How Square Became a $30 Billion Company by Reimagining Payments

Prior to 2009, one of the greatest challenges facing small business owners wasn’t how to compete with huge e-commerce retailers like Amazon. It wasn’t finding skilled staff, negotiating the price of commercial real estate, or paying punitive taxes.

It was processing credit card payments.

In 2009, Square was launched as a simple, elegant, and inexpensive solution to a problem facing millions of small businesses across the U.S. and around the world—how to easily and conveniently accept credit card payments at the point of sale without being hammered by prohibitively expensive merchant services fees.

Since then, it has become one of the leading point-of-sale systems available, and—most impressively—has transcended its original market and gone upstream to become a serious contender against mobile payment systems and traditional merchant services alike.

However, what’s really remarkable about Square isn’t the product’s design—though that in itself is certainly its own triumph—but rather how well Square solved such a significant barrier to growth facing small businesses of all types before leveraging that position to serve larger businesses in bigger markets.

Here are a few of the things we’ll be examining in this post:

- Why payment processing was such a barrier for small businesses, and how Square solved this problem

- How the diversity of Square’s earliest adopters was invaluable to the product’s development

- How Square managed to grow rapidly and move upstream beyond the small business market

Square succeeded by solving a huge problem among an even bigger potential market—but the idea for what became a company with a $30 billion market cap originally began with a glassblower from St. Louis who sought help from his friend, Jack Dorsey.

2009-2013: A Big Problem—and a Bigger Market

Jim McKelvey had been blowing glass since the mid-1980s, when he first learned the basics of the craft at Washington University in his native St. Louis, Missouri. McKelvey spent years traveling the world serving as an apprentice to master glassblowers around the world. McKelvey continued to hone his craft and began selling artisanal glass faucets via the company he founded in 2001, Third Degree Glass Factory. The quality and craftsmanship of McKelvey’s work soon earned him numerous accolades, and he was at the height of his career when he first encountered the problem that would lead to the genesis of Square.

In 2009, McKelvey received a phone call from a prospective buyer in Panama, who told him that she wanted to purchase one of the artisanal glass bathroom faucets for which he had become renowned. The faucet was worth somewhere in the region of $3,000. The woman seemed delighted by the faucet she had chosen, and the sale was proceeding smoothly.

Until the customer told McKelvey she wanted to pay with her American Express card.

“I said, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t take American Express. Don’t you have a Visa card?’ And she says, ‘No,’ and then she goes through this thing about ‘Maybe my husband has one’ and ‘He’ll be back in a week.’ And I’m sitting here going, ‘God!’ because I’m about to lose the sale.” — Jim McKelvey

Prior to that eventful conversation, McKelvey had accepted Visa and MasterCard payments through his company. Most of his customers, however, paid by cash or check. By 2009, McKelvey’s reputation for quality work allowed him to charge premium prices for his glass, but that didn’t mean he could afford to lose a $3,000 sale.

McKelvey never did close the sale with the woman from Panama.

Most small business owners would have chalked it up as a loss and moved on—but not McKelvey. An entrepreneur at heart, McKelvey talked his problem over with a friend. That friend was Twitter co-founder, Jack Dorsey. At the time, Dorsey had expressed an interest in exploring the nascent electric-car market. However, both men agreed that the financial barriers to entry in starting a car company were too high. Aside from his entrepreneurial curiosity about electric cars, Dorsey was also interested in developing a new mobile product.

This gave McKelvey an idea.

“So I said, ‘What we ought to do is build a payment system to prevent little businesses from getting screwed the way they’ve been getting screwed, because it’s really tough if you’re a small businessman to accept payment cards. You pay a ton of money…2 or 3 percent is the beginning of it, and then you’ve got all these fees, and you’ve got these PCI [security] compliance requirements.” — Jim McKelvey

At that time, accepting credit cards was a financial impossibility for many small businesses and merchants. Depending on the card, processing costs could total as much as 6% of the gross sale. In the case of McKelvey’s lost sale of the glass faucet to the prospect in Panama, those fees would have exceeded $180—just for the convenience of accepting a card payment for a single sale.

McKelvey and Dorsey decided to launch Square as a solution to this urgent problem. The company’s name was not only a reference to the shape of its flagship Reader product but also a clever play on the phrase “square up,” a common term for settling one’s debt. (Other names floated as potential contenders included Squirrel, Stash, and Wallet—a moniker Square later repurposed for its short-lived, consumer-focused app of the same name.)

