreaking (and profitable) as Apple’s iPhone. The iPhone put a computer in your pocket and made it accessible through a tap and a swipe. With Glass, Google wanted to help you interface even more seamlessly with technology by putting a computer on your face.

Back in 2009, one of Glass’ co-creators Babak Parviz wrote:

“We already see a future in which the humble contact lens becomes a real platform, like the iPhone is today, with lots of developers contributing their ideas and inventions. As far as we’re concerned, the possibilities extend as far as the eye can see, and beyond.”

Parviz had been working on creating smart contact lenses, and it was this vision that he brought to the Glass project a year later. The idealistic vision around Glass’ development masked a huge blindspot: how people would actually use the product.

The team behind Glass succeeded in solving the really hard problem of creating a computer you could wear on your face. What they failed to figure out is why people would want one.

2009-2010: Google CEO Eric Schmidt approached Sebastian Thrun, a Stanford professor, to help create a lab for long-shot technology programs. Google Glass was now the first project of the infamous “moonshot factory,” followed by self-driving cars. Thrun began to put together a team of researchers, scientists, and engineers to work on early prototypes of Glass.

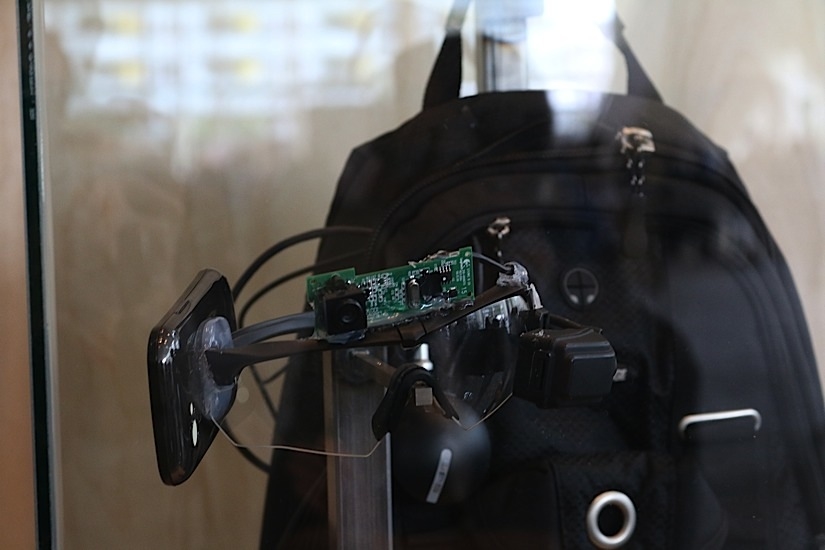

The early prototype of Glass looked like a scuba mask attached to a laptop you carried around in a backpack. It weighed eight pounds.

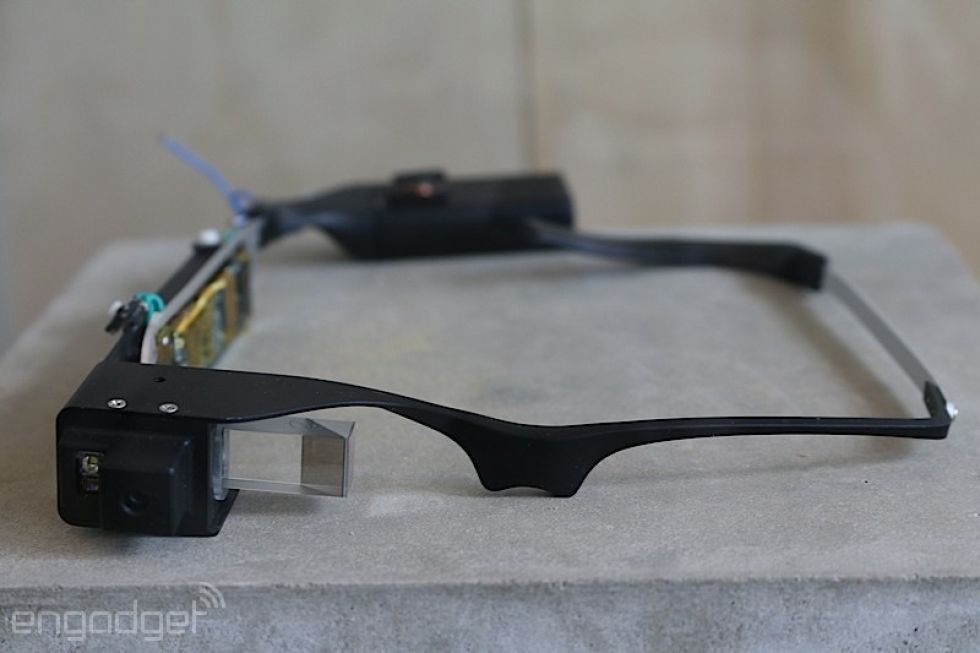

2011: The Glass team began to iterate on their early designs to make a product that was light and portable. They removed the laptop in the backpack, and began engineering custom optical displays and circuitry.

