How Adobe Became a Successful $95 Billion SaaS Company

When we think about SaaS success stories, here are a few of the companies that come to mind: Salesforce, Shopify, Workday, Zendesk, LinkedIn. One that people don’t often think about? Adobe.

But Adobe has made a series of savvy business decisions to stay competitive and successful. The software company is best known for products like PostScript and Photoshop that paved the way for modern visual design, while acquisitions of companies like Omniture and Macromedia cemented their hold on the market.

One of their most impressive moves was their transition from a licensed software company to a completely cloud-based company. This was an incredibly expensive and arduous process, and is almost impossible for a company to get right—but Adobe did it, carving out a permanent place in the changing industry. And that’s only the latest example of how Adobe has continually made difficult and forward-thinking decisions to help the company thrive.

Just like Microsoft or SAP, Adobe has made a lot of tough product decisions over the past 35 years, shifted and reconfigured the business, and maintained a loyal core audience. These decisions have paid off—Adobe closed 2017 with over $7 billion in annual revenue, and they currently have a market cap of over $95 billion.

To achieve this level of success, Adobe had to make smart product, market, and financial decisions. We’ll take a look at how they:

- Helped create the desktop publishing revolution with some of their first successful software products for designers

- Made a series of smart acquisitions to broaden their market and move more into the consumer space

- Fully transitioned from a licensed software company to a cloud SaaS company

Let’s dive into Adobe’s company journey.

1982 – 1993: The Desktop Publishing Revolution

Many people have heard of Adobe because of their best-in-class photo-editing app, Photoshop. It’s so popular that it has become a verb—just like Google and Xerox.

“Don’t like how that photo looks? Just Photoshop it.”

But Adobe isn’t just a company that sells design tools anymore. Over the last 35 years they’ve grown from a company with a few visual design applications to a huge, diverse enterprise software provider.

Adobe founders John Warnock and Chuck Geschke met while working as engineers at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center. There, they worked on personal computers and laser printing, and realized that businesses and professionals needed more accessible publishing and printing software. They were able to turn this spark of an idea into a successful software company in these early years by doing two things really well:

- Strategic partnerships

- Smart product/market fit decisions

For the Adobe founders, the most important thing in the early stages of their company was bringing their initial idea to the market. Warnock and Geschke knew that businesses needed desktop printing software, but they realized it was going to take Xerox a long time to get to that market. So the two forty-year-old men in the middle of their careers decided to make a huge, risky move and go out on their own.

Their first product, the printing language PostScript, was their way of experimenting with desktop printing software. PostScript was a program that allowed users to print from personal computers to external printers. Adobe was literally at the forefront of mass digital image production.

They got hugely positive feedback on PostScript, especially from other major players in tech at the time, like Steve Jobs. When Jobs heard about PostScript, he approached Warnock and Geschke with an offer to partner their software with Apple’s hardware.

“We [at Apple] could quickly see that our hardware was going to be better than theirs [Adobe’s] and that their software was more advanced than what we were working on.” – Steve Jobs

This partnership was an important early step for Adobe. It generated a lot of attention and success, prompting an offer from yet another company, Aldus, for a three-sided partnership. Aldus made a product called PageMaker, a word and graphics manipulator. It was an ideal third piece to the puzzle because it could show a user just how sharp and responsive the Macintosh’s interface was, as well as how capable the PostScript printing program was.

The early success of this trio of products helped the Adobe founders realize that there was a bigger, more important market for professional desktop applications that allowed users to manipulate things visually, rather than just with code. Adobe’s next products followed this realization—they made editing images on a computer as easy as on a piece of paper.

Between products like PostScript, Photoshop, and Acrobat (all of which were at the bleeding edge of digital image production), and the novel file formats they used (like .PSD and .PDF), Adobe was able to set the industry standard. Part of Adobe’s early success wasn’t just in owning the applications for design, but in setting the standard for how people could utilize digital design going forward.

Let’s dive deeper into what this looked like in Adobe’s early years:

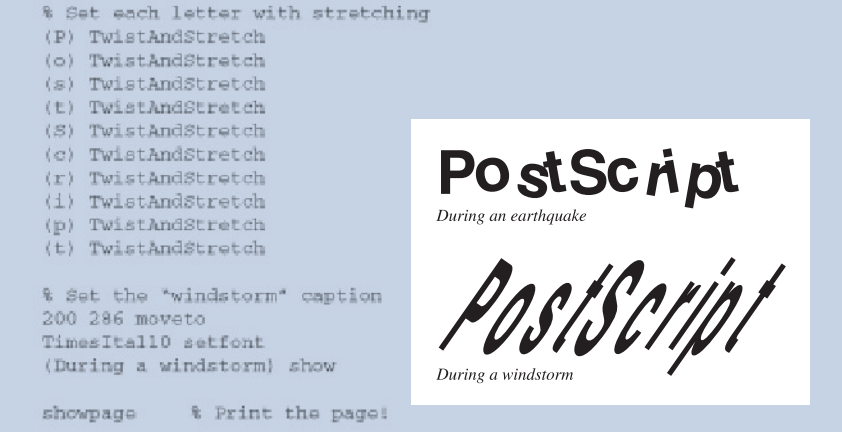

1983: Adobe released PostScript. The software could control output devices like laser printers from personal computers. Before PostScript, typesetting was only possible if you bought a system along with a special device, which was incompatible with any other devices. Personal computers could be connected to dot-matrix printers that printed low-quality characters. PostScript made good-quality printing possible from any device. Within just a year of PostScript’s release, the product brought in $83,000 for Adobe.

