Is Snapchat Going to Die?

By 2011, Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn had effectively dominated the social media space so completely, it felt like there wasn’t room for another social app. However, to Evan Spiegel, then a product design student at Stanford, most social media services lacked a way for friends to communicate privately. They had created unprecedented opportunities to share and connect but lacked the intimacy of real-world interactions.

This was how the idea for Snapchat was born.

Since its origins in 2011, Snapchat has grown and evolved to become one of the most popular social media platforms in the world. However, going public and fending off increasing competition from Instagram have stalled Snapchat’s growth and the company’s next move.

Here are a few things I cover in this article:

- How Snapchat cleverly leveraged existing behaviors among young people to create a novel, unique product

- How Snapchat actively encouraged users to create new, fun, and exciting content

- Why Snapchat’s unique approach to sharing emphasized authenticity

To understand Snapchat’s growth, we need to start by looking at what prompted Spiegel to develop his idea in the first place.

2011-2013: Capturing Real-World Behavior

Although Evan Spiegel is often credited as the creator of Snapchat, it was actually Spiegel’s Stanford classmate, Reggie Brown, who originally came up with the idea for the app. Brown approached Spiegel with his idea in April 2011 due to Spiegel’s business experience. Brown and Spiegel asked another classmate, Bobby Murphy, to help them code the prototype of their application, which they named Picaboo. The trio launched Picaboo on the iOS App Store in July 2011.

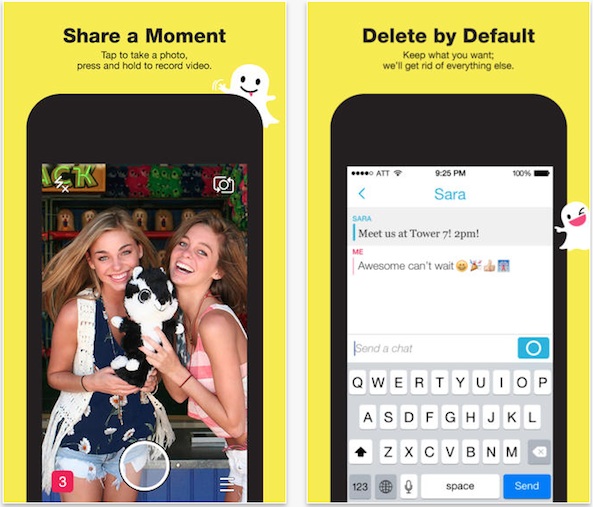

Brown’s original vision was a social app that allowed users to send pictures to one another, which would be automatically deleted after a certain period of time. This was a radical concept at the time. Sharing intimate details of our lives on feeds that are preserved forever isn’t how we communicate in the real world. Unlike privacy-minded messaging apps that came later, Snapchat’s unique, disappearing images were an attempt to get closer to the actual experience of interacting with another human being. The conversations we have with one another aren’t permanently archived, like the vast majority of posts on social media platforms. They ultimately fade and disappear from our memories. Snapchat’s ephemeral picture messages aimed to capture this experience.

This novel approach was clever, but Spiegel and his co-founders wanted to re-create another aspect of the real world with Picaboo—passing notes between friends in class. For generations, schoolchildren have quietly passed secret notes between themselves to avoid arousing the suspicions of stern teachers. Snapchat wanted to leverage this familiar behavior as a core part of the experience. This was incredibly smart. Not only did this directly appeal to the younger userbase Snapchat wanted to attract, it lowered the barrier to the app’s “eureka” moment. This was a crucial aspect of Snapchat’s onboarding UX that helped propel the app to insane heights of growth very early on.

Shortly after Picaboo’s release, Spiegel, Brown, and Murphy received a cease-and-desist letter from a company that had already claimed the name Picaboo. However, their app’s emerging identity crisis wasn’t the only problem they encountered. Snapchat’s earliest incarnations allowed users to take screenshots of their messages with their iPhones’ built-in screengrab function. This defeated the purpose of Snapchat’s ephemeral messaging completely. In September 2011, Spiegel and company decided to rebrand their app, and Snapchat was officially born. They also introduced a feature that notified users if the recipient of a message had taken a screenshot.

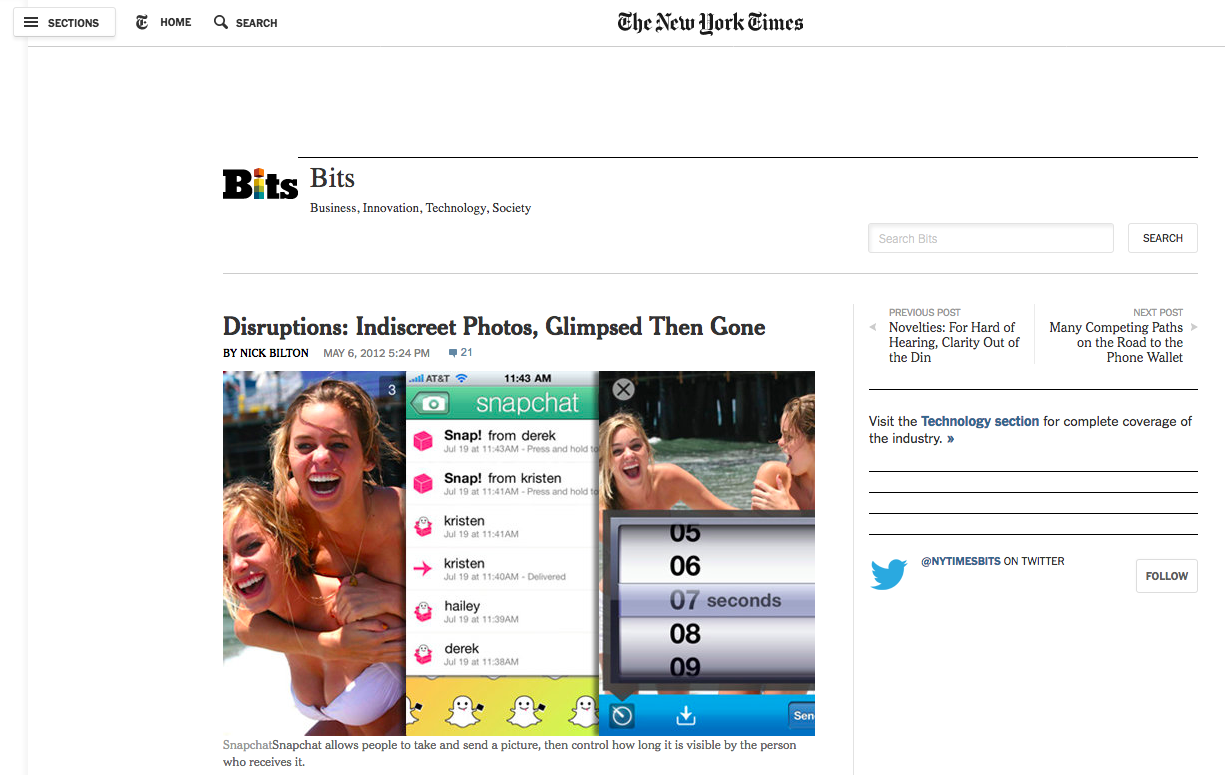

Despite the novelty and potential of Snapchat, early user growth was sluggish. With little marketing budget to speak of, Snapchat grew primarily through word-of-mouth for the first year. That all changed in May 2012, when Nick Bilton, then a writer for The New York Times, wrote about Snapchat. However, while Bilton missed the point of Snapchat, the profile in the Times did wonders for Snapchat’s publicity.

