How Whole Foods Started an Organic Revolution and Became a $13 Billion Company

These days, it’s easier than ever to find locally grown organic produce. Every week, thousands of farmers’ markets spring up all over the country, offering healthy, delicious fruits and veggies grown by local farmers. Sales of organic produce hit $43B in 2016, growing by more than 8% over 2015’s sales. Compared with the 0.6% sales growth observed in the broader food retail sector during that same period, it’s clear that organic food matters to today’s consumers.

However, while organic food may be going through something of a renaissance, it wasn’t always easy to find locally sourced produce, especially for people living in cities. In the late 1970s, it was very difficult—so difficult, in fact, that one company saw an opportunity to capitalize on changing attitudes toward food and how we think about local agriculture.

That company was Whole Foods.

Since its humble beginnings as a health food store founded in Austin, Texas, in 1978, Whole Foods has become one of the biggest organic grocers in the United States and played a significant role in the growing popularity of organic produce and awareness of ethically sourced, locally produced food.

I got curious about the origins of Whole Foods, and how the company has evolved ever since. Here’s what I’ll cover in this article about what I learned:

- The importance of establishing a strong team with a clearly defined culture early on, and why this was crucial to Whole Foods’s survival in its earliest days;

- How Whole Foods first identified its target market—health- and socially conscious individuals who wanted to purchase locally grown, organic produce—and developed its unique value proposition to target this market;

- Why Whole Foods’s “conscious capitalism” resonated so strongly with consumers and helped the company become the premier organic grocer in the United States.

Whole Foods may be one of the largest organic grocers in North America today, but its origins are much more humble. The Whole Foods story began with a dream, a loan, and a catastrophic flood that pushed the company’s founders to their limit and almost destroyed the company before it even began.

1980–2002: Ambitious Acquisitions, Organic Growth

Although the Whole Foods story began in 1980, John Mackey and Renee Lawson Hardy opened SaferWay Natural Foods in Austin, Texas—the very first branch of what would later become Whole Foods—two years earlier, in 1978.

At that time, the landscape of commercial food retail was undergoing immense change. Propelled by two decades of rapid postwar economic growth, supermarkets had become a familiar sight across much of America. Shoppers had become accustomed to the growing range of frozen and prepackaged convenience foods that the supermarkets brought with them. Every day, new supermarkets opened in towns and cities all over the country, each one seemingly larger than the last.

But not all consumers were impressed by the ease and convenience promised by the expanding supermarket chains of the day. Canned goods were waning in popularity after enjoying more than 20 years of growth driven by fears of nuclear conflict during the Cold War. Many consumers longed for fresh, handpicked produce grown by local farmers—and it was this desire for authentic, locally grown produce that Mackey and Lawson Hardy capitalized on when they opened their SaferWay Natural Foods store, a tongue-in-cheek play on the Safeway supermarket brand.

Mackey and Lawson Hardy were just 25 and 21 years old, respectively, when they opened their store. The couple borrowed around $45,000 from friends and family to get their business off the ground. In 1980, SaferWay Natural Foods merged with another local food store, Clarksville Natural Grocery, and Whole Foods Market was born.

Mackey and Lawson Hardy didn’t set out to run just another grocery store. They wanted to change the way people thought about food and its role in the community. Rather than sourcing prepackaged fruits and vegetables laden with commercial pesticides from industrialized farms, the couple partnered with local farmers from the Austin area. The store rotated its stock frequently, and availability was determined by the time of year.

Today, this might seem like a shallow attempt to co-opt an idealized sense of authenticity that is largely lacking in commercial food production. For Mackey and Lawson Hardy, however, it was the core identity of their business—and it would become the unique value proposition that would drive much of Whole Foods’s growth over the next two decades.

Everything about Whole Foods Market was designed to cultivate and reinforce this sense of authenticity. The store’s signage was written on chalkboards. It wasn’t uncommon for farmers to show up at the store personally to deliver that week’s crop, the beds of their battered pickup trucks crammed with beets, carrots, heirloom tomatoes, and dozens of other veggies. Everything about the store was designed to be a genuine alternative to the mainstream supermarkets that Whole Foods Market’s laid-back customers avoided.