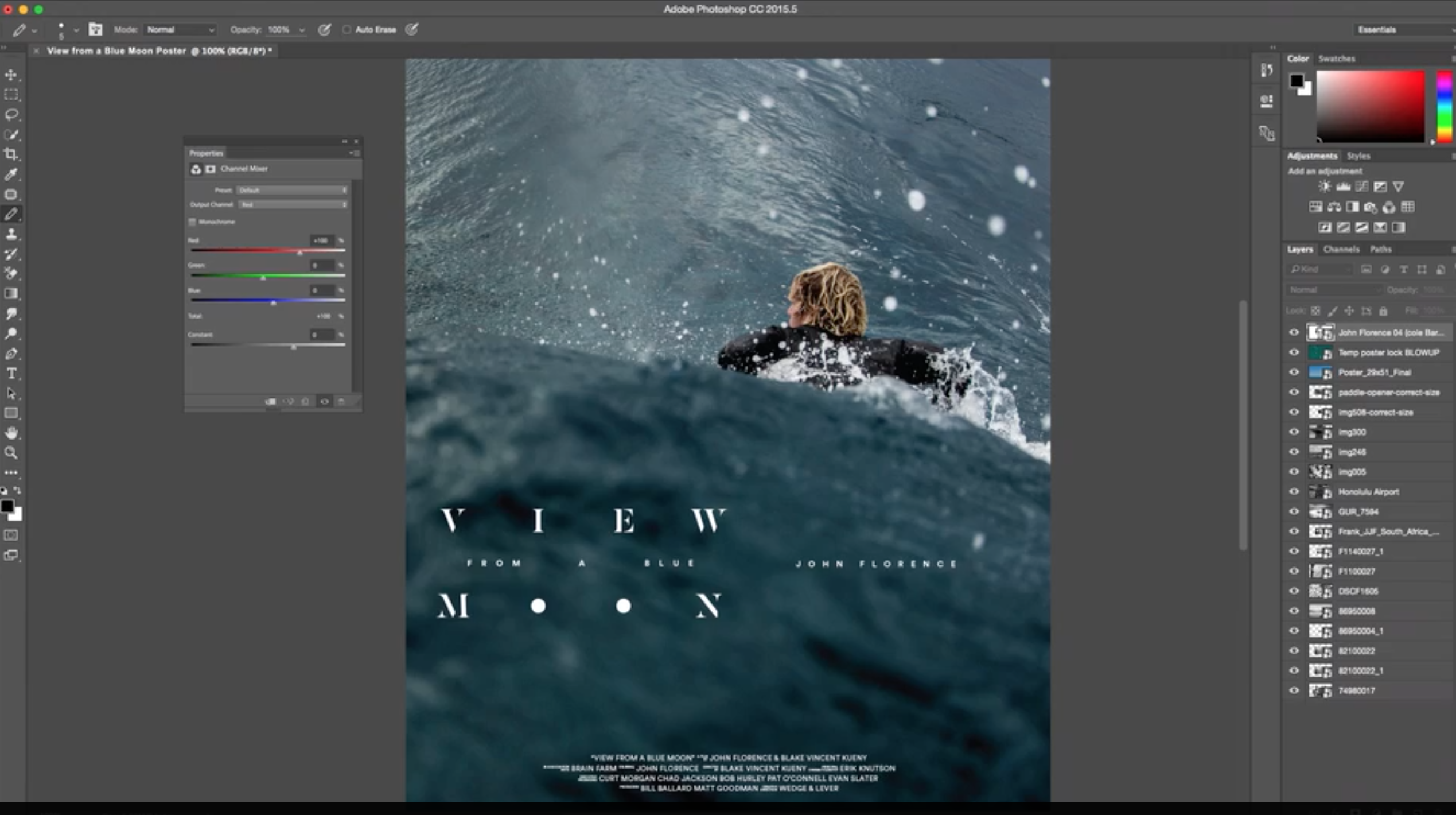

An early example of PostScript programming that shows how flexible the language was. [Source]

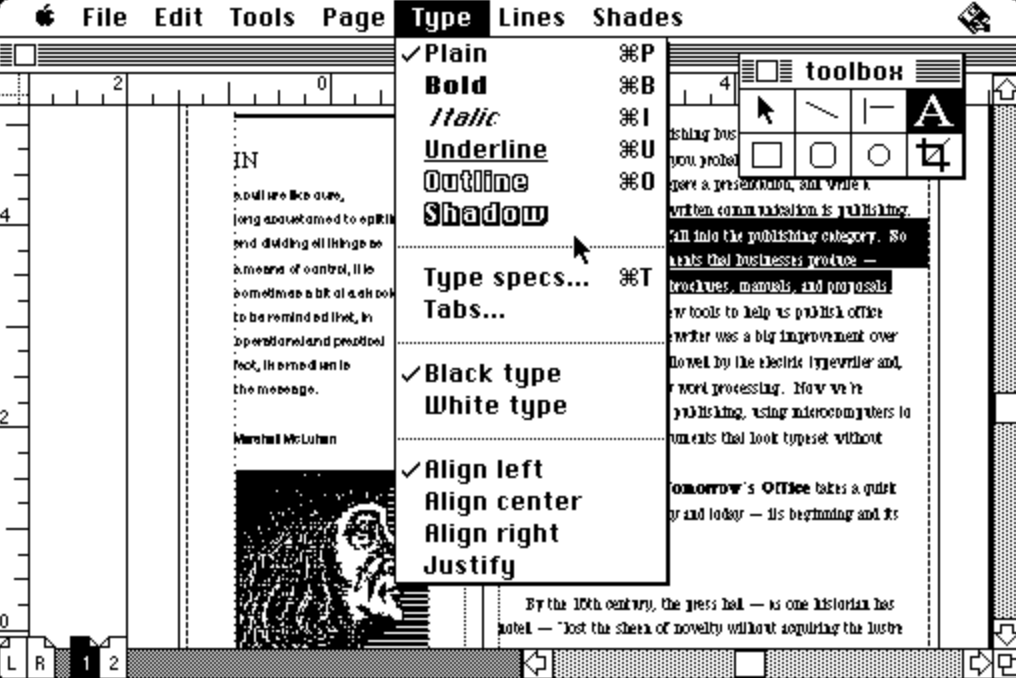

The PageMaker program on a Macintosh interface. Users could print what they created through PostScript. [Source]

The PageMaker program on a Macintosh interface. Users could print what they created through PostScript. [Source]

1987: Warnock was inspired to work on developing a drawing tool because he saw how his wife, a graphic designer, worked—and had a sense of what kind of software would be useful to her. In 1987, Adobe released Illustrator, which was especially remarkable for its Pen feature that allowed users to draw curved lines. The company sold it for $495, which was thousands of dollars cheaper than the graphic drawing software that was already available.