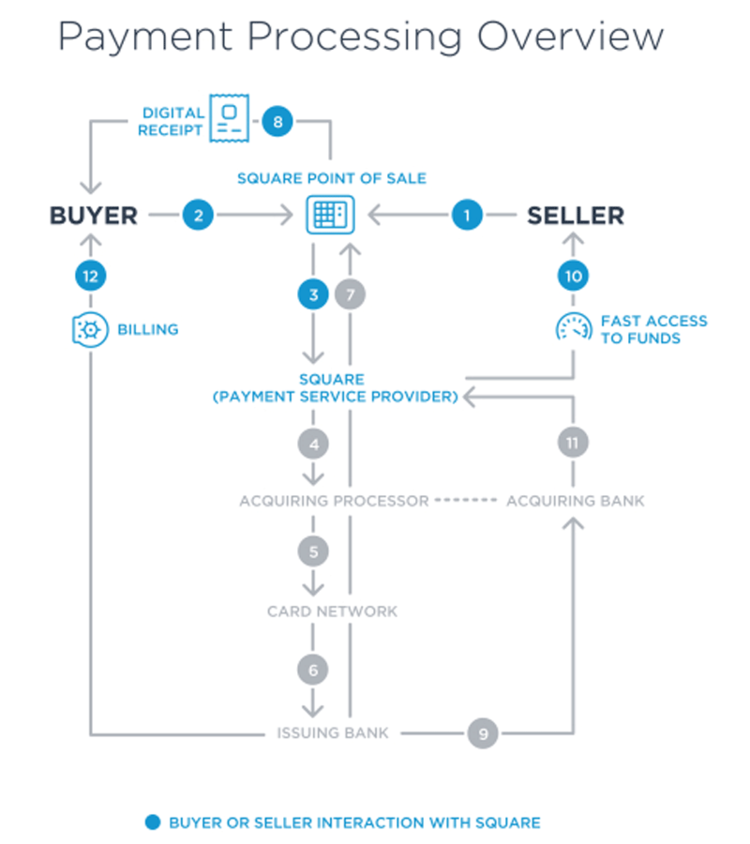

Their idea was simple. Square would be a simple way for small businesses to process credit card payments using a small dongle-style card reader that could be connected to a mobile device, effectively making the device a point-of-sale system. However, helping small businesses to accept card payments was only part of McKelvey and Dorsey’s solution. Dorsey in particular wanted to reimagine the entire concept of payments as a form of communication between merchant and customer. This meant designing an experience around payments, not just a product to facilitate the payments themselves. Square wanted to make processing card payments easy for small businesses and solopreneurs—but it also wanted to change how people thought about the entirety of the transaction experience.

Dorsey’s initial approach to creating buzz about his new company was as clever as it was unorthodox. He began by writing “140 Reasons Why Square Will Fail,” an itemized list of every conceivable obstacle that could jeopardize his nascent venture. Every entry in Dorsey’s list had a counterargument. Dorsey sent his exhaustive list of why his new company was doomed to failure to investors across Silicon Valley and beyond. Dorsey didn’t stop there, however. His list of reasons why Square would fail did exactly what Dorsey hoped it would—it secured him meetings with prominent investors who were intrigued by his idea. Dorsey began demonstrating a prototype of the Square Reader and the mobile app to potential investors, most of whom were highly impressed by the product. Toward the end of 2009, Square raised $10M as part of its Series A round, led by Khosla Ventures.

Amazingly, the first Square Readers were completely analog. The Readers themselves featured a tiny read head inside the plastic casing that functioned very similarly to a modified cassette-tape deck. This meant that the Reader devices were remarkably simple and inexpensive to manufacture. However, this simplicity came with a glaring disadvantage. Since the Readers were simple analog devices, some companies—including payment processing company Verifone—claimed that Square Readers were security risks. Verifone claimed that even a modestly skilled programmer could modify a Square Reader to function as a credit card skimmer, potentially exposing users’ card details. Dorsey refuted Verifone’s claims, saying the company’s assertions were “neither fair nor accurate.” Despite Dorsey’s view that Verifone’s claims were illegitimate, Square would introduce both SSL and PGP encryption by March 2012.

The simplicity of the Square Reader’s hardware and Dorsey’s exhaustive, preemptive approach to handling potential investor apprehensions weren’t the only major drivers of the early adoption of Square. There were two specific partnerships that helped propel Square into the mainstream. The first was a “strategic investment” from what should have been one of Square’s biggest competitors—credit card giant Visa.