Image Source: Engadget

Image Source: Engadget

The people behind Glass were veteran researchers and engineers with a lot of expertise in wearable computing. One Glass co-creator, Astro Teller, had previously worked on an armband that tracked exercise and sleep. Parviz was the other co-creator, who worked on integrating digital displays and monitors into contact lenses. On a technical level, the team was packed with rockstars.

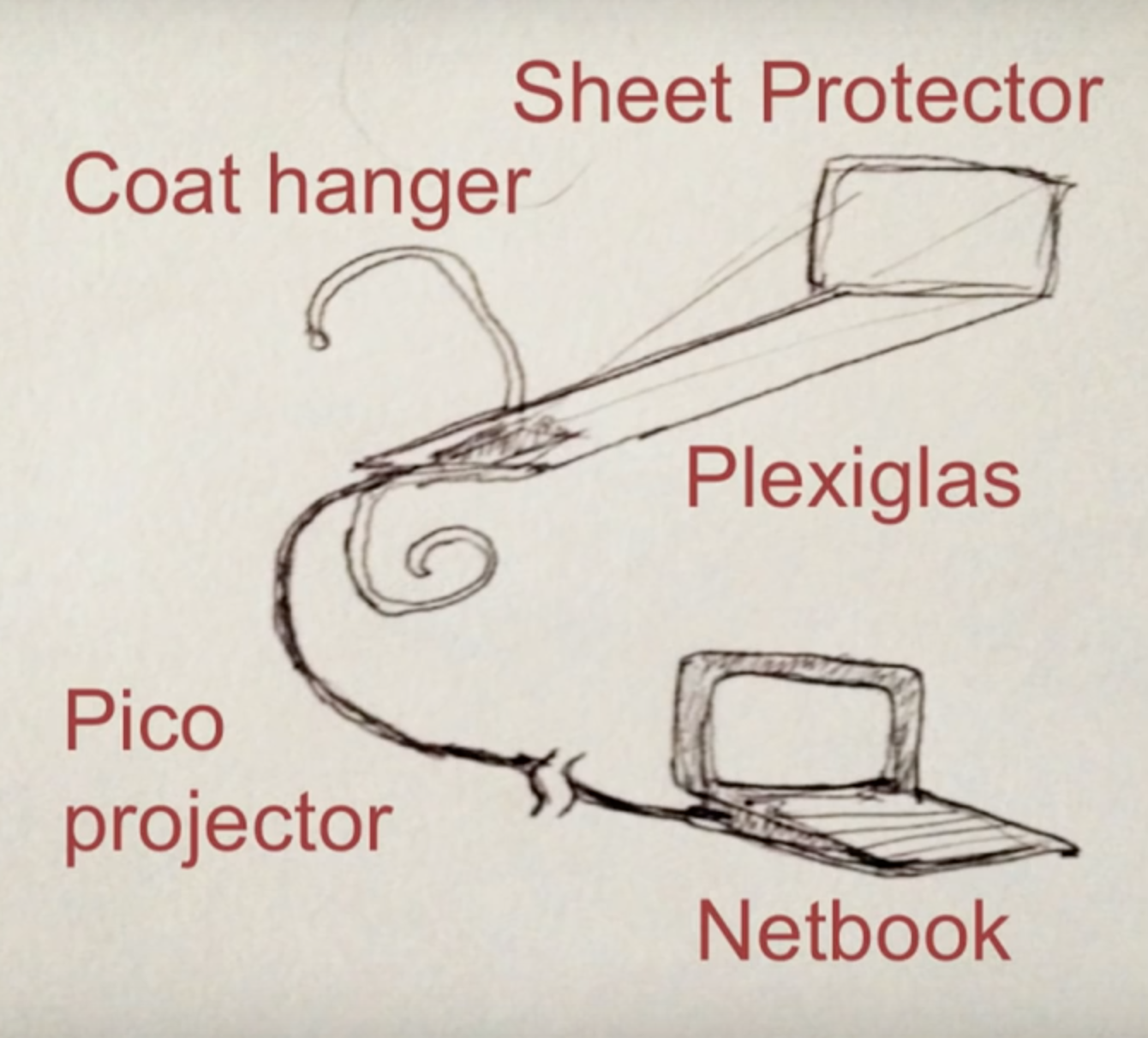

They got to work on Glass in complete secrecy from the rest of Google. Early on, the team’s focus was figuring out how people would interface with the product. They broke down the basic user experience of Glass through a series of prototypes, using a pico projector connected to a laptop to project a display onto a sheet. Once they sorted out the kinks of the interface, they focused on refining the hardware to be light and portable.