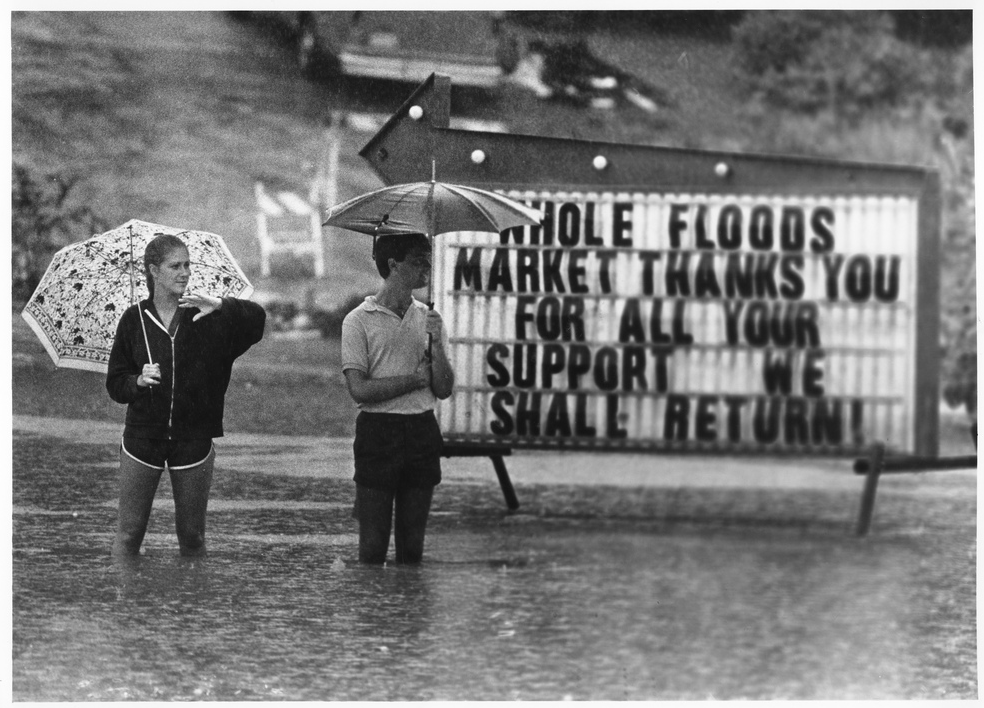

Of course, no business success story would be complete without a big, challenging event somewhere in the middle. Every growing business experiences challenges during the early days. But, not every company faces the kind of disaster that threatens to destroy the entire business before it’s even gotten off the ground. That is exactly what Whole Foods Market faced less than a year after opening its doors in 1980. On Memorial Day, 1981, the worst flood in a generation laid waste to much of the city of Austin. By the time the floodwaters receded, 13 people had lost their lives, and damages were estimated at approximately $35M (around $88M in 2018 dollars).

The damage caused by the flood was catastrophic. The store itself was submerged under eight feet of standing water. The entirety of the store’s inventory was ruined. It would take days to get the power back up. Total damages exceeded $400,000—and the store didn’t even have insurance.

It looked like Mackey and Lawson Hardy’s dream was over before it even began.

Fortunately, we know that this isn’t how their story turned out. In response to the flood, members of the community rallied to save the store. Neighbors helped to clean up the store, and the market’s creditors and vendors gave Mackey and Lawson Hardy some much-needed breathing room. Incredibly, Whole Foods Market reopened just 28 days after the flood.

“Our Team Members grew closer together, our commitment to our customers was greatly deepened, and we came to understand that we were actually making an important difference in people’s lives. If all of our stakeholders hadn’t cared so much about our company then and come together in support, Whole Foods Market would have ceased to exist.” — John Mackey, Co-founder, Whole Foods Market

Although the community response to the flood became a crucial part of the Whole Foods story, it was remarkable for another reason: It proved that Mackey and Lawson Hardy’s vision was working. Whole Foods Market wasn’t just another branch of another supermarket. It was a locally-owned market that had deep ties to the community, a bond strong enough to survive the worst flood to hit Austin in 70 years. In less than a year, Whole Foods Market had become a vital part of the fabric of the community—exactly what Mackey and Lawson Hardy set out to build.