On May 9, 2012, Spiegel published Snapchat’s first blog post.

“Snapchat isn’t about capturing the traditional Kodak moment. It’s about communicating with the full range of human emotion—not just what appears to be pretty or perfect.” — Evan Spiegel, co-founder, Snapchat

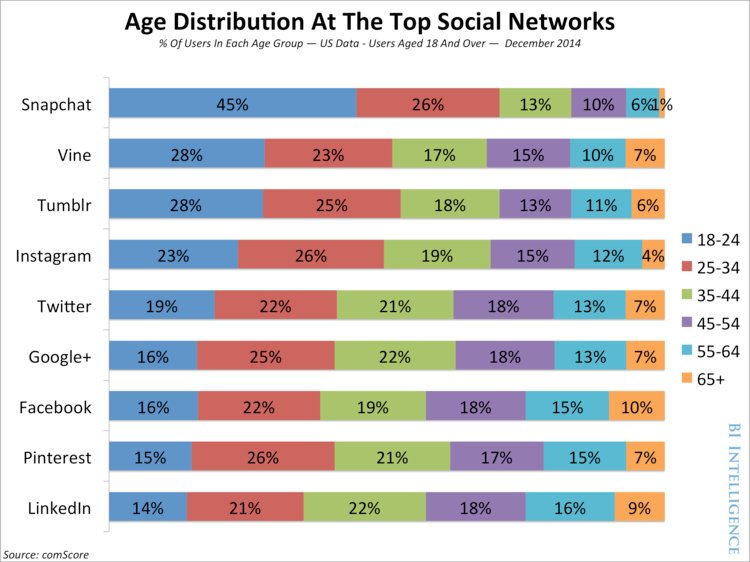

Later that month, Snapchat raised an incredible seed round of $485,000 led by Lightspeed Ventures. At the time, Snapchat had fewer than 100,000 users. Aside from the profile in the Times, press had been scarce. In short, there was virtually nothing to support the kind of seed round that Snapchat managed to raise—except the recommendation of a teenage girl. Jeremy Liew, a partner at Lightspeed, had seen Snapchat but hadn’t been particularly impressed with the app or its traction. That changed when Liew’s VC partner, Barry Eggers, told Liew that his teenage daughter had vouched for Snapchat’s low-key popularity. Eggers’ daughter had said that, alongside Angry Birds and Instagram, Snapchat was the must-have app.

Interestingly, Snapchat’s early growth trajectory looked a lot like that of Facebook. Although the profile in The New York Times had given Snapchat some much-needed publicity, much of Snapchat’s early growth had been driven by word-of-mouth among high-school students across southern California. However, another factor in Snapchat’s rapid growth during early 2012 that most people overlook was the dramatic uptick in smartphone ownership among this younger demographic.

In Q4 2011, Apple reported a 121% year-over-year increase in iPhone sales, many of which were given as gifts during the holidays. For many younger iPhone owners, this was the first time they had a smartphone with a front-facing camera, allowing them to take selfies. The timing couldn’t have been better for Snapchat, and the combination of these factors drove enormous organic growth.

Liew noticed that, although Snapchat’s userbase was small, its engagement metrics were incredible. The app was proving incredibly sticky, and many users were much more engaged with Snapchat than they were even with Facebook. Snapchat had stumbled upon something incredible. Users were sending more messages and engaging with the app for longer because of the ephemeral nature of the app. This is what made Snapchat so unique in an already crowded space.

This was enough for Liew. Lightspeed invested almost half a million dollars in Spiegel’s company.

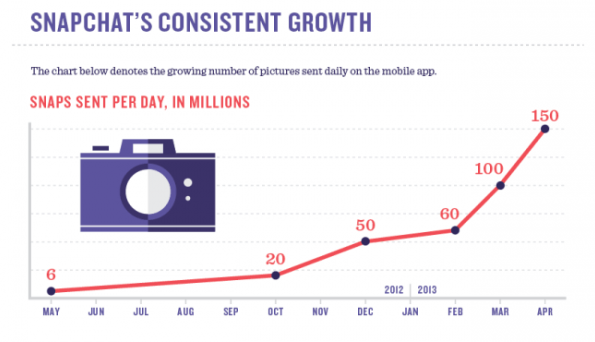

In October 2012, five months after its seed round, Snapchat launched its Android app. This gave Snapchat even more momentum. The app’s small but highly engaged userbase had grown considerably. By the time Snapchat launched its Android app, Snapchat users were sending more than 20M snaps per day.

However, until that point, Snapchat had been fairly static from a product development perspective. Aside from the addition of the screenshot notification feature, there had been no major changes made to Snapchat as a product. That changed in December 2012, when Snapchat gave users the ability to record 10-second videos and share them with their contacts. This was another smart move, given the rapidly growing popularity of video-sharing service Vine at that time, which Twitter reportedly acquired in October 2012 for $30M before Vine’s official launch.

The addition of short videos to Snapchat was a clever strategic move, but Snap also nailed how it integrated the feature into the app. Rather than forcing users to switch between photo and video modes on their mobile devices, all users had to do to shoot video was hold down the image-capture button to send a video message instantaneously. This seamless method of switching between the two shooting modes is an excellent example of how Snapchat kept its users in mind as the product developed and focused relentlessly on reducing friction.

“To get a better sense of how people were using Snapchat and what we could do to make it better, we reached out to some of our users. We were thrilled to hear that most of them were high school students who were using Snapchat as a new way to pass notes in class—behind-the-back photos of teachers and funny faces were sent back and forth throughout the day. — Evan Spiegel, co-founder, Snapchat

This idea of ephemeral messages was foundational to the experience of Snapchat as a product. However, what was truly brilliant is that Snapchat successfully capitalized on the age-old behavior of schoolchildren passing secret notes between one another in class. This is an excellent example of how making existing behaviors easier with technology can be such a powerful differentiator, even in intensely competitive markets such as social media.