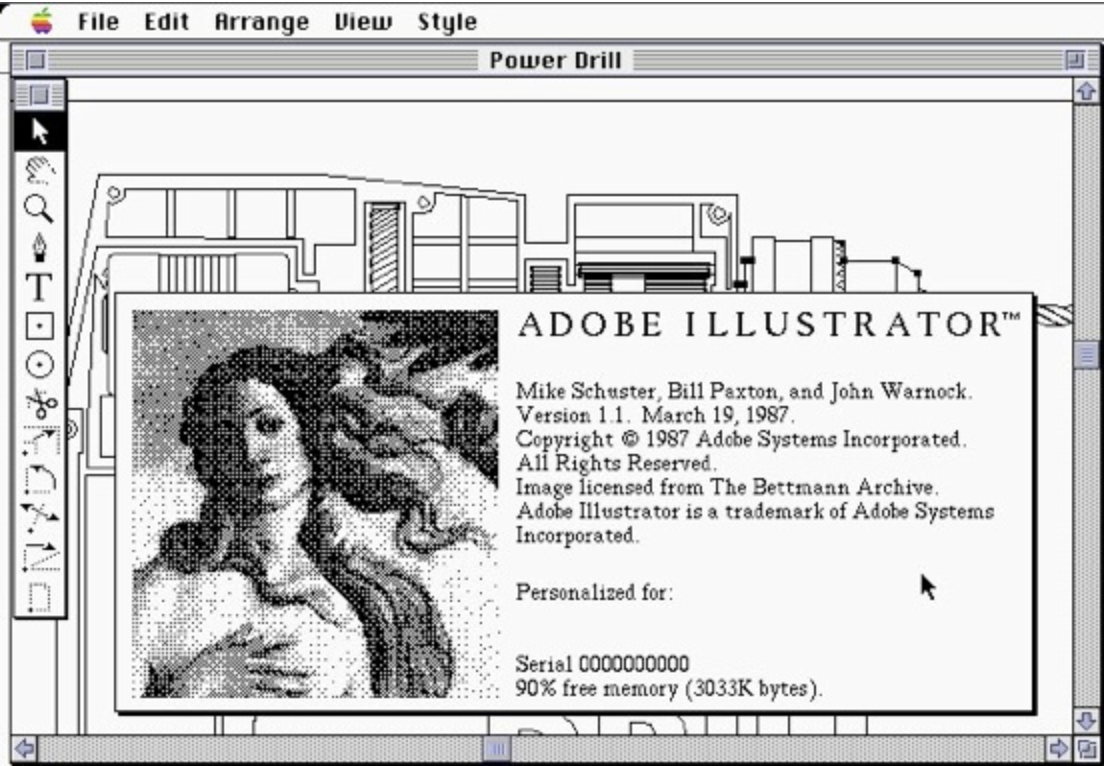

Adobe Illustrator in 1987. [Source]

Adobe Illustrator in 1987. [Source]

1988: Adobe was breaking even on Illustrator at about $19 million in revenue, seeing decent—but not skyrocketing—sales. To bolster the product, Adobe released Photoshop, a photo editing tool, as an add-on to Illustrator. Photoshop was an entirely new direction for Adobe because it allowed users to work on photos from external sources like a scanner, rather than building images from scratch. Adobe went in this direction because it broadened the potential use cases of Illustrator even more. But the Photoshop add-on wasn’t expected to have a huge revenue impact. At this point, revenue from PostScript—$82 million—was subsidizing the cost of these new applications.

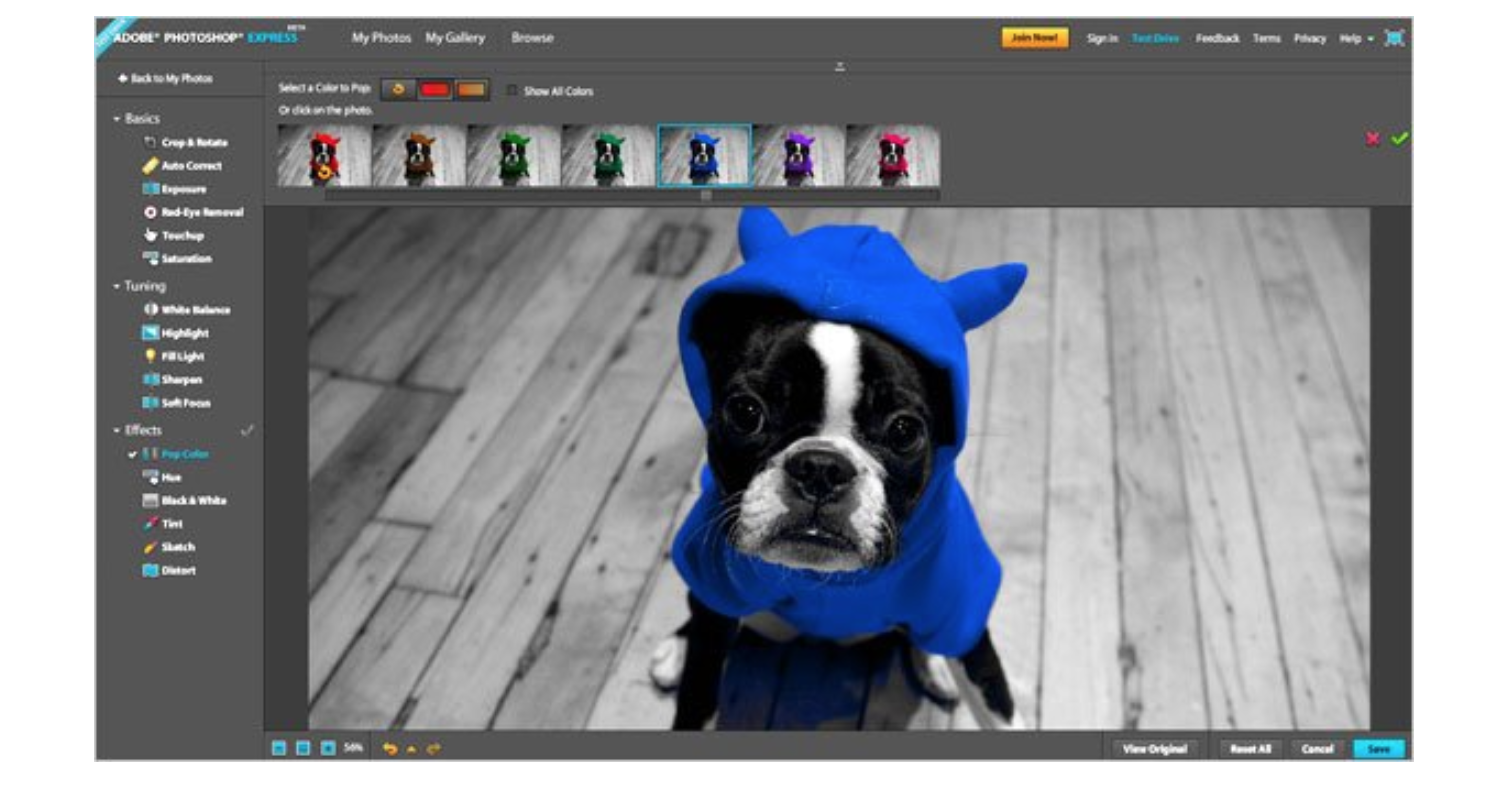

The earliest version of PhotoShop had basic photo editing functionality. [Source]