Whole Foods Market came back from the flood stronger than ever. But while Mackey and Lawson Hardy had been able to rely on the generosity of family and friends to fund the opening of the original Whole Foods Market, they couldn’t count on doing so again. If they wanted to expand, they’d have to bootstrap their expansion plans—and that’s exactly what they did in 1984, when Whole Foods Market opened its second location in Houston, Texas. Just one year after the Houston store opened, Whole Foods Market had more than 600 employees. Soon after opening its doors in Houston, Whole Foods Market launched a third location in Dallas, Texas.

In 1988, Mackey and Lawson Hardy were eager to expand their vision beyond the Lone Star State. To achieve their ambitious growth plans, Mackey began approaching venture capitalists for investment funding. One VC after another turned him down. They just couldn’t see the vast potential market that Mackey and Lawson Hardy had identified as a meaningful alternative to the processed frozen foods favored by mainstream supermarkets of the time.

Here’s what one investor said:

“You know, John, I see you have got a pretty good business here, but it looks to me—I looked at all the stores—like you are a just a bunch of hippies, and you are just selling food to other hippies, and I don’t think that is a very big market.”

2002–2012: Spreading “Conscious Capitalism”

By 2002, Whole Foods had achieved fiscal sales of more than $2.7B. The company had just opened its first Canadian store in Toronto, the first Whole Foods outside the United States. The company was growing rapidly. The next stage in Whole Foods’s growth was the evolution of its original unique value proposition into the broader, more clearly defined corporate mission of “conscious capitalism.”

In the early 2000s, more sustainable approaches to consumerism were beginning to gain ground among mainstream consumers. Fair Trade coffee, locally grown organic produce, and even ethically produced honeys and other specialty products were becoming an increasingly common sight, even in larger, conventional supermarkets. But although consumers were gradually moving toward more ethical, sustainable ways of shopping, the movement itself lacked a name—something that Mackey was keen to capitalize on. That’s when the idea of “conscious capitalism” was born.

“One of the things that’s held back natural foods for a long time is that most of the other people in this business never really embraced capitalism the way I did.” — John Mackey

As Whole Foods continued to swallow entire natural grocery chains, the company began to think about how its original unique value proposition could be expanded beyond how it sourced produce. Whole Foods stores weren’t just getting bigger—they were also getting greener. In 2002, Whole Foods installed photovoltaic panels on the roof of its store in Berkeley, California, making Whole Foods the first national food retailer in the U.S. to use solar power. The following year, Whole Foods became the first certified organic grocer in the country and began supplying many of its stores in the mid-Atlantic region with wind power. In 2004, the Environmental Protection Agency awarded Whole Foods with its Green Power Leadership Award for the company’s commitment to sustainable energy, an accolade the chain retained for four consecutive years.

Whole Foods’s commitments to ethical business practices and environmental sustainability weren’t just logical extensions of the company’s original unique value proposition — they were a crucial element of the Whole Foods brand. Mackey knew that many consumers wanted the authenticity of locally grown produce and the convenience of modern supermarkets. He also knew that cultivating his company’s vision and brand values would further differentiate Whole Foods from an army of emerging competitors.

Whole Foods cared not only about good food—it also cared about saving the rain forests, protecting the oceans, and reducing carbon footprints. Whole Foods didn’t want to be just another chain of supermarkets. It wanted to be the supermarket for socially and environmentally responsible consumers. Shopping at Whole Foods wasn’t about choosing a grocery store. It was about choosing a lifestyle.

Mackey’s plans were certainly ambitious, and growth was brisk throughout the 2000s. However, while Whole Foods had been enthusiastically acquiring organic grocery stores that could help Whole Foods grow and access ready-made markets in affluent urban areas, many of the qualities of Whole Foods’s growing stores stood decidedly at odds with the company’s original mission. Whole Foods still sold organic produce grown by local farmers, but Whole Foods stores had become decidedly more indulgent: Some of the chain’s larger stores had introduced in-store restaurants, brick-oven pizzerias, gelato counters, and even luxury spas to attract the chain’s target demographic of young, affluent, socially conscious shoppers.