“Square’s early success suggests that using Square and a mobile device, new types of merchants will now be able to accept payment and help grow their business via Visa’s global network with the security, speed and reliability we provide,” — John Partridge, former President, Visa

By the time Square accepted Visa’s investment, more than 100,000 new users were signing up for Square every month. What made this growth even more remarkable was the fact that this growth had been driven almost entirely by word of mouth. Square didn’t even have a dedicated sales team. In Q1 of 2011 alone, Square had already processed more than $66M in transactions and expected to process an additional $200M in Q2. Square didn’t “need” Visa’s support, but partnering with a potential enemy was a very smart strategic move. Visa’s support lent Square additional credibility at a crucial point in the company’s growth. In turn, Visa would get a cut of Square’s rapidly growing market share—and invaluable insight into how Square’s rapid growth could serve as a model for other financial tech companies in the future.

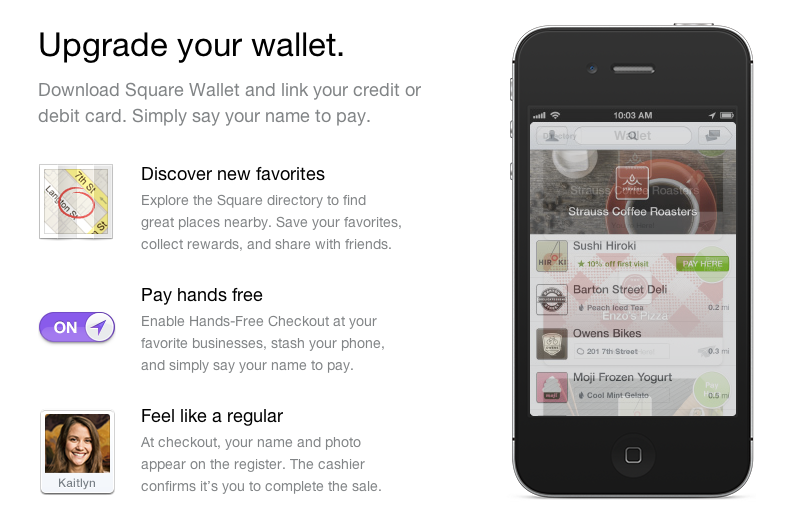

In 2011, Square took its first tentative steps into the world of consumer financial apps when it unveiled Square Wallet. What made Wallet such an ambitious product wasn’t its consumer focus—though that was a major step for the growing company—but the fact that Wallet was designed to effectively replace users’ physical debit and credit cards altogether. Users could connect their Wallet to a checking account and associated card, details of which were stored in Square’s systems, and use their Wallet to pay for everyday purchases simply by telling cashiers their name.

Wallet was also highly ambitious from a technical perspective. It was among the first financial tech app to leverage geofencing, the now common practice of establishing virtual boundaries using WiFi, cellular, and RFID data to offer users timely, location-based incentives such as coupons. This gave Wallet users instant access to a range of services, such as search functionality to find participating merchants nearby, user reviews of stores, menus, contact information, images, and directions.

Wallet wasn’t just a bold idea. It also aligned with Dorsey’s idealistic vision of payments driven by meaningful human interaction, rather than the cold, detached logic of credit card payments at that time. Wallet aimed to remove as many obstacles as possible between a consumer and a satisfying transaction, including the need to present cashiers with a physical card.

Dorsey saw a future in which payments were byproducts of everyday interactions, not the focus. Wallet also predated services that would later seek to improve upon the transactional experience including Apple Pay and Google’s Android Pay, which debuted in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Wallet ultimately failed, but it proved that Dorsey and his team had a larger vision of what Square could be as a company and its role in the rapidly changing landscape of consumer finance.

Square continued to solicit venture funding throughout 2011. In June, the company raised an additional $100M as part of its Series C round led by Kleiner Perkins. In December, Square accepted another $30M, bringing the company’s total venture funding to more than $150M in just two years.

“The plan includes growing the team, both in engineering and design, and increasing the awareness of Square, which means expanding the user base to the plumber, the piano teacher and the dog walker. As for product innovation, we will do a lot with the receipt. ‘Let’s make it interactive instead of something we throw away.’” — Jack Dorsey, co-founder, Square

The second pivotal partnership that drove massive growth for Square was an agreement that the company entered into with Apple in 2012. When Square partnered with Apple, the company had already been selling its Readers at more than 20,000 retail outlets including AT&T stores, Best Buy, Radio Shack, Staples, and Walgreen’s pharmacies. Cleverly, Square didn’t just sell its readers. Square understood that the true value of its Readers was in the experience. The company could have sold its Readers as a retail product and would have likely grown at a similar pace.