Another aspect of Snapchat that was incredibly compelling was how well it reduced the friction in sharing social updates. Unlike platforms like Facebook and Twitter, Snapchat’s ephemeral messaging significantly reduced the apprehension that often accompanies posting updates online. Secure in the knowledge that their updates would soon disappear forever, Snapchat users were much more likely to share updates without worrying about their permanence and also share more genuine, authentic updates about themselves and their lives. These two factors changed the way that millions of younger people saw and interacted with social media and helped propel Snapchat to amazing heights growth-wise.

By early 2013, Snapchat had become the hot property in social. Snapchat raised $13.5M as part of its Series A round, led by Benchmark’s Mitch Lasky in February 2013, giving it a valuation of between $60M-70M. By this point, Snapchat was growing amazingly quickly. Snapchat users were sending more than 60M snaps per day and more than 5B snaps in total. Incredibly, Snapchat was still being run by a skeleton crew of just five full-time employees. Shortly after raising its Series A, Snapchat hired an additional five people, bringing the company’s total workforce to a grand total of just 10 people.

Snapchat continued to grow throughout 2013. By June, Snapchat users were sending more than 200M snaps every day—an increase of 150% in just six months. That month, Snapchat raised another $100M as part of its Series B round of $80M, led by Institutional Venture Partners, plus an additional $20M raised through a secondary market round when Spiegel and Bobby Murphy sold some of their personal shares in the company.

However, despite having raised a considerable sum in venture funding, Spiegel had apparently given little thought to monetization. In an interview with Fortune, Spiegel mentioned his admiration for Chinese multinational investment conglomerate Tencent, noting that in-app purchases were driving the vast majority of Tencent’s revenues. For the time being, at least, Spiegel was focused intently on the product.

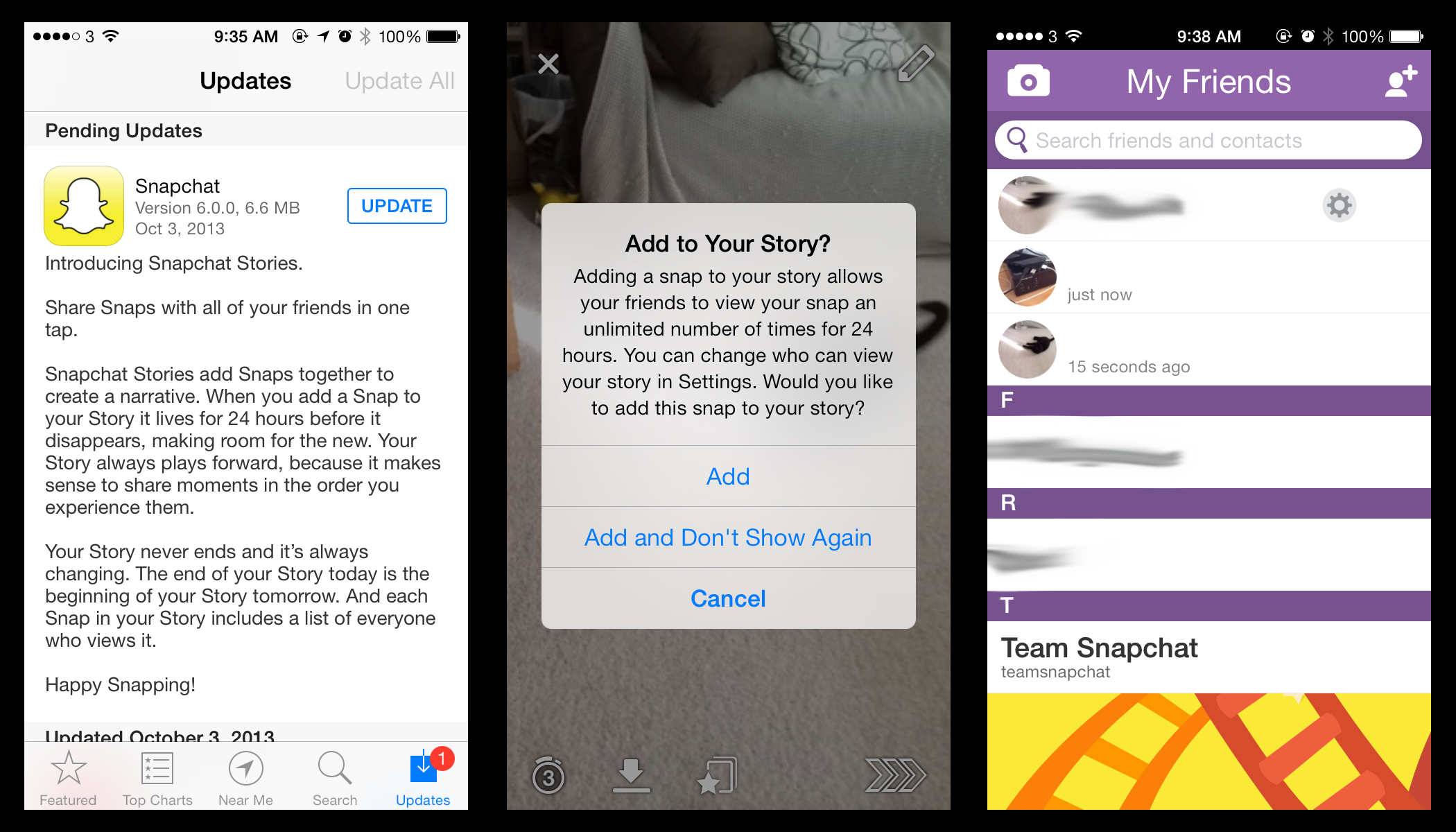

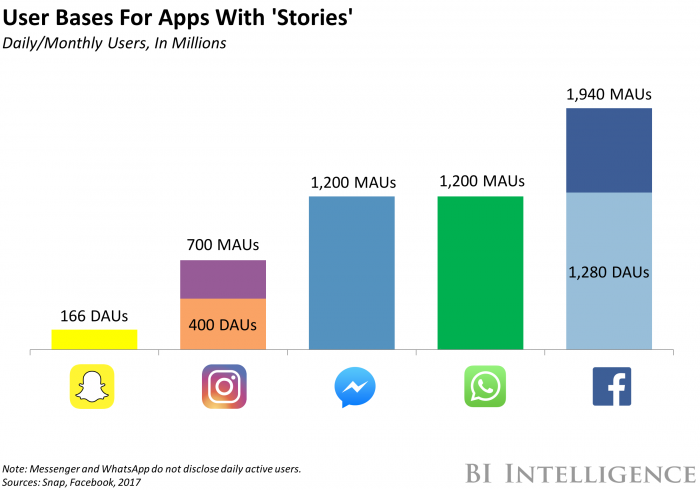

In October 2013, Snapchat introduced Stories. This was arguably the most important—and influential—update that Snapchat ever made to the product. Stories allowed users to create montages of snaps that would remain available for 24 hours. Users could still decorate their snaps with Snapchat’s ever-growing range of images, illustrations, captions, and animated gifs, but they could now combine several snaps into a single, sequential “story.” This was a huge moment for Snapchat as a company and as a product. Everything about Stories—how it looked, how it worked, how it felt, even the name—was genuinely new and exciting.