Whole Foods started as a grocery store for hippies. Now it was a grocery store for yuppies.

Despite the chain’s burgeoning identity crisis, Whole Foods continued to grow. Whole Foods hadn’t just grown as a grocery chain during the past decade—it had also grown as a brand. Whole Foods’s mission to sell ethically sourced organic groceries was resonating strongly with consumers, which in turn drove further growth and strengthened Whole Foods’s position as an influential retail brand in a rapidly growing vertical. What Whole Foods then needed to do was take its message to an entirely new generation of conscious consumers.

2012–Present: The Decline of Whole Foods, and the Amazon Acquisition

By 2012, Whole Foods was a household name across much of North America, and the retailer was enjoying the best year in the company’s 32-year history. There were 335 Whole Foods stores across the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Net sales stood at $11.7B, the equivalent of $932 in revenue for every square foot of store space. The company had enjoyed 11 consecutive quarters of growth. Whole Foods’s share price had reached an all-time high of $101 per share. To maintain this ambitious growth, Whole Foods needed to reach a new generation of conscientious consumers with its organic message.

However, while 2012 had been an incredible year for Whole Foods, it also marked the point at which the retailer’s fortunes began to change for the worse. Although Whole Foods had grown as a brand alongside its physical expansion across the U.S., the chain had begun to attract negative attention. Whole Foods had cultivated a reputation for the quality of its produce. Unfortunately, the chain was arguably as well-known for its high prices, leading to the store’s nickname: Whole Paycheck.

For all its organizational expertise and resources, Whole Foods had made a mistake that many startups make: It had been focusing almost exclusively on growth while neglecting the other elements of its business. To make matters worse, although Whole Foods had done more to advance the cause of organic produce than any other retailer, it had also inadvertently created an army of competitors who saw organic as the dramatic shift in consumer preferences it was. Virtually every supermarket chain and wholesaler was pushing organic produce aggressively, which drove down costs. Consumers not only had more choices than ever before—significantly weakening Whole Foods’s unique value proposition—but also now expected lower prices, thanks to intensifying competition.

While Whole Foods has done so much to inspire, create, and revolutionize the market for natural and organic, we now see it being the victim of its own success. The entrepreneurial culture that served it well in its growth mode now needs to be more process-oriented.” — Michael Lasser, Analyst, UBS

Although Whole Foods’s problems as a chain began to come to a head in 2012, heightened competition was not a recent development. In fact, according to many analysts, Whole Foods had been susceptible to the challenge of newer entrants in the organic produce vertical since at least 2006. Whole Foods believed it could outpace its emerging competition by opening more stores, but this shortsightedness and the chain’s hubris as the nation’s leading organic grocer were both instrumental in Whole Foods’s decline.

While the chain struggled to fend off the competition, Whole Foods continued to invest in the environmental and social causes that had helped it rise to dominance in the 2000s. In 2013, Whole Foods adopted a policy of complete transparency concerning the labeling of products containing genetically modified organisms. However, although Whole Foods had once been seen as a leader in the food retail sector, the chain was now playing catch-up.

In 2014, Whole Foods began accepting Apple Pay as a payment method, the first of several measures that Whole Foods took in an effort to attract younger shoppers. Later that year, Whole Foods partnered with Instacart to provide one-hour delivery to 15 metropolitan areas around the U.S. Although both developments were welcome conveniences to many Whole Foods shoppers, it was far too little, far too late. At one time, Whole Foods had been proactively innovative. Now, it was reactively protective of its dwindling market share.

In 2014, Whole Foods launched a nationwide advertising campaign of unprecedented scale for Whole Foods. The campaign was the first nationwide advertising campaign Whole Foods had ever launched, and it cost between $15M-20M. The spots featured Whole Foods’s private-label 365 Everyday Value brand heavily, as these products were and are much cheaper than the branded products sold at Whole Foods.