However, Square instead relied on the experience and convenience of its product as selling points, offering new users a $10 rebate on its Readers, which sold for $9.99. This effectively removed any potential objection to trying Square on the basis of cost and significantly reduced the already-low barrier to entry. In addition, the availability of Square Readers at Apple stores gave the emerging brand even greater credibility in the eyes of consumers. It also elevated and aligned Square’s already strong design aesthetic with Apple’s, which by that point had already made strong gains in its shift toward its status as a “lifestyle” brand of consumer electronics.

Key to Square’s early success was establishing key partnerships with well-known, nationwide companies that could offer immediate access to their credit card processing infrastructure, which was integrated into tens of thousands of physical stores. In August 2012, Square negotiated a partnership in which coffee retail giant Starbucks would use Square exclusively to process card payments in 7,000 of its locations. In addition to the exclusive partnership, Starbucks also agreed to invest $25M in Square, an agreement that gave Square a valuation of approximately $3.25B. As part of the deal, Starbucks’ CEO Howard Schultz was also given a seat on Square’s board.

Something else that was extraordinary about Square’s growth trajectory was how few major companies saw the small business market as a market in need of an urgent solution to a lasting problem. Before Square, any number of companies could have easily developed a similar product—but nobody did. Incredibly, not one major financial institution or commercial bank saw small business’ inability to cost-effectively accept credit card payments as the vast potential market it was. McKelvey and Dorsey could have focused on small businesses as their initial target market, such as coffee shops, florists, and bakeries.

Instead, they chose to focus on individual entrepreneurs like McKelvey. This wasn’t a deliberately exclusionary measure. McKelvey and Dorsey smartly identified solopreneurs who lacked any means of processing card payments as the potential Square users with the greatest need for a solution. Square’s users were artisans like McKelvey, but McKelvey and Dorsey wanted to help people launch businesses, not just help proprietors who had already established their businesses.

Processing card payments was only half of the equation Square hoped to solve. The ability to accept credit card payments was a huge problem for small businesses—but so was the fact that most small businesses had little to no actionable sales analytics data. This prompted Square to release its Register product in May 2011. Essentially an iPad that came preloaded with Square software, Register was designed as a replacement for entire cash register systems. The product was released as part of a limited nationwide launch across the U.S., which saw Square partner with approximately 50 merchants that would trial the new system. Register was immediately popular, and the timing of the launch couldn’t have been better. By the time Square debuted Register, the company had already shipped more than 500,000 Readers and processed more than $1B in gross payments.

“We want to take away the clutter and the paper, and get rid of the loyalty cards and get rid of the receipts. It’s really, really magical. It’s something that makes the experience awesome.” — Jack Dorsey, co-founder, Square

Dorsey’s talking points about the experience of using Square were more than just PR speak. It really was an effortless, frictionless experience. However, Square wasn’t content to just improve a flawed, existing system. Square wanted to redefine the entire idea of card payments, from start to finish—and that’s what Register set out to accomplish.

The urgent need for Square drove incredible growth during the product’s first two years. By May 2011, Square had shipped more than 500,000 Square Readers and processed more than $1B in payments—all without any dedicated sales teams. After a period of such explosive growth, Square was ready for the next phase of its plans for global domination—and it set about accomplishing these plans by refining its product and with a series of strategic acquisitions.

2013-2015: Reinventing the Cash Register

By 2013, Dorsey and his team realized that Square had significant commercial potential beyond its mobile Reader product. During this period, Square expanded up-market, targeting larger businesses with higher ACVs by building out its product to become a dedicated point-of-sale system and making strategic acquisitions.

Square kicked off 2013 by launching its first consumer-focused app, Cash. Essentially a means of sending and receiving money between users, Cash was initially limited to employees of Box, Pinterest, and Twitter during its closed beta period. Funds could be sent near-instantaneously, a very attractive alternative to the often days-long wait to transfer funds between two checking accounts. By making sending and receiving money between two people as fast and frictionless as possible, Square was further solidifying its brand as a “social” payments experience.

Functionally, Cash wasn’t dissimilar to PayPal and emerging competitor Stripe. The key differentiator was that Cash felt much faster and was actually fun to use. Cash felt more like a social app, not a banking or finance app. This was also a clever growth strategy, as Cash required users to connect a checking account to Square’s payment back-end infrastructure. This, in turn, would give Square even more user data with which it could further refine and develop its growing range of products.