What they hadn’t quite figured out was who their target audience was. The engineers couldn’t agree on how to position Glass. One group believed it should be a consumer product that people would wear all day. Another group believed Glass should fulfill “specific utilitarian functions.”

Google co-founder Sergey Brin figured that these debates would be ironed out by launching Glass early and iterating based on feedback. This approach had served Google well in the past with software products like Gmail and Docs, so they assumed it would work again. Brin was eager to get Glass out into the wild.

By 2012, a team of designers and engineers at Google’s moonshot factory were ready to show the world a prototype, even if they didn’t yet know what the world would use it for.

2012-2014: The Initial Launch (and Failure) of Google Glass

That brings us to the moment Sergey first demoed Glass in 2012. A couple months earlier, Google had previewed Glass to the public for the first time through a futuristic concept video:

The video walked you through a scenario wearing Glass: Imagine waking up from a nap. You flip through your calendar while pouring a cup of coffee, check the weather, and text a friend—all without looking at a computer or smartphone screen. That was the early promise behind Glass in promotional videos and at the I/O conference.

The early reaction was overwhelmingly positive. Time Magazine named Glass one of the Best Inventions of 2012. Tim O’Reilly tweeted: “I suspect that Google Glass may be a technology milestone to surpass the iPhone.”

The public had high hopes for Glass—after all, it was being created by Google! But Glass signaled a big shift in approach from the Google that people knew and loved.

A16z Partner Benedict Evans put it the best in a piece called “Glass, Home, and Solipsism”:

“The old Google rejoiced in sending people away from the site as fast as possible, because the result mattered, not the search. Glass points to a risk of forgetting that.”

Google Search provided clear utility for customers. It helped them find exactly what they were looking for on the web by sending them away from Google. In contrast, the consumer version of Glass was asking people to come in the front door and stay. It wanted to replace the smartphone and become your interface for everything—from sending texts to reading the news. The problem was that it didn’t seem to do anything better than a smartphone.