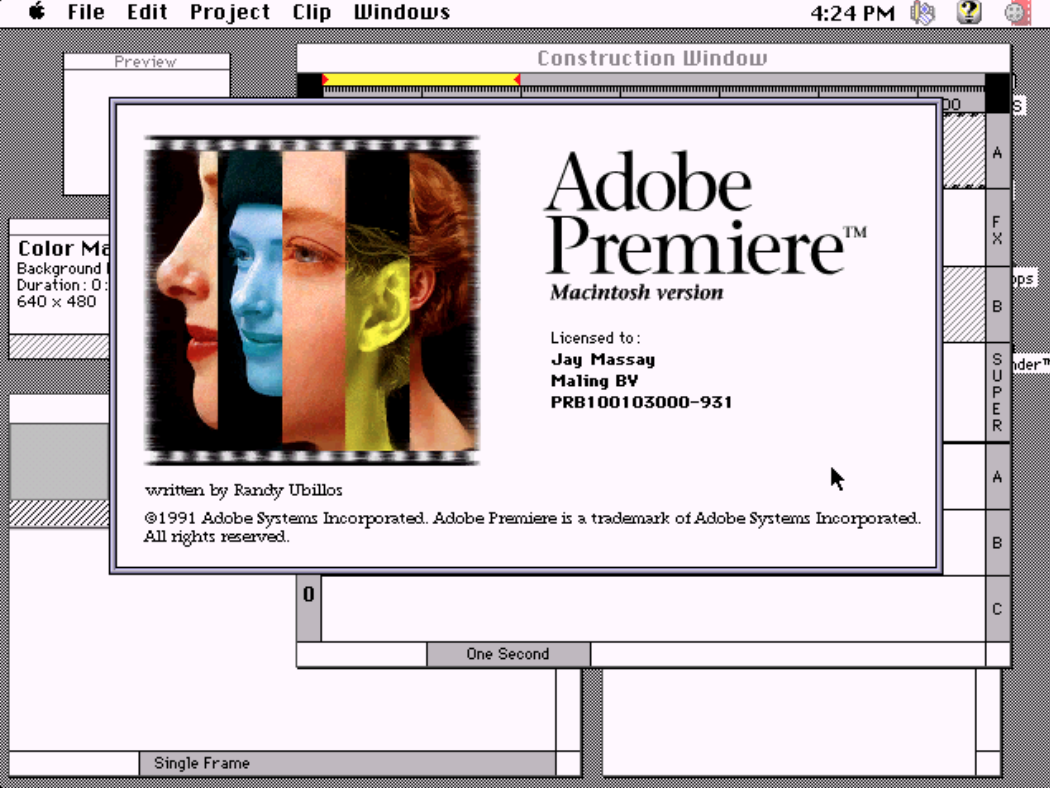

Adobe Premiere in 1991. [Source]

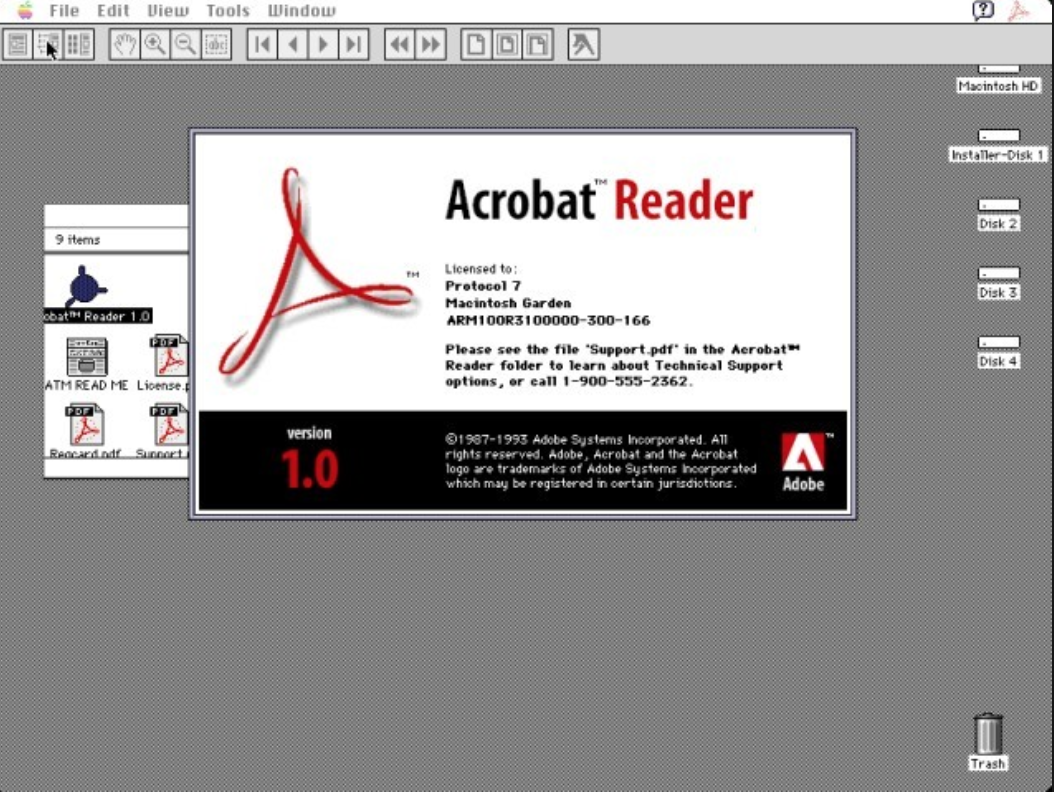

The interface of Acrobat reader in 1993. [Source]

Thanks to the growth of Photoshop, by 1993, profits for applications overtook profits for PostScript. Just four years earlier in 1989, 65% of the $121 million revenue was coming from PostScript alone. Now Warnock’s vision for an application business was coming to fruition. As popularity for the application products grew, Adobe engineers and designers worked closely together to keep updating Photoshop and adding new features, which compounded the product’s success.