Wallet may have been an ambitious approach to a common problem. However, Square had devoted considerably more time and attention to developing the experience of Wallet while neglecting its actual utility. User growth had been sluggish, and far fewer users signed up for Wallet than Square originally anticipated. The app performed poorly on Apple’s App Store, and in an interview with Re/Code, Square’s former Director of Product, Ajit Varma, claimed that the decision to terminate Wallet was made in just two internal meetings.

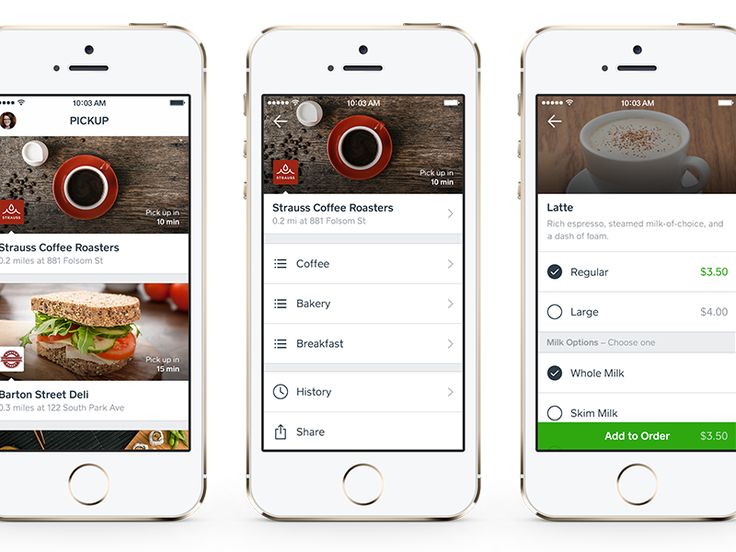

Wallet had been an interesting failure, but it wasn’t a total loss. Square applied what it had learned about consumer appetites for new financial products to its next major product, Order, which debuted shortly after the closure of Wallet in 2014. Order was Square’s attempt to capitalize on the rapidly growing food-ordering trend of the time. Grubhub and Seamless—both of which were owned by Aramark in 2014—had grown rapidly in key metropolitan areas across the U.S., including New York City and San Francisco. However, although Square took a smaller cut from orders made through its Order app (Grubhub charges started at 10% of the order total in 2014, up to a total potential cut of 14% for restaurants with high volumes of takeout orders), its cut of 8% was still significantly higher than the 2.75% charge applied to card payments processed through Square.

The company’s rationale for the higher rate was that online orders placed via Order would bring new customers to participating restaurants, justifying the 8% service charge. This may well have been true, but it was also incredibly risky. Square was undercutting food delivery apps, but its charges were approaching the very same threshold as the punitive merchant services fees Square had been launched to combat.

In August 2014, three months after launching Order, Square acquired food ordering service Caviar for $90M in stock. The acquisition of Caviar would be the first of many startups and established companies alike that Square would acquire in its mission to dominate the still-nascent food delivery service market.

One of the biggest headlines to come out of 2014 wasn’t Square’s acquisition of a food delivery company. It was the launch of Square Capital, an entirely new arm of the business. Square Capital began by offering merchant cash advances to certain businesses. However, what was most surprising about Square Capital wasn’t that Square started lending to small businesses and entrepreneurs—it was the terms of the advances themselves. Unlike loans from commercial banks, merchant cash advances through Square Capital had no set time frames by which the loans must be repaid. The advances were repaid by paying Square a percentage of all card sales over time. This made small-figure loans much more accessible to individuals who may have otherwise struggled to secure lines of business credit.

“With our recent investments, we’ll be able to increase the capital we’re advancing to businesses who need money to hire new employees, buy equipment, and add new locations.” — Faryl Ury, spokesperson, Square Capital

In November 2015, Square filed for an IPO. In the announcement, Square stated it would price its shares at between $11-13. This was problematic. Investors participating in Square’s last round of funding before its IPO were guaranteed a return on investment of at least 20%. Those investors, which included private equity firm Rizvi Traverse, bought approximately $150M of stock in 2014, giving Square a valuation of approximately $6B. Square’s initial share price of between $11-13 meant that Square would have to issue an additional 5.3M shares to compensate for the shortfall.