Snapchat closed out 2013 by raising $50M in its Series C round led by Coatue Management. At the time, the Silicon Valley rumor mill had shifted into high gear with speculation that Snapchat had hoped to secure $200M of additional funding from Tencent. Although these rumors turned out to be false, Snapchat had raised a total of more than $123M in venture funding despite having no clear plans in terms of monetization. What the company did have, however, was a userbase of more than 30M daily active users who were posting upward of 400M snaps per day—even more than the number of photos uploaded daily to Facebook.

By this point, Facebook had been watching Snapchat carefully, sensing the threat the growing company posed. To preempt this threat, Facebook made a secretive offer to acquire Snapchat for $3B in November 2013. Both Spiegel and Brown would have personally pocketed at least $750M each had they accepted Facebook’s offer. However, contrary to some reports at the time, Spiegel didn’t reject Facebook’s offer because the price wasn’t right. Spiegel turned Facebook down because, by offering such a high price, the company had inadvertently revealed a potentially critical vulnerability in Facebook’s strategy at that time—namely, the comparative weakness of Facebook Messenger, which had been released only a few months previously.

Despite its lack of a solid monetization strategy, Snapchat’s explosive growth and remarkable popularity among a primarily younger userbase made the company a very attractive proposition to investors. By the end of 2013, Snapchat had become the new social media platform—and it was poised to achieve even greater heights in the coming years.

2014-2016: Camera, Communication, Content

Despite having a small team, Snapchat had grown incredibly quickly in just two years. The company had focused intently on developing the product organically while experimenting with ways it could monetize without interrupting the user experience. The introduction of Stories at the apex of its early growth further established Snapchat as a serious player in the social space, and the company would spend much of the next two years developing new product features.

May 2014 saw the next major update to Snapchat as a product, Chat. This feature wasn’t as impactful as Stories had been, but it was still a necessary and logical addition to the product. Users could swipe right on a contact’s name in their Snapchat inbox to open a private, direct-message channel with that contact. Similarly to snaps, all information would disappear when users were finished with their conversation.

The next major product update came shortly after the launch of Chat. Our Story was introduced in June 2014 and allowed users to contribute images and video to public feeds of live events. This was clever in two ways:

- It brought a much-needed collaborative element to Snapchat as a product, allowing many users to contribute to a single feed from an event.

- As the precursor to Discover, Our Story gave Snapchat the opportunity to test its product hypothesis that users would come to Snapchat to consume content, not just message their friends.

In July, Snapchat introduced Geofilters. This feature allowed users to create content using filters that were only visible when Snapchat users were within specified locations. For example, Snapchat users visiting Disneyland—which featured prominently in Snapchat’s promotional videos announcing the feature—were able to access filters and other elements that were only available within the confines of the world-famous theme park. This also laid the foundations for Snapchat’s monetization efforts later on.

After months of product iteration, Snapchat was finally ready to begin experimenting with monetization. In October 2014, Snapchat introduced the first advertisement on the platform, a short video promoting the horror movie Ouija. Snapchat went about introducing ads in a very clever way. First, the ads were introduced as a feature within Stories, which helped the promotional content blend in with the content users were well-accustomed to seeing and avoided the jarring, disruptive advertising experience disliked by many users. Second, the ads were opt-in, meaning they weren’t forced on users without their consent. Snapchat went to huge lengths to make its ads feel native to the flow of the app rather than an interruptive experience. Above all else, the product had to remain cohesive.

The following month, in November, Snapchat partnered with mobile payments provider Square to offer the second of its monetization efforts, Snapcash. The feature looked and felt incredibly similar to Square’s own Cash app and was even created by the same team as Square’s Cash app. Like the Square product that inspired it, Snapcash was ultimately short-lived. It did, however, prove that Snapchat was willing to iterate and experiment, even as the company grew.

December 2014 saw the release of Community Geofilters. An extension of Snapchat’s existing Geofilters feature, Community Geofilters allowed any Snapchat user to create custom geofilters for public spaces. Although Community Geofilters was essentially just an expansion of an existing feature, it was a small but important addition in terms of the “social” aspects of Snapchat as a platform. Geofilters had been popular with Snapchat’s user base, but allowing users to create their own in shared public spaces was a great way to encourage and facilitate engagement across the platform and allow users to create even more personalized content.

Shortly after the launch of Community Geofilters, Snapchat announced it had raised $485M as part of its Series D round led by Kleiner Perkins. At the time, there was a great deal of confusion surrounding the terms of the deal. Initial reports suggested that Snapchat had intended to raise $40M in its Series D round. However, intense demand soon prompted Snapchat to aim for a slightly more ambitious figure—$900M. (And no, that’s not a typo.) Realizing this might have been a little too ambitious, the company scaled back to a more modest $500M. That gave Snapchat a valuation of at least $10B.

Despite having raised Herculean amounts of venture funding in just three years, Snapchat desperately needed the cash. According to TechCrunch, Snapchat’s burn rate was more than $30M per year, roughly half of which was being spent on image hosting with Google App Engine. Another source told TechCrunch that Snapchat was spending more than $3M per month on legal fees alone, having been the target of several lawsuits during its short lifespan.

By early 2015, monetization had become a much more urgent priority for Snapchat. In January 2015, Snapchat announced its next major product update, Discover. Aside from Stories, the launch of Discover is among the biggest and boldest features implemented by Snapchat to date. Discover allowed users to see content from some of the world’s leading media brands. Discover launched with 11 media partners including BuzzFeed, CNN, ESPN, The Food Network, National Geographic, and VICE.

Discover was brilliant in two ways:

- It gave media brands unprecedented access to Snapchat’s primarily young (and immensely lucrative) audience and allowed brands to create sponsored content that was on-brand and aligned closely with the Snapchat experience—a rare win-win for advertising partners and users.

- It allowed Snapchat to pursue multimillion-dollar media partnership deals with some of the world’s leading entertainment brands rather than exclusively chasing smaller ad revenues from traditional digital advertising sales.

“Discover is different because it has been built for creatives. All too often, artists are forced to accommodate new technologies in order to distribute their work. This time we built the technology to serve the art.”