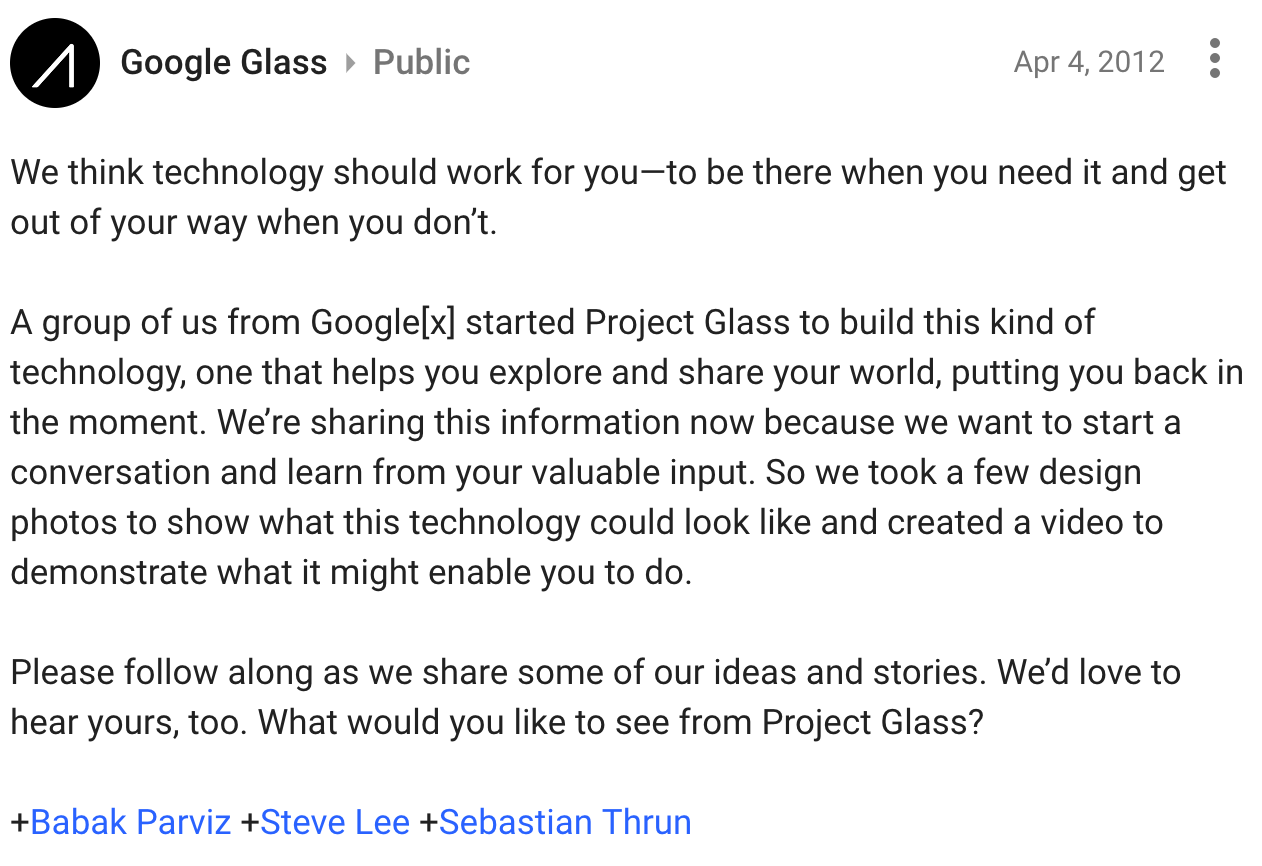

2012: Glass is officially announced in April 2012, with a blog post on Google Plus and a concept video. Later that year in June, Sergey Brin shows a live demo of Glass at Google’s I/O keynote conference. In September, Glass is featured on models at New York Fashion Week. The resulting media blitz whipped up huge excitement around the product.

Here was the Google Glass announcement on Google Plus:

Google co-founder Sergey Brin and fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg wearing Glass on the fashion runway.

2013: Google creates the “Glass Explorers” program, where people can apply to test an early version of Glass. The early-access campaign was fueled through Twitter. Here’s what the application for the Glass Explorer’s program looked like:

While Glass was still a prototype, the hype behind it meant that everyone saw it as a finished product. They weren’t impressed. Pretty soon, public perception around Glass radically shifted.

2014: Public backlash against Glass ramps up. The product is parodied everywhere from The Simpsons to The Daily Show. Here’s an example of a Comedy Central skit:

Glass’ public launch, originally intended for 2014, was delayed indefinitely.

The “Glass Explorers” program was meant to help Google iterate on the product based on real user feedback. While this strategy had proven itself for products like Gmail, Sheets, and Docs, it didn’t translate to hardware—in large part due to the media circus around Glass.

By mid-2013, as Glass was making its way into the real world, things started to change. The public was not only less interested in Glass, but also legitimately concerned about the implications of the technology. Here were some of the big challenges for Glass:

- At a whopping $1,500, few consumers were actually willing to pay for Glass. Due to the restricted nature of the pre-launch, most couldn’t buy one even if they wanted to. For its early life, Glass was only accessible to wealthy tech professionals and other early adopters.

- The marketing blitz around Glass, from the I/O keynote to featuring Glass in fashion shows, created massive expectations around a product that was still a prototype. Upon launch, many of these features shown off in Google demo videos—video conferencing, voice response to text messages, and more, were still in development and unavailable. To use Glass, it had to be tethered via bluetooth to an Android phone while the product itself frequently crashed and ran out of power. One of the only features that worked well was the camera and video recording feature.

- The camera and video features of Glass were seen as an invasion of privacy, causing a major PR crisis for Google. When someone looked at you wearing Glass, it felt like they were pointing an iPhone at your face.

- Perhaps the biggest issue was that Google failed to present a convincing use case for Glass that proved, for most people, that their smartphones couldn’t do better. Glass lacked a “killer app” like Instagram or Angry Birds that hinted at its platform potential for consumers.

In contrast to how the public and media were originally talking about Google Glass, now the headlines sounded more like this: “Google Glass is the Worst Product of All Time” and “The Verdict is In: Nobody likes Google Glass.” In one incident, a woman wearing her Glass to the bar had it forcibly removed by another patron. Everyone else at the bar cheered. While Glass started out strong, the product was ultimately seen as a symbol of tech privilege and invasiveness. Glass users were dubbed “Glassholes” and publicly shamed.