Adobe’s decisions to appeal to a broad base of design-minded users with different applications was key. It wasn’t a totally intuitive decision because at first, PostScript was hugely successful and the apps seemed like unsuccessful side projects. But Adobe had a long-term vision. Bruce Nakao, former CFO, said, “The applications business lost money, but we kept plugging away at it because we knew PostScript could run out of gas.”

The runaway success of these apps for the core creative market helped Adobe reach $313 million in revenue by 1993. This revenue gave them capital to make important acquisitions, which would help them grow in the next stage of their business.

1994-2006: Acquisition Spree and the Digital Publishing Revolution

In Adobe’s first few years, they completely transformed desktop publishing by making it cheaper and simpler for businesses to print from their own computers. But as Adobe grew, the team needed to tackle many more challenges. Some of these came from the nature of the market changing around them:

- There was a shift from paper-based distribution to digital distribution

- There was more competition from other software companies making similar design tools

Adobe adapted to both of these changes by making a series of smart acquisitions that augmented their core strengths and slowly began to expand their market.

One of these important acquisitions was Aldus, the creator of PageMaker. Even though Adobe and Aldus had initially helped each other gain early success, they became increasingly similar companies going after the same market. In the years leading up to the acquisition, Aldus had been developing and acquiring tools that competed directly with Adobe’s—they released a drawing program called FreeHand, and a photo editing app called PhotoStyler.

Aldus FreeHand for Windows. [Source]

During this time, the internet was growing quickly, which gave people the opportunity to create and share images in increasing orders of magnitude. Adobe didn’t sit still. They acquired a competitor called Macromedia and absorbed products like Dreamweaver (a Photoshop competitor) and Flash, which the web was built on top of. This positioned the company to be an important part of the web’s new era.

These acquisitions added more products that Adobe could provide to users to help them create products for digital publishing. It also eliminated the threat of Aldus and Macromedia as competition by absorbing their talent and plans for expansion.

These acquisitions also opened a door to new consumer markets. Before them, Adobe was focused on business-grade tools for professionals. That changed after acquiring Aldus; the pre-acquisition team was working on a few small revenue-generating tools for consumers who wanted to dabble in design. The head of Aldus’s Consumer Division, Bruce Chizen, became the head of a new Consumer Products Division at Adobe.

By branching out beyond the creative professional market and into the consumer market, Adobe built a moat against competition and took steps toward making digital publishing more accessible to everyone.

Here’s how this played out:

1994: Adobe announced a “merger” with Aldus, which was really an acquisition. Even though the companies went after similar markets, Adobe’s profits were ten times those of Aldus’s—$49.3 million compared to $5.1 million. The company doubled in size from 1,000 to 2,000 employees and became the fifth-largest software company in the world.

1995: Although Photoshop was very successful as a web application, Adobe thought the internet was a phase; they weren’t focused on building out their products as web apps. This was a huge inflection point and a bad prediction for the company. That Adobe survived and thrived even when it missed the mark in such a huge way is a testament to how well they achieved product-market fit—and how well they continued to innovate on pre-existing and new products over the decades.