Two months after the launch of Discover, Snapchat raised another $200M in its Series E round led by Chinese e-commerce titan, Alibaba. This round gave Spiegel’s company a valuation of approximately $15B, making it the third-most valuable venture-funded company in the world, second only to Uber, valued at $40B at that time, and Chinese electronics manufacturer Xiaomi, valued at $45B at that time. The company’s Series E round brought Snapchat’s total venture funding to almost $650M, an absolutely incredible figure for a four-year-old company. Snapchat’s strong user growth and even stronger engagement metrics were attractive to investors, but the company’s monstrous Series E round also reflected broader trends in venture funding. 2014 saw the highest levels of venture funding investment since 2001, with almost $48B invested that year alone—a 62% year-over-year increase from 2013.

Snapchat continued to grow and iterate on its monetization strategy throughout 2015. By May 2015, Snapchat finally cleared the 100M DAU threshold, and more than 400M snaps were being sent across the platform every day. In June, the first Sponsored Geofilters were introduced. The first corporate sponsor to experiment with Sponsored Geofilters was McDonald’s. The first two digital stickers introduced as part of the Sponsored Geofilters rollout were an illustration of a double cheeseburger and an animated gif of french fries falling from the top of the screen to the bottom. Granted, this might not have been the most exciting use case for a new product feature, but it did highlight the commercial potential of Sponsored Geofilters, something the company would pursue aggressively in the future. Alongside McDonald’s, General Electric and Ted, the movie, also signed on as Sponsored Geofilters partners shortly after the feature was announced.

September 2015 saw the release of Snapchat’s latest monetization experiment, Lenses. These filters were Snapchat’s first foray into the world of in-app purchases and let users add animated effects to selfies taken in Snapchat. The first Lenses were immediately popular with users and let them vomit rainbows, replace their eyes with bulging hearts like something out of a Wile E. Coyote cartoon, and even transform into hideous, nightmarish monsters.

The Lenses themselves were available for free—a smart move for a company still testing the murky waters of microtransactions—but the real genius of Snapchat’s monetization strategy with Lenses was the option for users to pay a small amount to watch a limited number of replays. Users ordinarily got one free Replay per day. When Lenses launched, users could opt to pay 99 cents for three additional Replays, $2.99 for 10 Replays, and $4.99 for 20 Replays.

This was incredibly smart. Not only did Snapchat offer users an entirely new and fun experience to play with for free, thus avoiding the potential negativity of becoming a “pay to play” app by gating premium functionality behind paywalls, it also introduced an entirely new revenue stream that would finally leverage Snapchat’s immense userbase. However, despite the potential of Snapchat’s microtransactions, the company discontinued its paid Replays just a few months after they were introduced, presumably due to low traction.

After 2015’s rapid-fire product updates, Snapchat made few changes to the product after the launch of Lenses. The next major launch came in March 2016 when Snapchat debuted the second iteration of Chat. Snapchat’s “Chat 2.0” wasn’t worlds apart from the product’s existing Chat function except that it allowed users to start chat conversations and transition to video or audio chat seamlessly when the other person joined the chat. The idea was to mimic how we converse in real life and make Chat feel as close to the experience of real-world interactions as possible.

Alongside Chat 2.0, Snapchat also introduced its autoplay feature for Stories, which lets users watch a continual stream of Stories one after another without the need to manually select which Stories to play, as well as On-Demand Geofilters for private events. Like Replays, On-Demand Geofilters were initially priced at $5, creating yet another microtransaction revenue stream.

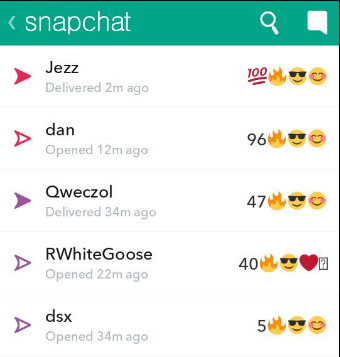

The biggest product update of 2016, however, came in March with the release of Snapstreaks. Essentially a running counter of how many consecutive days two Snapchat users had messaged one another, Snapstreaks was a clever gamification strategy that added a layer of compulsive behavior to an already sticky app. If users messaged each other at least once in a 24-hour period for a minimum of two consecutive days, those users would see a fire emoji displayed next to their name. If they kept the snapstreak going, the fire emoji would be displayed with a number representing how long that snapstreak had been. It didn’t add much in terms of functionality, but it did make Snapchat even more compelling for power users.

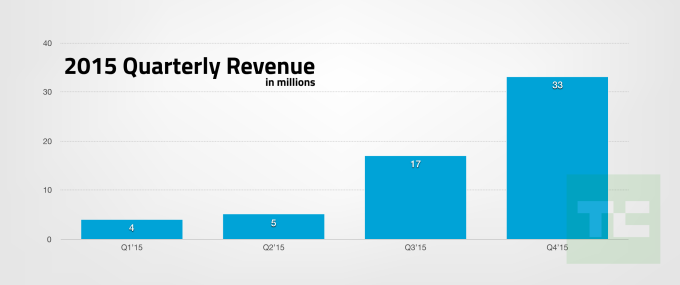

In May 2016, Snapchat raised $1.8B as part of its Series F round for a valuation of approximately $20B. Although much of the industry press was preoccupied with what Snapchat planned to do with its latest truckload of cash, the announcement was overshadowed by the leak of a pitch deck for prospective investors. The deck revealed that Snapchat had made just $59M in revenue in 2015. This was lower than many analysts had expected, but it wasn’t entirely surprising given the company only began to monetize in earnest toward the end of 2015. What was of concern, however, were the revenue forecasts in the pitch deck.

Snapchat estimated that, based on the revenue figures above, revenues for 2016 would be between $250M-350M, and that revenues for 2017 would be as much as $1B. However, these estimates were not made on Snapchat’s internal data but rather the company’s optimistic sales targets. Nor did they factor in revenue streams such as Discover or advertising placement.

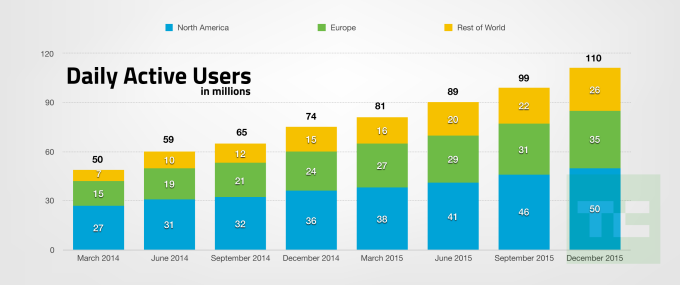

The leaked deck wasn’t all bad news, however. As of December 2015, Snapchat had more than 110M DAUs, an increase of almost 50% from the 74M DAUs reported in December 2014:

Snapchat announced the launch of Memories in July 2016. The feature, which allowed users to save snaps for later viewing and editing, was met with both excitement and apprehension. Allowing users to save certain content was a logical move and played to Snapchat’s strengths in capturing real-world behavior. Despite the ephemeral nature of Snapchat as a platform, it made sense to give users a way to revisit old updates in much the same way we use photo albums and personal timelines on Facebook.