In the short span of a year, Glass had gone from a product that was supposed to make the smartphone invisible to one that was a source of public ridicule. By November 2014, nine out of 16 Glass app makers stopped working on projects for Google Glass because there wasn’t adequate market demand—or even interest. Glass co-creator Babak Parviz left Google for Amazon, followed by other important team members. Publications started to report—prematurely—the death of Glass.

While the team behind Glass still believed in the product’s potential, it was obvious that Glass wasn’t going to be the big consumer hit that they had hoped for. They started exploring other use cases for the product.

Astro Teller pointed out:

“When we originally built Glass, the work we did on the technology front was very strong, and starting the Explorer program was the right thing to do to learn about how people used the product….Where we got a little off track was trying to jump all the way to the consumer applications….We got more than a little off track.”

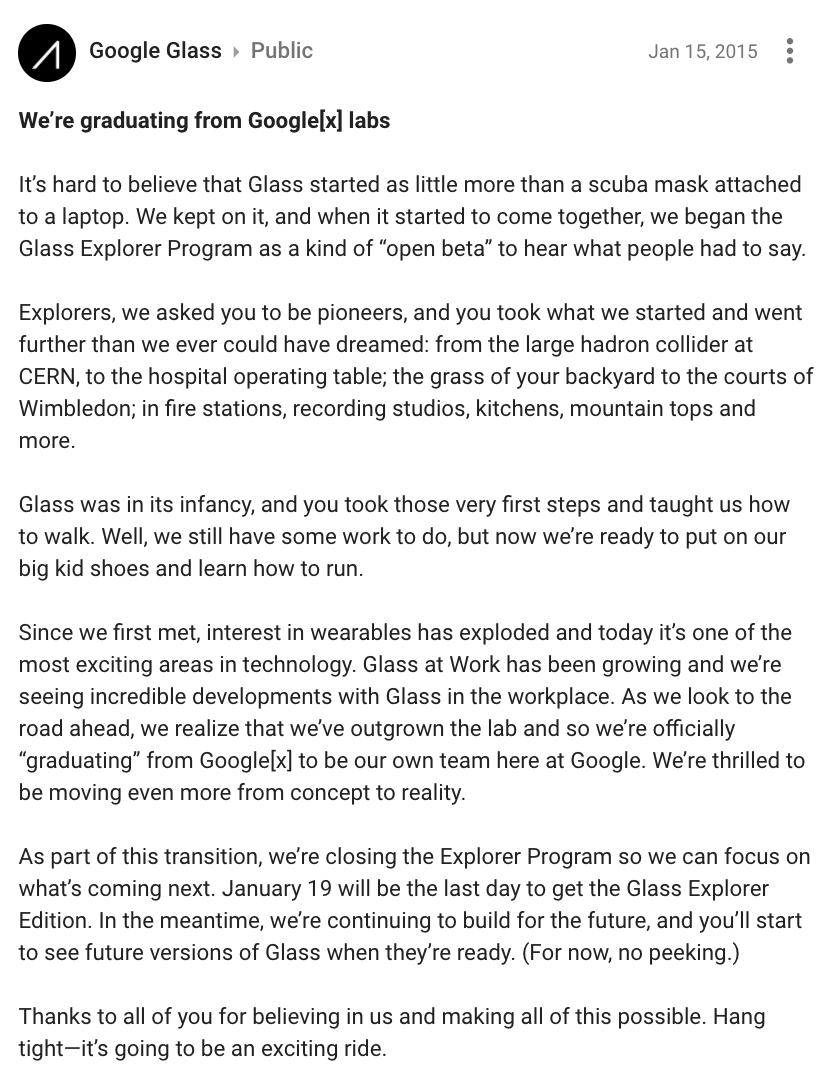

By January 2015, Google had withdrawn the consumer version of Glass. Google learned its lesson from launching too early, with too much hype. Just as they were winding down the consumer version of Glass, they launched a new enterprise initiative for the product.

To the public, Glass was a failed product that no one wanted. To Google, Glass was entering a new chapter.

2015-2017: The Relaunch

Back in 2014, just as Glass seemed doomed, a ray of hope appeared for the project. The team noticed that small startups had been purchasing pairs of Glass via the Explorers program, and building custom software on top of it for the enterprise. They were using Glass to do work in various industries—from manufacturing to healthcare.

The corporate interest in Glass was so promising that Google created a specific Glass for Enterprise team to help develop the new ecosystem.

This decision culminated in the relaunch of Glass this July—this time, positioned clearly as an enterprise tool.