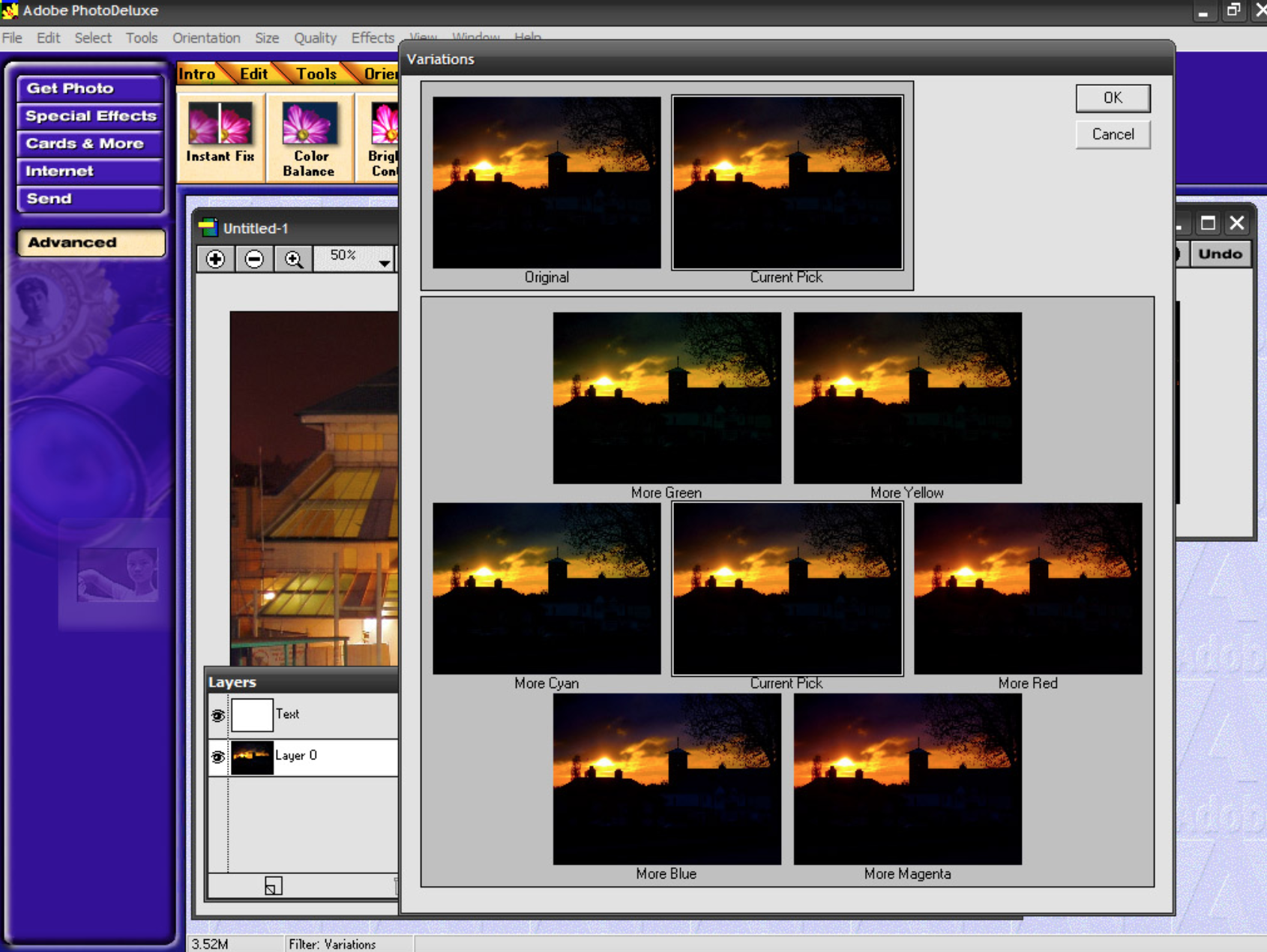

1996: Adobe released PhotoDeluxe as an “easier to use” version of Photoshop under the direction of Chizen. Within two years, it became the number one consumer photo editor and helped prove to the rest of the company that consumer products could gain popularity. It grew so quickly in popularity because Adobe bundled it really well with their other image editing software, making it really attractive to consumers.

Adobe PhotoDeluxe [Source]

1997: Adobe was making $917 million in annual revenue. Eighty percent of that was coming from applications. Much of the success of these applications can be attributed to Adobe creating some of the first desktop-accessible applications for graphic image editing. And even when they weren’t first-to-market, they had the advantage of bundling their products with the many other useful tools in their suite.

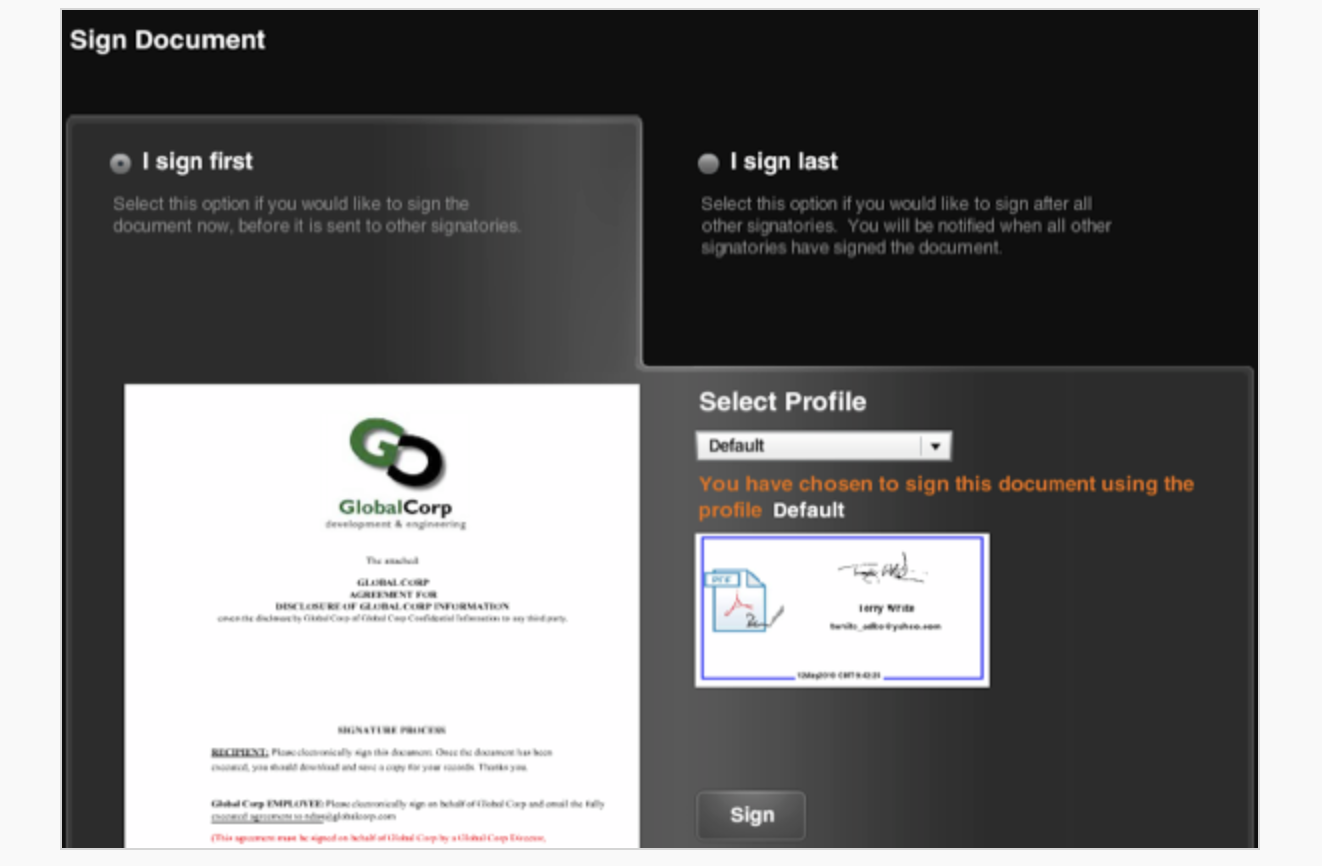

1999: Adobe released Acrobat 4.0, an important set of updates and feature additions that skyrocketed sales for corporate users. New features like password protection, digital signatures, and the ability to collaboratively annotate and review were great for business use cases. These additions led to more sales with the lucrative corporate audience. Adobe’s product stood out in particular over competitors because it introduced the ability to capture web pages as PDFs, which was revolutionary in the industry. Because these improvements made Acrobat 4.0 so attractive to corporate users, revenue from this product line alone more than doubled from the previous year ($58 million to $129 million).

2000: Thanks to Bruce Chizen’s work as the head of the new Consumer Products Division at Adobe, other leadership had started taking note of his vision and respected his opinion. In 1998, he was promoted to executive VP, where he worked closely with the co-founders to lead the company. Then, when Geschke retired in 2000, Chizen was named president. When CEO Warnock decided later that year that he wanted to spend more time with his family, Chizen was also made CEO. With his focus on building out products for new markets, Chizen would help to turn Adobe from a design tool provider into a diverse software company.