In August 2016, competition in the social space began to intensify. Instagram announced its own version of Stories, while Facebook launched its own range of digital stickers and filters for its photo app. There was little mystery about the inspiration for these products, but that wasn’t the point. Snapchat had proven extremely sticky due to the ephemeral nature of its messages. Users were checking in with the app multiple times every day and engaging for longer. Conversely, engagement with Instagram and Facebook’s permanent feeds was stagnating, so Instagram did what it had to do—it cloned Stories into its own product.

Snapchat announced a major rebrand in September 2016. Snapchat would retain its name and brand identity as a product, but the parent company was renamed to the shorter, simpler Snap Inc.

By the end of 2016, Snapchat’s honeymoon period was largely over. Both Facebook and Instagram had incorporated elements formerly unique to Snapchat into their core properties, and although Snapchat was growing rapidly, it would face several difficult challenges in the coming years—not least of which was a major backlash against a radical overhaul of the service’s UI and the product’s emerging identity crisis.

2017-Present: Going Public and ‘Reinventing the Camera’

After several years of explosive growth, Snapchat was struggling. The features that had distinguished the product in a crowded space had been co-opted by Snap’s two biggest competitors, and the company appeared to have few ideas on how it could continue to differentiate itself. Snapchat had grown rapidly early on due to the strength of its product development. But by 2017, the company had not invested as much time or effort into the problem of lasting growth.

In March 2017, Snap Inc. went public on the New York Stock Exchange. Trading began at $24 per share—considerably higher than the $17 per share analysts had anticipated. This gave Snap Inc. a valuation of almost $30B. Snap’s surprisingly strong IPO revealed why Spiegel had been right to reject Mark Zuckerberg’s $3B acquisition offer in 2013. The 41% increase in Snap’s share price made it the largest tech IPO in three years.

However, despite investor confidence, Snap was in trouble. At the time of its IPO, Snap had approximately 161M DAUs, significantly fewer than Instagram (which had roughly 600M DAUs) and Facebook (which had almost 1.5B DAUs).

That wasn’t the only problem facing Snap. As well as struggling to compete in terms of users, Snap was also losing money. Despite dramatic increases in revenue, Snap lost approximately $515M in 2016—losses that would continue to mount in 2017.

“High valuation metrics in and of themselves does not necessarily make a poor investment. But by far the most critical characteristic for high multiple, high growth companies in our view is the sustainability of competitive advantage. And this is where we have long-term concerns for Snapchat because of the aggression of Facebook.” — Neil Campling, former Global Head of TMT Research, Northern Trust Capital Markets

Despite the serious problems facing Snap as a company, investors were bullish on Snap’s prospects as an investment vehicle. Not because of the product’s potential, but because there had been a drought of so-called “unicorn” companies that promised strong growth and potentially high ROI for investors.

After a strong IPO, Snap continued to grow, albeit much more slowly than it had in previous years. In November 2017, Snap unveiled a daring new redesign that fundamentally changed how the app looked, worked, and felt.

The new design was immediately and powerfully unpopular.

In a video explaining the rationale for the dramatic visual overhaul, Spiegel said that his company’s aim was to essentially separate “social” from “media” on Snap. Spiegel added that, while Facebook is ostensibly designed around the concept of communities, Snap wanted to emphasize individual relationships. However, regardless of Snap’s intentions, the actual execution of the redesign was handled very poorly. From a UX perspective, the new-look Snapchat was horribly confusing. The redesign had sandwiched Stories, one of the app’s most consistently popular features, between the app’s private messaging functions. This wasn’t just unintuitive; it was actively confusing to even long-time users.

That wasn’t the only cloud hanging over Snap. In a particularly damning story published by The Daily Beast, it was revealed that between April and September of 2017 Snap saw zero growth in the number of users posting Stories—an alarming revelation that was almost certainly driven by the popularity of Instagram and Facebook’s own Stories-like products. Snapchat’s userbase had grown by approximately 7% during that period, but it was painfully clear that Snap was in the midst of a full-blown crisis.

The Daily Beast’s report also cast doubt on Snap’s leadership. Several former Snap employees interviewed for the article described Spiegel as “paranoid” and claimed that only a tiny circle of trusted insiders on Snap’s executive team were aware of the product’s long-term strategy. Even more damaging were claims that Snap’s culture of secrecy also extended to advertising partners. The Daily Beast reported that Snap’s Discover publishers are given access to an analytics dashboard for their own channels. However, Discover advertising partners are not given DAU numbers for that part of the app. Snap was keen to promote Discover as a way to reach Snap’s 178M DAUs, but The Daily Beast reported that, according to its own internal analysis of Snap user data, only approximately 20% of Snap users consumed media from a Discover daily edition of a publication.

“I think fundamentally, if you look at the redesign, it’s really important to try and understand the problem that we were trying to solve. When we looked at social media, one of the biggest problems that really stood out to us was this constant conflict between needing to have a small group of friends to feel comfortable expressing yourself, but also needing to have a large group of friends so that you can watch more content.” — Evan Spiegel, co-founder, Snap