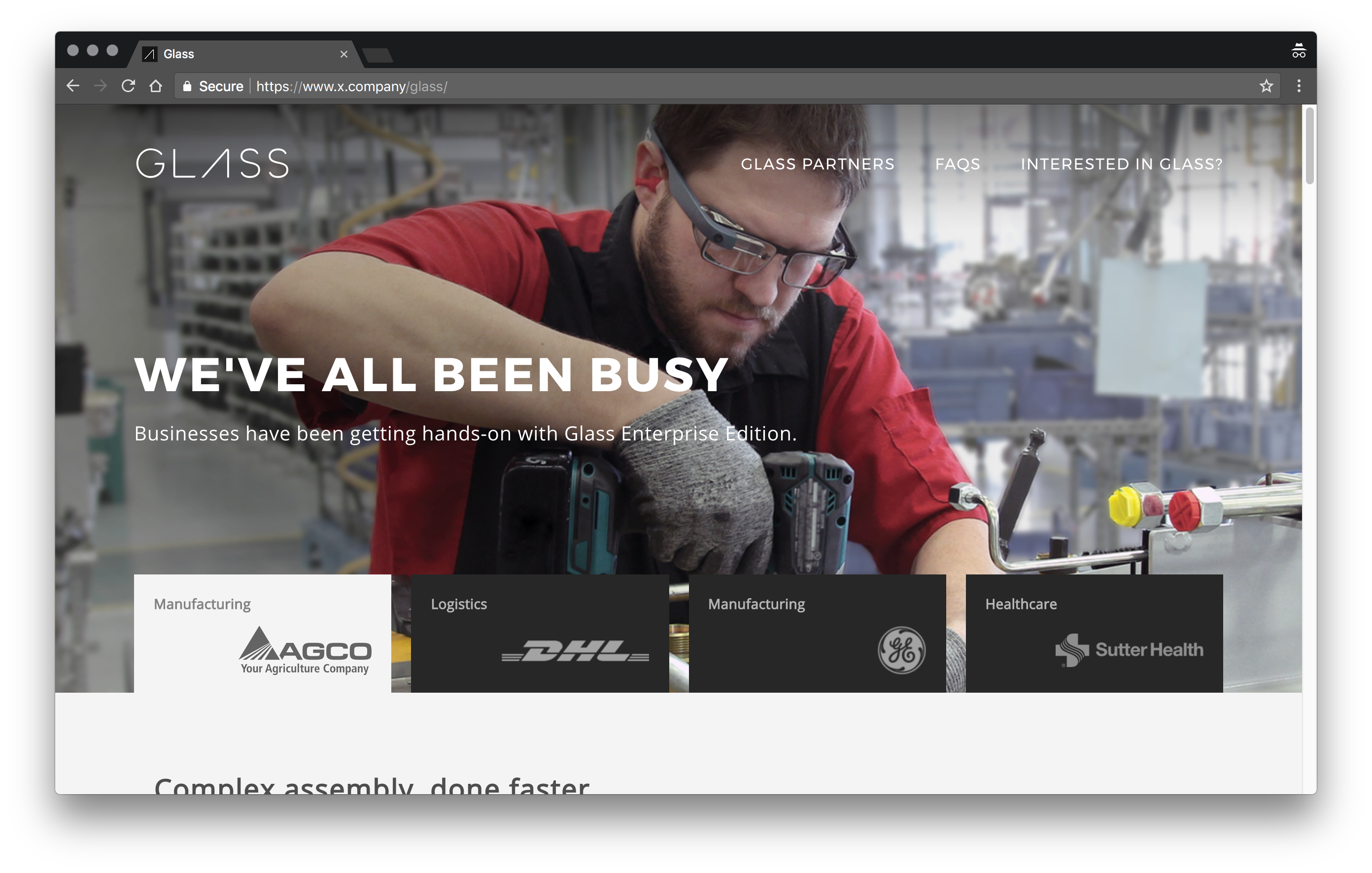

Where Glass’ consumer launch had splashed across magazine covers and the fashion runway, the new Glass landing page shows a factory worker wearing Glass while working with power tools. The product description includes clear use cases for Glass, from watching training videos and accessing instruction manuals to activating applications while working. Cementing the product’s new business positioning are testimonials from partners: “25% reduction on low volume complex assemblies.”