2001-2002: Adobe released a page layout app called InDesign. This was a direct response to pressure from a competing company, Quark, to compete with their page layout app called QuarkXPress. InDesign was a more modern answer to PageMaker, which hadn’t been updated in almost a decade, and could show off the strength of Adobe’s other products. InDesign helped Adobe compete with Quark and win back their professional creative audience.

2003: Adobe bundled all of their products together in the Adobe Creative Suite to unify their branding and start tying their products together.

2005: Adobe acquired a competitor, Macromedia, and all of their flagship products. The notable ones were an easier-to-use Photoshop competitor called Dreamweaver and a platform for animations and video players called Flash. This gave Adobe even bigger market share in consumer markets because of the users that these products already attracted.

Macromedia attracted designers who were particularly interested in web graphics. Acquiring this competitor was a step in the right direction for Adobe given the growing prominence of the Web, although they still weren’t throwing their weight behind web applications. For years, the company incorrectly brushed off the Internet as a phase.

As all of Adobe’s products became more mainstream and easy-to-use, they gained popularity in non-professional, consumer markets. Consumers even started pirating the software. Though this didn’t generate revenue for Adobe, it familiarized curious consumers with their products.

Simultaneously gaining more turf in consumer markets and on the web broadened Adobe’s market drastically. This gave them the leeway to experiment with their business model and consider one that made more sense for web applications than licenses. This set Adobe up to make a difficult move: from traditional software to the cloud.

2007-2017: Movement to a Cloud-Based SaaS Company

“We always had the right motivation, which is: How can we innovate at a faster pace? How can we aggressively acquire new customers and how can we continue to build a more predictable and recurring revenue stream?” – Shantanu Narayen, Adobe CEO, on why they moved Adobe to the cloud

For over two decades, Adobe was able to stay competitive as a license-based company. They’d built a strong brand identity as a provider of powerful professional and consumer design tools that people were willing to pay a high price for upfront.

But when you’ve been around for a few decades, you see a lot of changes in an industry—and the software industry was changing yet again. Instead of selling software through licenses and on CDs, many companies were starting to sell software over the cloud on a subscription plan. In 2007, global revenue from SaaS enterprise apps was around $5.1 billion, and was predicted to grow over 100% over the course of the next few years.

To survive, Adobe would have to unlock the subscription model, too. Selling software licenses upfront was less reliable as CD-ROMs became antiquated in the eyes of the software industry. Subscription revenue was more predictable and could be sustained or increased over time to ensure financial security.

Moving to the cloud also presented opportunities for Adobe to protect itself against competing products. With more design tool competitors (like InVision and UXPin) and point solutions (like Sketch) available on cloud-based subscription plans, users could try out Adobe competitors with very little risk. These cloud-based solutions could also roll out updates and improvements whenever they needed to, as opposed to Adobe’s 18-24 month cycle of product releases. All of these factors weakened the lock-in that Adobe previously had with their users.

There were also strategic advantages to moving to the cloud. According to Mark Garrett, Adobe’s CFO, Adobe users had more creative demands but the creative business wasn’t growing much—their unit sales were pretty flat. Adobe was primarily growing revenue by raising prices, which they knew wasn’t sustainable in the long-term.

But even though a move to a subscription-based cloud service seemed like it made sense for Adobe’s future, this business model wasn’t the most natural fit for Adobe’s products or users. Many users relied on Adobe products to do their jobs, and a subscription model was seen as less stable than outright ownership of the software because users believed that their usage and access could be abruptly interrupted or cut off. Providing the software over the cloud raised issues of whether people would be able to access their work on the road, and whether downloads or buggy updates would set back their work.

On the business side, moving to the cloud was also an instance of Adobe looking to the future and making a long-term decision at the price of short-term reward. Transitioning from licensed software to cloud SaaS is a difficult, expensive, multi-year process. Even though the decision was brilliant in retrospect, it was difficult to commit that much money and work toward a move like this at the time. Many of Adobe’s senior leaders were concerned about the risks of revenue, earnings, and stock prices dropping in the transition period. They were nervous that both customers and shareholders wouldn’t understand why they made the switch, would lose faith in the company’s success, and that company financials would tank beyond recovery.

After a lot of planning and modeling, the team realized that the potential rewards hugely outweighed the risks. The final straw was the recession in 2008 and 2009, when Adobe realized that they had very little financial barrier and needed to make this move to protect their company and customers. They fully committed to making the risky move, worked through their concerns, and successfully transitioned into a cloud SaaS company.

Here’s a closer look at how they did that:

2007: Shantanu Narayen took over as Adobe’s CEO, which marked a turning point for the company. Narayen came in with a vision to disrupt the status quo at Adobe and build out more digital media and marketing services to aggressively expand usage. While Bruce Chizen’s legacy was in helping Adobe transform into a diverse, multi-product software company, Narayen’s legacy has been successfully transitioning Adobe into a full-service enterprise cloud provider.

2008: Adobe released a webtop version of Photoshop called Photoshop Express. This was designed as a consumer product to be really easy to learn and use, allowing users to make edits to photos, create albums, and share them with others. This demonstrated that Adobe was taking a big step towards embracing the internet by creating a consumer-facing web product that took advantage of the web’s social network capabilities.

2009: Adobe acquired the top enterprise analytics company Omniture. This was important because it allowed Adobe to offer web analytics, measurement, and optimization technologies to Adobe product users directly in their workflow. It opened up a new category of products—analytics—and introduced new customers—marketers. The analytics and marketing segment was conveniently adjacent to their existing creative design market. Now, new types of users who needed to evaluate the performance of designs on the web could have easy access to analytics tools. This helped them measure the effectiveness of creative campaigns built with Adobe’s other tools. When Adobe purchased Omniture, they said, “We’re going to be the Big Data company for marketers.”

2010: Adobe released eSignatures, a cloud-based signature tool that demonstrated the company was taking more steps toward building for the cloud. When they released the tool, they said that the mission behind it was to build “something that was easy to use, fast, accessible to anyone with an internet connection and a browser, and that wasn’t overloaded with complicated features.”