However, the reality was much worse than investors had feared. When Square formally went public, shares were priced at just $9, giving the company a valuation of $2.9B—less than half what analysts and investors had expected. Almost immediately, analysts began speculating about the company’s financial health. Some argued that Square’s disappointing IPO was a damning indictment of Silicon Valley’s so-called “unicorn” companies. Others claimed that Square’s valuation was an unreliable indication of the company’s prospects but voiced concerns about the company’s losses. Square had grown incredibly quickly, but the company was still hemorrhaging money, posting net losses of more than $53M on revenues of $332M in Q3 of 2015.

By 2015—just six years after first launching—Square was generating more than $850M in annual revenue and was worth almost $3B. The company’s problematic IPO had shaken investor and analyst confidence in the company, but Square had still carved out an impressive stake in an emerging market it had almost single-handedly created. Having dominated the nascent payments-processing industry, Square now set its sights on expanding even further and providing end-to-end financial services for businesses of all sizes—and proving its detractors wrong.

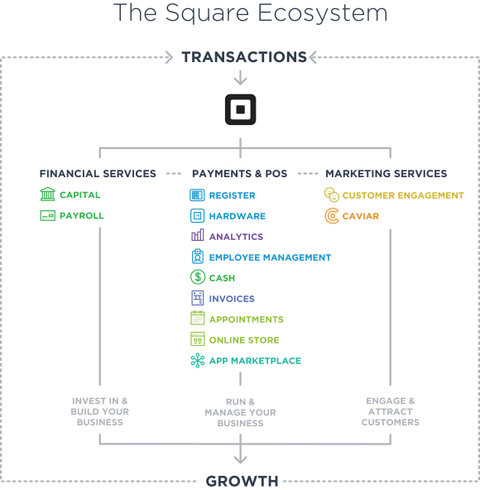

2016-Present: Expanding the Square Ecosystem

While Square appeared to be in trouble after going public, the company plowed ahead—solving problems, increasing revenue, and continuing to grow steadily. By 2016, millions of small businesses (and many larger companies) were using Square. Many analysts mistakenly wrote Square off after its IPO, believing that the company would no longer be as innovative in its approach now it had successfully gone public. However, Square didn’t rest on its laurels. It continued to experiment and refine its core products and became increasingly popular—and profitable. What Square needed now was a way to continue to expand even more aggressively into tangential services. It would do so by offering customers an increasingly broad range of financial services, including loan servicing.

Despite its rocky IPO, Square was riding high in early 2016. The company’s first quarterly earnings report as a public company exceeded analysts’ expectations, which in turn drove the price of Square’s stock up by more than 30% in one month. In terms of product, 2016 and 2017 were comparatively quiet for Square. The company didn’t make any major product updates during this period, but it did continue to acquire additional companies to strengthen and expand its core product offerings. In March 2016, Square acquired predictive analytics startup Framed Data as part of an undisclosed deal. Square had little interest in acquiring Framed Data’s technology. It was more interested in the expertise of its data scientists, whom Square soon put to work on its Capital team.

2016 also saw Square expand into the Australian market, the first such expansion the company had undertaken in almost three years. To attract new users in the competitive Australian market, Square offered Australian users an introductory rate of 1.9% for each transaction—significantly lower than the 2.75% it had charged users in the U.S. This pricing was both smart and necessary. The Australian market was far from uncontested, with PayPal and its subsidiary Braintree, Mint, and Tyro competing for market share.

In 2017, Square continued to strengthen its burgeoning food delivery and pickup business when it acquired dining pickup website OrderAhead for an undisclosed sum. At that time, OrderAhead was valued at approximately $30M. Square’s acquisition of OrderAhead strengthened its presence in the increasingly competitive food delivery space and complemented its earlier acquisition of Caviar by expanding its product-pickup service.

“With pickup, our goal is to expand Caviar from a delivery service to a more robust and fully fledged food ordering platform for restaurants and diners. We’ve been working on the pickup product feature within Caviar within the last few months. OrderAhead is more to accelerate our growth of pickup.” — Gokul Rajaram, Caviar Lead, Square

In November 2017, Square debuted its cashier-less Register product. Comprised of two iPads, one for the cashier and another for the customer, the Register was Square’s response to calls for a more professional, self-contained point-of-sale system. Register was aimed at businesses that wanted to cater to Square’s growing user base but needed a more robust point-of-sale system. Releasing its Register product at this point was a smart move by Square. The company had already grown rapidly thanks to the ease-of-use of Square’s Reader products. Now, it could target those small but growing businesses it could have targeted initially—the florists, bakers, and coffee shops that many analysts expected would be Square’s initial target market.