Where Glass’ consumer launch had splashed across magazine covers and the fashion runway, the new Glass landing page shows a factory worker wearing Glass while working with power tools. The product description includes clear use cases for Glass, from watching training videos and accessing instruction manuals to activating applications while working. Cementing the product’s new business positioning are testimonials from partners: “25% reduction on low volume complex assemblies.”

These specific details and concrete applications for Glass present a stark contrast to its consumer launch. Google had clearly learned its lesson.

Let’s dig into the events that led Google to this point:

2015: Google closes the Explorers program, announcing that Glass is “graduating” from Google X to its own team within the company. Glass is placed under the leadership of former iPod creator Tony Fadell. The Glass team focuses on refreshing the product for enterprise applications, working closely with 10 partner companies who work on the software side.

2016: Google’s new enterprise edition modularizes the frame of Glass, making it easy to detach the electronics and display, and clip them onto a pair of safety glasses. They improved hardware features like battery life, processing speed, and WiFi connectivity. Augmedix, a startup developing Glass applications for the healthcare industry, raises $17M.

2017: Google publicly announces the launch of Glass for Enterprise.

Back in 2014, as the consumer version of Glass was being thrashed, Google started partnering with companies like Boeing and GE to figure out what specific pain points Glass might help them solve.

“We talked to all of our Explorers and we realized that the enterprise space had a lot of legs,” says Jay Kothari, who is now project lead on the Glass enterprise team. Interest from corporations suggested that a dedicated team might work on a specialized version of Glass to serve them.

Placing Glass under the supervision of Tony Fadell and moving the product from the “moonshot factory” signaled Google’s belief in the product’s viability. Faddell commented at the time, “I remember what it was like when we did the iPod and the iPhone. I think this can be that important, but it’s going to take time to get it right.” The company went on a hiring spree, recruiting former developers and hardware engineers from Amazon to build the team out.

Keeping the project under wraps, the team worked with partners and enterprise companies to develop practical applications for Glass.

At AGCO, a manufacturer of agricultural equipment, factory workers use Google Glass to view instructions and checklists as they assemble complex machinery. AGCO estimates that Glass has helped reduce production time by 25%. At DHL, workers use Glass to scan items on racks and see what bins to place them in to fulfill orders—with an estimated 15% increase to efficiency. Meanwhile, at Dignity Health, doctors use Glass during patient examinations. Instead of logging information on a computer during the exam, information is recorded from a doctor’s Glass, transcribed, and processed.

Everything that made Glass feel invasive for consumers was no longer relevant in an enterprise setting. On the factory floor or in a doctor’s office, Glass was no longer a high-end gadget for taking pictures of family and friends. It was a tool engineered for getting work done. Workers use Glass to scan parts, access training videos, and record defects.

The kicker is that by working closely with partner companies and corporations, Google is finally putting together a healthy ecosystem with platform potential for Glass. The partner companies develop end-to-end solutions for Glass in specific verticals like healthcare, logistics, and manufacturing. They distribute those solutions directly to enterprise companies, driving higher usage of Glass. That gives Google specific customer feedback it can use to improve product.

Glass for Enterprise looks like it has the platform potential that Google originally intended for Glass, but in an enterprise setting. Over the past seven years, Glass has had a bumpy ride. Today, it finally seems to be finding its way.

Where Glass Can Go from Here

With the relaunched enterprise edition, Glass is finally starting to realize the high hopes around the product. Instead of trying to make Glass something that people wear all day, Google has taken the opposite approach. The enterprise edition of Glass has been designed and marketed to solve concrete, practical problems. In doing so, Google is overcoming the disaster of Glass’ early launch and opening new doors for the product.

With its renewed focus, Glass has a lot of room to expand.

- Increased modularization: While the consumer version of Glass was meant to be used by most people in the same way, the enterprise edition was designed for more flexibility. The enterprise edition modularized the frame, electronic display, and camera glass, allowing a worker to detach Glass from the frame and stick it on a pair of safety glasses. In the future, Google could double down on this approach. They could allow third parties to create specialized modules for Glass, like an infrared camera for doctors, or external memory chips. This increased flexibility would make Glass adoption easier across a broader set of industries.

- Back to consumer: Snapchat’s Spectacles have shown that the consumer market is receptive to wearable smart glasses—as long as they are packaged in the right way. By simplifying the enterprise edition into an initial consumer version, Google would be able to offer consumers a lower and more palatable price point. The enterprise edition takes a step toward addressing privacy concerns by shining a light when Glass’ camera is activated. Most importantly, they need to nail their value proposition and show people what Glass can do that their smartphones can’t.