Although the campaign was ostensibly designed to combat the chain’s “Whole Paycheck” identity as a premium retailer, with prices to match, the campaign revealed that Whole Foods really didn’t understand the core problems facing it as a business—or if it did, the company chose to ignore them. Whole Foods knew its prices were among consumers’ biggest concerns, yet the advertising campaign attempted to reframe the problem as one of values; Whole Foods prices were justified because other retailers just couldn’t compete in terms of quality. Except this wasn’t true. Competing retailers like Costco and Walmart had made incredible gains in the organic produce market by selling quality organic fruit and vegetables at significantly lower prices.

Whole Foods’s once-unique value proposition had been co-opted by mainstream grocery stores and supermarkets, right down to the rustic chalkboard signage. Beyond the lavish but ultimately frivolous in-store amenities available at some locations, there was now virtually nothing to differentiate Whole Foods stores from any other supermarket in a meaningful way—and it didn’t take long for this to manifest in Whole Foods’s net sales.

Between 2005 and 2015, sales of organic food in the U.S. increased by 209% to a record-breaking $43B in 2015 alone. That same year, Whole Foods reported a decline in comparable store sales, a metric used in retail to calculate net sales by excluding the impact of new stores opening, for the first time since 2009. The company’s share value plummeted by 40%.

“Increased competition has forced us to look more closely at our pricing strategy and do a better job of conveying our value offerings—we look at it as a good thing because it forces us to do better. Nobody in the industry can match the level of quality standards we maintain across all departments, so it’s about balancing the quality with value to ensure there’s something for everyone in our stores.” — John Mackey

In many ways, Whole Foods became a victim of its own success. Mackey and Lawson Hardy may have been much more idealistic about the future of organic agriculture in America when they opened their SaferWay Market back in 1978, but the organic revolution they helped usher in had turned against them. Whole Foods had identified and targeted a small but growing market before anyone else. It successfully combined the convenience and ease of modern supermarkets with the rustic charm and authenticity of a mom-and-pop natural foods store. It focused on quality at a time when most supermarkets were prioritizing frozen convenience foods. But for all its innovation, one of the company’s biggest mistakes was failing to recognize just how glaring a vulnerability its pricing really was and what potential impact this would ultimately have on the Whole Foods brand.

By the time Whole Foods realized its reputation for high prices was the company’s Achilles heel, it was too late. The chain attempted to offset its negative reputation by pivoting away from its premium lines in favor of its 365 Everyday Value private-label brand. It began to open dedicated 365 by Whole Foods-branded stores, the first of which opened in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles in May 2016. However, while the focus of these stores was on the chain’s popular private-label brand, the 28,000-square-foot store still had many of the luxurious in-store amenities seen at many of its larger stores.

These features may have been popular with some shoppers, but their inclusion at the 365 by Whole Foods stores revealed that the chain still didn’t understand the most fundamental problems facing Whole Foods as a business. Some Whole Foods customers undoubtedly enjoyed the in-store spas and the broad selection of artisanal craft beers, but most shoppers wanted organic, locally grown produce that they could afford—particularly in cities like Los Angeles, in which the costs of living were rising rapidly.

Having tried and failed to shift the public’s focus away from Whole Foods’s pricing, the chain relented and began lowering prices across the board. But even this begrudging measure had little effect on Whole Foods’s troubles. In February 2017, after six consecutive quarters of declining sales, Whole Foods closed nine stores across the U.S., including a location in Chicago, as well as stores in Arizona, California, Colorado, Georgia, New Mexico, and Utah. It was the first time the company had actively downsized since 2008.

The chain continued to invest in ethically sourced products in 2017. The chain introduced a policy of sourcing canned tuna only from traceable, sustainable stocks. It implemented new, improved ethical standards in the production of eggs for Whole Foods’s 365 Everyday Value line. Whole Foods was awarded the Cage-Free Award from animal welfare organization Compassion in World Farming. However, while Whole Foods continued to demonstrate its commitment to ethically sourced food, the retailer was out of ideas. Sales continued to fall, and amid growing speculation of a forthcoming sale, it was announced that Amazon had acquired Whole Foods for $13.7B.