Two months later in January 2018, Square revealed that it had acquired yet another meal delivery business, Entrees On-Trays. Similarly to its acquisition of OrderAhead, the Entrees On-Trays deal was another play to solidify Square’s presence in the cutthroat food delivery market. In particular, Square wanted to dominate food delivery and pickup in the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area—a region with more restaurants per capita than anywhere else in America. Caviar had been operating in Dallas-Fort Worth since 2015, serving just 30 restaurants.

Early 2018 also saw Square revisit some of its earlier forays into consumer apps. In January, Square announced that its Cash app would now support the trading and exchange of bitcoin. This was smart, if only to demonstrate the company’s willingness to experiment with and embrace emerging financial technologies. Two months later, Cash introduced a feature that allowed users to accept paychecks by direct deposit. This was an aggressively smart play. Not only did this feature align with many millennials’ apprehension of mainstream banks, it also opened up Square to the enormous potential market of lower-income, underbanked communities not traditionally served by most commercial banks. The introduction of this functionality meant that Square could now offer many of the same services as mainstream banks, with the exception of cashing checks (which many younger banking customers are turning away from anyway) and wire transfers between two banking institutions—again, hardly an urgent need among the next generation of financial consumers.

“There’s a massive shift in consumer behavior and consumer trust. I think coming out of [the financial crisis], millennials have a massive distrust of existing financial services. They tend to trust technology more than the recognized stalwart brands, like a JPMorgan Chase or a Wells Fargo.” — Rick Yang, Partner, New Enterprise Associates

By late spring of 2018, Square had acquired at least nine different companies, each of which strengthened and complemented Square’s broader mission. However, Square’s most unorthodox acquisition to date came in April 2018 when it paid $365M for online website building service, Weebly.

At face value, the Weebly acquisition was smart. Recognizing the threat posed by competing services such as Squarespace, Square’s purchase of Weebly would allow the company to offer end-to-end website creation services for solopreneurs and the tiniest of new, small businesses before providing them with an increasingly broad range of financial services. Square didn’t want to just serve the small business market. Square wanted to help this market grow rapidly—along with its own userbase. It was also a great way for Square to make inroads in overseas markets. At the time of its acquisition, approximately 40% of Weebly’s userbase was outside the United States.

The following month, Square once again doubled down on its growing restaurant service business when it announced the launch of Square for Restaurants. Not only would Square for Restaurants eliminate the need for a separate system for Caviar orders—an unfortunate necessity that had forced many participating eateries to operate and maintain two separate payments systems—it would also integrate seamlessly with Square’s other service offerings, including Capital and Payroll. Square for Restaurants also solved an irritating problem for many restaurants by centralizing payments and orders for the many food delivery services that had become available, including Grubhub, Foodler, Uber Eats, and DoorDash. Rather than using a separate tablet for each service, Square for Restaurants could keep everything moving smoothly from a single integrated system.

The most recent product innovations by Square were the Square Reader SDK (Software Development Kit), which allows developers to create custom checkout experiences, and the introduction of lightning jack-compatible adapters for its Readers. The SDK, in particular, was a predictable but smart move for Square. Design has always been an integral part of the Square experience that Dorsey first envisioned back in 2009. By making it possible for businesses to customize their own checkout experiences, Square becomes that much more valuable to smaller companies seeking to improve the experience of shopping at their stores without taking on the technical overhead of creating such systems from scratch.

By August 2018, Square’s humble Reader product had come a very long way. They still closely resemble their analog ancestors but can now securely process chip-enabled cards in just two seconds. This was a problem Square had been eager to solve for some time. Although time spans of seconds might not seem of paramount importance, Square’s mission to process payments as quickly as possible is another example of how the experience of Square has informed and driven much of its product development.

Just as milliseconds can make a powerful difference in how responsive a website or app feels, every second a customer is forced to wait for their card to be processed was a second too long. This was one of the dozens of largely invisible improvements Square has made to its flagship product over the years. Square’s two-second processing time might not seem particularly exciting on its own, but the cumulative impact of such improvements has made Square a genuinely pleasurable product to use—quite an achievement for a solution to another “boring” problem.

With little real competition to speak of, Square is in a unique position to continue its remarkable growth trajectory. However, having dominated its market so thoroughly, Square’s real challenge will be to sustain its impressive growth while fending off emerging products from increasingly savvy e-commerce platforms like Shopify and rivals such as Clover.

Where Could Square Go from Here?

While Square does face emerging threats, its biggest challenge will be continuing to solve genuine problems for its increasingly large and diverse user base. Where could Square go from here?