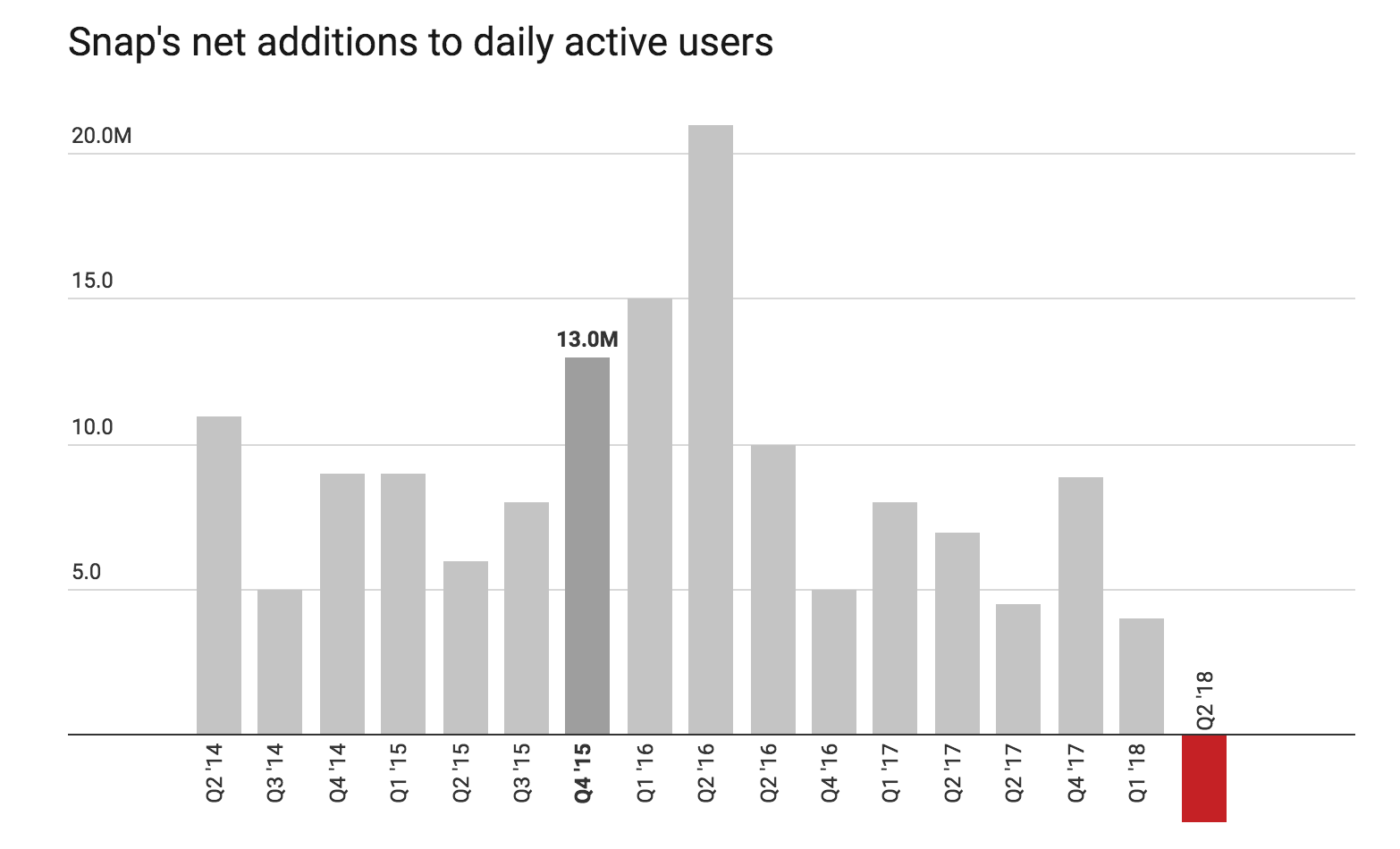

Spiegel was eager to reassure investors and users about the intentions behind the redesign, but the damage had been done. Between Q4 of 2017 and Q1 of 2018, Snap’s DAU figures more than halved, from 8.9M in Q4 2017 to just 4M in Q1 of 2018. Even more worrisome for Snap was the fact that not only had its overall DAU volume fallen, it had done so in Snap’s most valuable market, North America.

This was a one-two punch that Snap has yet to recover from: the self-inflicted wound of a poorly implemented redesign and the external, existential threat posed by Instagram that stole precious mindshare from Snap with a competing product. Snapchat may have been the innovator, but Instagram nailed the execution of its Stories product far more effectively than Snapchat had. One of the most common criticisms of Snapchat was its inaccessibility to new users. The app’s onboarding UX did a poor job of summarizing the core functionality of the app—so much so that Snapchat included a 10-slide deck as part of its SEC paperwork that showed older investors how to actually use the app. Instagram Stories, on the other hand, was almost effortlessly easy to use compared to Snapchat.

Snap’s disastrous redesign was responsible for many of the company’s problems during this period. However, the problematic redesign was symptomatic of larger problems—the same problems that former Snap employees had spoken of in The Daily Beast’s damning reporting. Several employees had described Spiegel as paranoid and a control freak, but what should have concerned investors wasn’t Spiegel’s temperament but his reluctance to act upon the data. There’s no hard evidence that Spiegel and Snap’s executive team flat-out ignored the company’s user data, but the catastrophic redesign was clearly the result of a company struggling to figure out how to move beyond the product’s core functionality.

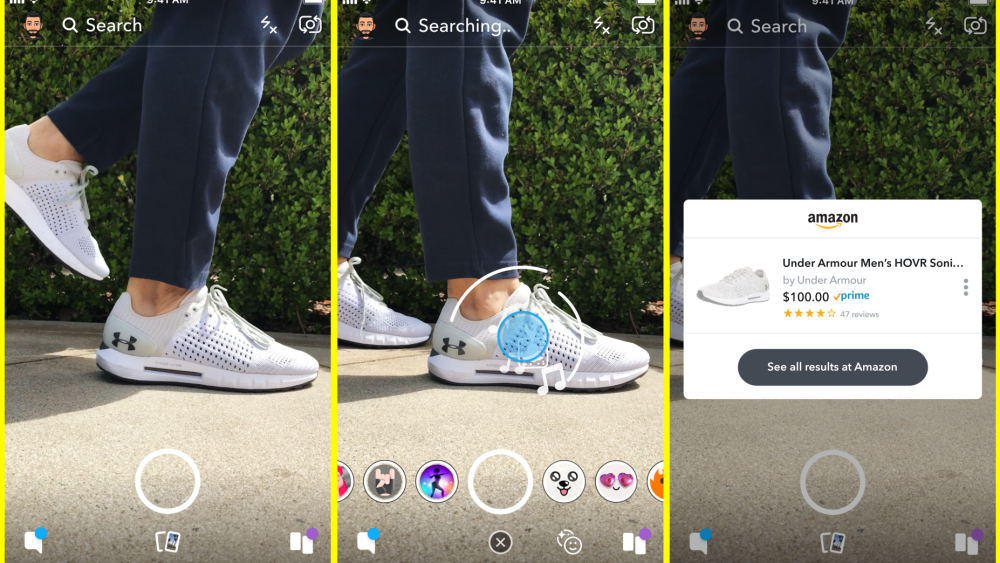

Despite Snap’s struggles, the company continued to try and find its place in a rapidly changing social media ecosystem. In September 2018, Snap introduced a visual search feature developed in partnership with Amazon.

The underlying technology behind Snap’s visual search was remarkable. The feature was highly accurate and hinted at the sophistication of the image-recognition algorithms that powered Snap’s visual search. However, while the technology and functionality were impressive, Snap’s decision to move laterally into ecommerce by means of visual search had many analysts scratching their heads. The real question wasn’t whether users would find the feature useful but whether users would bother to use it in the first place. The fact that this update also included barcode-scanning technology further muddied the waters.