- Platform potential: The consumer version of Glass alienated developers, who couldn’t charge for their applications or make money through ads. With the enterprise edition, developers are building new applications for Glass and making money by selling the hardware and software to corporations, creating a profitable ecosystem. Meanwhile, the Glass team is partnering with Google Cloud to take the product further. That certainly seems to be a step in the right direction. As a product, Glass is positioned to benefit from Google’s deep expertise in cloud computing and machine learning.

While Glass has been around for seven years, in many ways the product’s relaunch this year signals a new beginning. There are a ton of ways that Google could expand and grow the product. That’s actually the difficulty of creating a product like Glass in the first place. More than anything, Google’s ability to execute methodically will determine the success or failure of the product.

3 Key Lessons Learned From Google Glass

Building any product is a constant process of experimentation, failure, and learning. That’s even more true for a product as ambitious as Google Glass.

While Glass appears to have successfully reinvented itself, there are a lot of points in its timeline where choosing a different path could have saved the team headaches and time. If you’re building a product today, these are the key lessons to take away from the story of Google Glass:

1. What’s the goal of your product?

This is a crucial question to answer when you’re trying to build a brand new platform, or an application on a new technology platform. Where did the idea come from? How have you validated the idea? How do you know whether building it is a risk worth taking?

To create a product that people will love, you have to validate your idea first.

- Create a problem-hypothesis that describes your target customer and the problem that you think they have. This should take the form of: [Group of people] have a problem [their problem].

- Set up a system that pulls users who fall into your target audience toward your idea for solving the problem. For a new product or idea, you can create a mock landing page that explains your idea and includes a sign up form where interested visitors can give you their email addresses.

- The last step is to survey people who sign up to learn more and further validate your idea. Ask them what existing products they’re using, how often they use them, and what their key pain points are around the products they use.

2. Run user research and tests before, during, and immediately after initial product development.

It’s particularly important for revolutionary new products to launch gradually, starting in one or two small test markets first. If you’re working on a new and groundbreaking technology, chances are that you’re already a believer. That’s why it’s so important to get outside of your own head and into how end-users will think, feel, and react to the product. It’s not enough to have a vision. That vision has to be something that your customers can relate to.

Here are a couple of resources that will help you run better user research:

- Stop Ignoring your Competitors and Do Competitor Analysis Instead

- Everyone Forgets Technical Research

- How to Create Early Access Surveys for a New Product or Feature

- How to Build a UX Research System that Runs on Autopilot

3. Nail the value proposition

Make it very clear why the product you’re launching is something your customers should be interested in. How does this product differ from competitors’ products? If there are no major competitors, talk about how the product solves a problem (for whom, when, and how). What are the most powerful use cases for the product? Why should anyone care?

One exercise that will help you achieve this is writing a press release or blog post before you get started shipping code. It’s a technique developed by Amazon, where every product initiative begins with a press release. That helps Amazon “work backwards” around customer needs.

Former Amazon PM Ian McAllister put together this outline that you can use to get started.

Heading: Name the product in a way the reader (i.e. your target customers) will understand.

Sub-Heading: Describe who the market for the product is and what benefit they get. Keep it to one sentence only underneath the title.

Summary: Give a summary of the product and the benefit. Assume the reader will not read anything else, so make this paragraph good.

Problem: Describe the problem your product solves.

Solution: Describe how your product elegantly solves the problem.

Quote from You: A quote from a spokesperson in your company.

How to Get Started: Describe how easy it is to get started.

Customer Quote: Provide a quote from a hypothetical customer that describes how they experienced the benefit.

Closing and Call to Action: Wrap it up and give pointers on where the reader should go next.

Back in 2014, Astro Teller wrote a piece for CNN that explained the inspiration behind Glass:

“When a technology reaches this point of invisibility, it has reached its ultimate goal: becoming part of our routine, with no compromise between us and the technology….What inspired Google Glass was partly the realization that consumer technology products often don’t live up to those standards.”

I love this. Technology shouldn’t call attention itself. It’s a means to an end. That end is to give people a better way of doing things that they’re already doing. All of Glass’ early problems can be traced back to forgetting this core principle. With the best engineers in the world and nearly unlimited resources, Google grew overconfident and distracted from what they should have been doing all along—helping people solve problems.

By launching too early and with too much hype, Glass didn’t allow itself to become invisible. Instead the product itself became the focus of everyone’s attention. It’s a lesson that Google has since learned from and is applying to the enterprise edition of Glass.

If you only remember one thing after reading this article, remember that the best products don’t come from the technology behind them. They’re about how well they become a part of our lives.