“We’re determined to make healthy and organic food affordable for everyone. Everybody should be able to eat Whole Foods Market quality — we will lower prices without compromising Whole Foods Market’s long-held commitment to the highest standards.” — Jeff Wilke, CEO, Amazon Worldwide Consumer

Almost immediately, Amazon brought its considerable purchasing power to bear on its new acquisition by slashing many of the chain’s prices. It’s no accident that pricing was the very first thing Amazon mentioned in the press release announcing the acquisition. Shortly after the news broke, some analysts began to question whether Amazon was a solid ideological fit for a socially and environmentally conscious retailer like Whole Foods. But this line of thinking misses the point of the acquisition entirely.

Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods wasn’t about ideology. It was about Amazon’s need for instant entry into an intensely competitive vertical. For Amazon, the timing couldn’t have been better. Whole Foods was sinking fast, with nowhere to turn, and facing increasing hostility from an already belligerent board of activist investors. With the acquisition of Whole Foods, Amazon is preemptively positioning itself to become as integral to the way we shop for groceries as it is to the way we shop for everything else. With the online grocery vertical poised to grow fivefold by 2025, to an incredible $100B, Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods makes plenty of sense. During the period from September through December 2017, sales at AmazonFresh increased by 35% to $135M, demonstrating just how strategically effective Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods has been in a short time.

However, while Whole Foods gave Amazon the near-overnight access into the growing food retail sector it had been looking for, that wasn’t the only reason Whole Foods was such a smart investment for Amazon. The chain’s predominantly urban and upper-class suburban locations are perfect for Amazon’s already extensive nationwide distribution network. Even if the stores themselves were completely empty, their locations would be almost as valuable as distribution hubs as they are as grocery stores. Rather than custom-building new distribution centers for its Fresh grocery delivery business, all Amazon has to do is retrofit its Whole Foods locations. Amazon has already begun offering Prime subscribers free, two-hour delivery service from Whole Foods stores in several cities across the U.S., a service Amazon will no doubt expand aggressively in the coming months.

While Whole Foods will undoubtedly continue to drive significant revenue for Amazon, its future as a brand is uncertain. Amazon will certainly benefit from Whole Foods’s predominantly affluent, middle-class customer base, its conscientious brand values, and its strong private-label line of products. However, to what extent Whole Foods remains a distinct corporate entity from its parent company—and whether the chain will retain its strong commitment to environmental and social causes—remains to be seen.

Where Whole Foods Could Go from Here

Amazon didn’t just gain practically overnight access to America’s highly competitive grocery retail market when it acquired Whole Foods last year—it gained a beloved brand with a strong, loyal consumer following defined by its commitment to conscious capitalism and ethical business practices. Where could Whole Foods go from here?

1. Greater emphasis on Whole Foods’ s Everyday 365 Value private-label brand.

As competition in grocery retail intensifies, Amazon will face continued pressure to keep prices static, or even lower them, in a bid to attract new customers. The strength and popularity of Whole Foods’s private-label Everyday 365 Value product line is one of the best ways for Amazon to ensure sales and revenue growth, meaning greater emphasis on these products seems practically inevitable—particularly in light of the growing popularity of private-label goods among millennial consumers and ongoing financial uncertainties driving adoption of private-label brands more broadly.

2. Further market consolidation driven by aggressive acquisitions.

Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods was a clever strategic move, but its position in grocery retail is far from uncontested. To fend off emerging and established competitors, Amazon could further consolidate its purchasing power in the space by aggressively acquiring other companies that could pose a threat to Amazon’s dominance or further bolster its online business, such as Instacart.

3. Deeper integration with/synergy across Amazon services.

Both Amazon’s Prime Now and Amazon Fresh have proved popular with consumers. One potential move Amazon could make is to further integrate the Whole Foods brand into these services, as well as tertiary products that have yet to make as significant an impact, such as Amazon’s Dash buttons, which could be integrated with Whole Foods’s Everyday 365 Value label.

3 Lessons We Can Learn from Whole Foods

Although the brand faltered in the years leading up to its acquisition, Whole Foods’s journey from a granola organic market to one of the largest, most profitable grocery retail brands in the world is as impressive as it is inspirational. Here are three lessons entrepreneurs should take away from Whole Foods’s incredible story:

1. Establishing a strong culture and trusted team early on is critical to survival.

The catastrophic flood of 1981 could have ended Whole Foods’s story before it really began, but the strength and resolve of the company’s early team allowed them to pull together and overcome an incredible setback.