1. Additional ancillary financial services.

It makes little sense for Square to become an alternative to mainstream commercial banks. A greater range of mainstream banking products would expose Square to significant risk and additional compliance requirements, all for a place at an already-crowded table. However, it seems likely that Square will continue to adopt a data-driven approach to the development of additional personal and small business finance products beyond loans. This may include a renewed focus on cryptocurrencies, given the gradual but steady gains these currencies have made into the mainstream.

2. More dedicated products for specific industries.

Square for Restaurants was a very smart play, given the unique financial challenges faced by these businesses and the intense competition in the food delivery space. Given the popularity and growth of Square for Restaurants, it seems highly probable that Square will continue to develop specialized products for specific industries and verticals. This could include further moves into more corporate payment processing products, as Square did when it began offering payroll services.

3. Betting big on blockchain.

Given Square’s considerable market share and resources, one potential move the company could make is to invest in and develop products around identity-based payment systems such as those made possible by blockchain technologies. Square already demonstrated a willingness to embrace emerging financial technologies by supporting bitcoin in its Cash app, and with institutional interest in cryptocurrencies on the rise, the possibility of Square at least researching such opportunities is high.

What Lessons Can We Learn from Square?

Square has become a major player in an intensely competitive space in just a few short years, a journey that has plenty of lessons to teach us:

1. Targeting an underserved market can help pull your company upstream.

Square smartly targeted a huge pain point among an even larger potential market, but it was the elegance of the product itself—its ease-of-use, simplicity, and low-friction experience—that helped the market transcend its original market and make the difficult move upstream.Take a moment to think about your product and its place in your industry:

- What would you need to do in order to make a successful move upmarket? Put another way, is there an improvement or change you could make to your existing product roadmap that could help you attract larger or more affluent customers later on?

- Square didn’t just disrupt the small business economy; it disrupted how we think about payments as a concept. Are you missing an opportunity to solve an even larger problem than the problem you’re tackling right now?

- Does your product create a new experience in solving a familiar problem? Square made accepting card payments not just financially feasible, but genuinely pleasurable. How could you emulate this in your own product?

2. Leveraging existing tailwinds can be amazingly effective.

Square was innovative and urgently needed as a product, but the company was clever to capitalize on existing tailwinds when it launched, most notably, the trend away from cash toward card-based payments. Square leveraged this tailwind to great effect and, in doing so, also helped propel and accelerate existing trends.Think hard about the problem you’re trying to solve with your product:

- Where will your industry be in two years? How about five years? Now think about where your product and company fit into this growth trajectory. What could you do to not only solve your users’ most urgent problems but take advantage of broader trends in your sector? Similarly, could any emerging technologies or changes in consumer behavior jeopardize your product’s success in the mid- to long-term?

- Does your product set trends or follow them? If it’s the former, how can you leverage your product’s status as a trendsetter to capitalize on broader trends in your industry? If it’s the latter, could you take advantage of wider changes in your sector to add more value to your users?

- Square solved a lasting and urgent problem for small businesses. However, perhaps more importantly, it did so in a way that felt great as an end-to-end experience. Does your product just solve a problem, or are you offering your users a new way of experiencing the solution to that problem?

3. Never stop experimenting.

Square has never been afraid to bet on the long-term. However, what really sets Square apart is its willingness to continually experiment until it found a working solution. Square’s culture of experimentation helped the company get closer and closer to the consumer, which has proven incredibly valuable and lucrative.Consider your company’s culture and answer the following questions:

- If you could do so entirely risk-free, what would be the single biggest experiment you’d run on your product? Once you have that idea in your mind, how can you break down this single, potentially risky experiment into smaller, more manageable A/B or multivariate tests?

- Think about the last experiment you decided against running. Why didn’t you run the experiment? Were you worried about what your users might think or what potential investors might think?

- Are you really listening to your users? Cultivating a culture of experimentation requires a degree of courage, but it also takes a lot of listening. Are you ignoring or overlooking potentially invaluable user feedback that you might not have considered otherwise?

It’s Hip to Be Square

Square not only solved a lasting problem for millions of small businesses worldwide but did so in a way that forced the mainstream financial sector to reevaluate what consumers want from financial products in today’s business environment. The company was smart to emphasize the importance of design and how this affected the overall experience but was careful to avoid developing a reputation for style over substance.

Your company may not have a celebrity founder like Jack Dorsey or the funds necessary to acquire your way upstream. That said, Square has adapted to and maneuvered within an incredibly competitive vertical that few companies have been able to disrupt in as powerful or lasting a way as Square has. I can’t wait to see what the company does next.