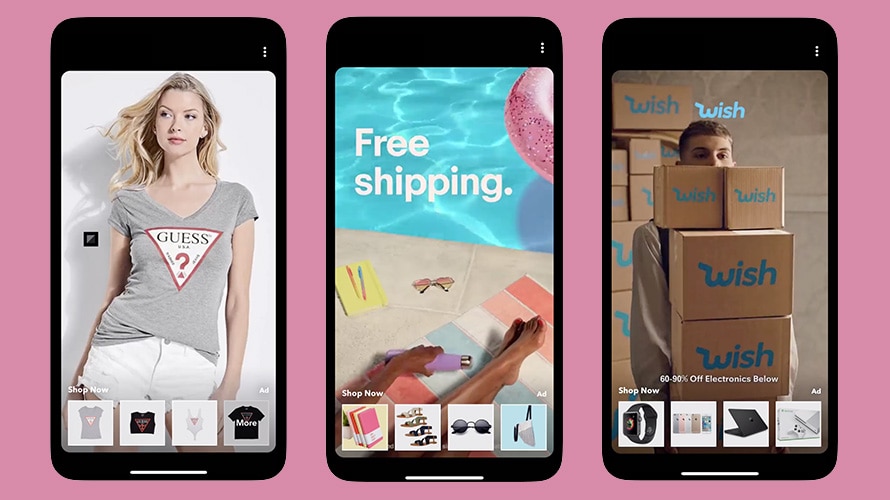

Snap raised more eyebrows in October 2018 when the platform doubled down on its apparent focus on ecommerce when it announced the launch of a brand-new advertising format, Collection Ads. Snap had been working on the pilot of Collection Ads with several brands since June, including eBay and apparel brand Guess. Snap told the industry press that these ads boasted engagement rates between 4x and 17x higher than individual Snap ads and said it was also refining its offline conversion tracking technology to provide greater insights for advertisers.

However, even this was a missed opportunity—Instagram had rolled out its own version of product catalog-style ads in June.

Snap’s moves to monetize its platform via integrations with Amazon and its renewed emphasis on expanding advertising options were welcomed by investors. However, many users’ confidence in Snap’s future has been badly shaken by the disastrous rollout of the unpopular redesign and the company’s informal culture of secrecy. Snap has made some progress with its monetization strategy, but what it needs to do urgently is restore both user and investor confidence and get back to its culture of experimentation and innovation in order to restore user engagement.

Where Could Snap Go from Here?

After the explosive growth and runaway hype of its earlier years, Snap’s more recent fortunes have been decidedly mixed. Despite its missteps, Snap is still well-positioned to rebound. Where could Snap go from here?

1. Greater focus on interactive content.

Snap has long been a champion of AR, but as more platforms incorporate AR into their products, Snap will have to innovate. This could mean a greater emphasis on interactive content like Snappables—Snap’s gamified mini-app that uses Lenses—particularly as AR becomes more heavily integrated into mainstream apps and software.

2. New 3D features.

Recently discovered patents seem to suggest that Snap is researching emerging technologies that will allow anybody to create 3D models just using their smartphone. This kind of technology could have an immense impact on its AR content and even as a standalone product, which makes it likely that we’ll see more 3D features coming to Snap in the near future.

3. Object-recognition video chat.

Similarly to its 3D modeling patent, Snap appears to be investing in new technologies that use object recognition tech to identify emotions based on scans of users’ faces. Interestingly, this patent seems to be aimed primarily at B2C advertisers and customer service professionals, suggesting a potentially bold—but risky—new direction for Snap.

What Can We Learn from Snap?

Despite its recent run of bad luck—or bad judgment—Snap still has plenty of invaluable lessons that any entrepreneur could benefit from.

1. Focus on an existing behavior—then make it easier.

Much of Snap’s early success and popularity can be attributed to how cleverly it leveraged a familiar, existing behavior—communicating privately by passing notes between friends in class—and repackaged it as a compelling digital experience for younger users, a traditionally overlooked market.Think about your product:

- Do your users intuitively understand how to use your product? Snapchat grew rapidly in its early days because its target market—primarily younger people, many of whom were still in school—grasped the concept of Snapchat and how to use it almost immediately. How can you leverage familiar, existing behaviors to make using your product more intuitive?

- Do certain demographics of your userbase find your product easier or more intuitive to use than others? In Snap’s case, many older users—including members of the tech press covering Snapchat in its early days—failed to really “get” what the product was about. This didn’t necessarily harm growth, but it certainly didn’t help much, either.

- The real brilliance of Snapchat, particularly in its first few years, was that it not only leveraged existing behaviors in the real world into a brand-new digital experience, but that it also mimicked how we converse in real life. What could you change about your product to emulate this? What parallels are there between how people behave offline and the experience of using your product online?

2. Expand on core features smartly.

Snap’s evolution as a product aligns closely with how we interact with each other and the world around us. Stories, in particular, was a brilliant move that expanded upon Snap’s core functionality to become even more natural and authentic.Take a look at your product’s core features:

- As a product, Snapchat was incredibly focused on nailing its core features early on. Over time, the company struggled to move beyond those features in a logical, meaningful way. How are you planning to move beyond your product’s central, defining features while remaining true to your original vision for your product?

- For much of its life, Snapchat has been more than willing to experiment and try new things. This culture of experimentation resulted in Stories, Snapchat’s most popular feature by far, but it also took the company further away from the identity of the product with tangential offerings such as Snapstreaks and Memories. How can you balance experimentation and expand smartly on your product’s core features?

- Taking this idea of expanding on core features smartly, can your product do so in a way that aligns with viable monetization strategies and investor expectations? Snap’s move into ecommerce, particularly with its visual recognition technology, was smart from a business perspective, but it didn’t feel like a natural extension of what the company was already doing. Is your product at similar risks when it comes to monetizing?

3. Go after product-market fit, but don’t neglect emerging competition.

Snap is an excellent example of a company that nailed product-market fit early on but ignored emerging competing products by rival companies—a grave mistake that Snap is still trying to figure out how to recover from.Think about where your product exists in the ecosystem of your industry:

- As a company, Snapchat seemed to falter after introducing some solid new features that drove initial growth. Does your mid- to long-term growth plan factor in the possibility of emerging competitors that could pose an existential threat to your product?

- Snapchat grew incredibly quickly early on by nailing product-market fit but ultimately failed to hedge against aggressive, formidable competitors such as Facebook. Even if your product is the only one of its kind in your vertical, how can you preemptively shore up potential weaknesses posed by potential copycats or rival products as you grow?

- Snapchat’s internal culture was a major driver of how quickly the product was able to reach product-market fit. However, that same culture was not necessarily equipped for the growth stage of Snapchat’s journey. What steps are you taking to transition from a focus on product-market fit to a mindset of growth as a company? What do you plan to do in order to make this transition?

Rose-Tinted Spectacles?

Snapchat has been one of the most fascinating success stories—and cautionary tales—in tech of the past decade. After an amazing period of strong product development and even stronger growth, Snapchat has also demonstrated the dangers of failing to listen to your users and what happens when you rely on assumptions rather than data.

However, Snapchat has plenty of potential. The real question now is whether the company can course-correct to overcome its recent troubles and reclaim its place as one of the most popular social apps in the world, or whether it will ultimately fade and disappear—just like its messages.