Think about your team and key personnel, then answer the following questions:

- Besides emerging competitors or incumbent businesses, what are the biggest potential threats to the survival of your company? Does your product’s survival depend on maintaining the status quo? For Spotify, securing licensing agreements with major record labels was literally fundamental to the survival of the company. For TurboTax, proposed simplifications to the federal tax system posed an existential threat to Intuit’s flagship product. Are you facing any similarly crucial existential threats, and if so, how are you planning to mitigate them?

- Could your current team realistically respond to a crisis of the same magnitude as the historic Austin flood of 1981? If not, why not? Of your current team, who would you trust most in a crisis, and why? How can you attract more people like that? Can you cultivate the qualities this individual has across your company?

- What kind of culture are you building at your company? Would your team pull together as Whole Foods Market’s staff did in the wake of the flood, or would your business sink? What proactive measures are you taking at your company to cultivate the kind of culture you want to create?

2. Find a growing market, and target that market with a truly unique value proposition.

Mackey and Lawson Hardy identified an underserved yet growing market for their vision and then went after that market with a value proposition that was truly unique at the time. This is exactly what every entrepreneur should do with their own ventures—find an opportunity, identify the most urgent problems within that opportunity, and then solve that problem better than anyone else.

Take a look at your sector or vertical and think about the following:

- What attracted you to your vertical initially? Was it the potential size of the market or the challenge of solving a specific problem? Be honest—if your company went under tomorrow, would your industry really be worse off? If not, why not?

- Are you the only major player in a small market, or one of many smaller players in a larger market? When Whole Foods opened its first store, selling organic produce grown by local farmers was a genuine differentiator—the chain’s mistake was relying on this unique value proposition for too long and to the exclusion of everything else. Are you in danger of making the same mistake?

- Is your target market growing because of heightened consumer demand, or because you’re offering a genuinely innovative product or service? If your product is truly unique, how are you future-proofing your company or product from emerging competitors and blatant copycat products?

3. Grow your unique value proposition alongside your company.

What began as a unique value proposition for Whole Foods soon evolved into a much broader, more aspirational corporate mission based on ethical business practices and sustainability. This wasn’t just smart branding—it was actually a significant competitive advantage and a genuine differentiator in a crowded space. This evolution of Whole Foods’s value prop mirrored the company’s core values as it grew as a business, and this is precisely what founders should aim to do with their own companies.

Think about what really sets your business apart from the competition, then answer the following questions:

- How can you logically and organically expand your unique value proposition as your company expands? What about when—not if—competing companies try to muscle in on your market with a similar product? Whole Foods’s original unique value proposition was selling organic, locally grown produce by community farmers. Over time, this developed into Whole Foods’s broader mission to change the way people think about food and its adoption of strong environmental-conservation causes. How can your company do the same?

- Many startups confuse the “value” part of their unique value proposition with the “unique” part. Put another way, just because an aspect of your product or service is unique doesn’t necessarily make it valuable—to your company or the consumer. What is it about your product that genuinely drives value for the customer?

- Which parts of your unique value prop are the most vulnerable to competition or emulation? For many years, Whole Foods was the only major organic grocer in North America—but the company was so successful in its mission to change the way we think about healthy eating, it inadvertently sabotaged itself in the long run by creating a legion of competitors. How can you avoid doing the same?

Healthy Eating, Healthy Competition

Few businesses have attempted to tackle such an ambitious goal as Whole Foods. Although the chain ultimately fell from grace due to shortsighted management decisions and savage competition in an already fiercely competitive vertical, its meteoric growth proves that big, bold ideas can and do change the world.

Amazon’s acquisition of the Whole Foods brand is bittersweet. On the one hand, Amazon is one of the very few retailers that could legitimately help more people affordably access the kind of healthy, organic produce Whole Foods is renowned for. On the other, it’s hard to think of two companies more ideologically opposed than Amazon and Whole Foods.

Although the Whole Foods that John Mackey and Renee Lawson Hardy envisioned way back in the late ’70s may be nothing more than a memory, it’s incredibly exciting to imagine what Amazon will do with its new business.