2011: Adobe announced that it would leave Flash behind after it was rejected by Apple and mobile. Instead, they made plans to focus more on HTML5—which the rest of the tech industry was doing, as well—to give them more of an opportunity on web and mobile browsers. This was an important flashpoint because it became clear that within the complex tech ecosystem, software companies needed to adjust around hardware companies. It also set Adobe in a direction to prioritize compatibility on the Web.

2013: This was the biggest turning point in Adobe’s history. Adobe released Creative Cloud (CC) to take the place of the Creative Suite. They announced that all future versions of their Creative Suite apps would only be available for purchase through a subscription-based service, and only available on the cloud. Their service went from a one-time purchase of $1800 to $50/mo for the entire CC (or $19/mo for a single app).

Adobe’s move to the cloud has since been called the textbook example of how companies should make the transition. They were ultimately successful because they did a few things exceptionally well:

- The company made sure to offer valuable use cases for the many different types of users and projects they supported (like designers, photographers, videographers) and add new features to the cloud-based tools

- They shifted their entire business perspective to cater to the digital workplace

- They broadened their target market beyond creatives to sell to more members of the C-Suite

The company’s financials have definitely reflected their success. SaaS businesses have higher valuations than licensing companies, and Adobe has seen their share price and valuation increase over the last several years.

Now, Adobe is still growing their top and bottom line thanks to their cloud subscription services. Recurring revenue from subscriptions represented 86% of the company’s total revenue in 2017 of $7.3 billion. The 35-year-old company is growing revenue 25% YoY, and their stock increased 20% a few weeks ago in reaction to a strong forecast for FY18.

Even among the world’s biggest software companies, Adobe is growing quickly in comparison. Five years ago Adobe and Salesforce were both $40 stocks—now Salesforce is ~$107 and Adobe is ~$183. It’s exciting to think about what’s next for them.

Where Adobe Can Go From Here

Adobe needs to keep up the momentum of broadening their customer base and supporting company-wide business. This is how they can continue transitioning out of their last-era mindset.

Adobe can continue growing by acquiring other excellent design and optimization analytics tools and incorporating them into their existing suite of products:

Acquire more UX/design tools: To keep winning in this space, Adobe needs to acquire other UX tools, such as InVision. Tools like this are more focused on web and mobile app design than Adobe’s traditional suite of products. InVision’s Studio, which they’ve positioned to be a Photoshop competitor, is specifically designed for the “modern design workflow” with advanced animation and responsive design features. It’s extremely user-friendly and has a lot of potential use cases, like presentations, collaborative workflow design, and project management. InVision also has plans to expand even further and release an app store. If Adobe were to acquire InVision, they’d not only knock out the threat of competition, but also widen the top of their funnel with a strong product addition.

Provide more point solution tools: Point solutions, like the digital design toolkit Sketch, are for extremely lightweight use cases. Sketch has been described as “a reductionist version of Photoshop, baked down to just what you need to draw stuff on a screen.” A point solution like this works well with the subscription billing service that Adobe has been transitioning to because it allows companies to try out lightweight products. Adobe could acquire point solution tools like Sketch—or they could continue building out point cloud solutions like eSignature. Giving users more ways to try out small slices of the Adobe suite—in a commitment-free way, with a subscription plan—could help attract people who were never before interested in Adobe’s powerful, but expensive and complex, tools.

Acquire next generation analytics companies: The analytics space is adjacent to web design. Adobe has already taken a stab into this field by acquiring Omniture, but they have potential to expand even more with a greater range of tools if they acquire other forward-thinking analytics companies. For example, a company like Amplitude focuses on features that help people understand user behavior, ship iterations quickly, and measure results. This would be a perfect complement to Adobe’s web design tools. It would help designers who are already using Adobe products, and attract analysts and product marketers who work alongside the designers.

Adobe’s company journey has gone through many different stages, but through it all, they’ve focused on delivering quality products to a core audience and then expanding outward to adjacent spaces. Their future success will rely on them continuing to iterate and deliver these products to growing markets in the new SaaS landscape.

3 Key Lessons Companies Can Learn from Adobe

Not many tech companies can say that they’ve been around for as long as Adobe—or that they’re still successfully innovating and growing. Adobe’s journey is unique and has been largely shaped by how they’ve navigated multiple shifts in the industry.

But SaaS companies getting started today can still learn a lot from Adobe’s journey. Here are the three main lessons we can learn from Adobe:

1. Expand to naturally adjacent spaces

Adobe has built best-in-class products for designers. But as they’ve grown, they’ve made really smart choices about the new markets they’re targeting. Their key decision has been to go after markets that are naturally adjacent to the designer market—like marketing and, more recently, analytics.

Companies that want to expand to new markets also have to be thoughtful about how the new markets relate to their current market. By moving to an adjacent space, you have the potential to capture new users while also providing new value to existing users. This also helps a company grow without straying too far from their core vision.

Whenever you’re looking to add a product and/or target a new market, you need to validate your idea in that market. I have a three-step process that I use to validate ideas:

- Create a problem hypothesis from your idea

- Set up a system to pull people to you

- Find the pattern of pain

A great thing about targeting an adjacent market is that it gives you the option of validating a new idea with potential users. You can do it through surveys and open forums, as well as with tools like User Testing. Whatever you do, make sure the new product or service you’re considering really is a natural expansion from your existing offerings.

2. Be intentional with capital and think about financials in the long-term

Over the last 35 years, Adobe made some really smart financial decisions. They’ve used capital from product growth and their IPO to make key acquisitions, which added more streams of revenue. They’ve funded research and development to build out new products and widen customer acquisition. This process of using revenue to add more products that generate even more revenue created a virtuous cycle.

Adobe’s winning strategy was being intentional from the beginning and thinking long-term. Their very first product, PostScript, was a huge success, and there was no need for Adobe to add more revenue streams at that time. But the leadership knew that remaining a one-product company wasn’t a smart financial decision in the long-term. That’s why they started building out apps that could target new users and bolster PostScript’s revenue, even though they weren’t immediate cash cows.

I’ve told companies before that the early decisions you make around finances and business models have teeth later on. To make sure your early decisions don’t come back to bite you, there are some important points you have to consider early on:

- Are we planning on building a single product, or do we have plans to build more? What is our contingency plan if our first product fails?

- How do we want to sell to our customers, and what do we want to charge? Will the prices encourage some users and prohibit others? Are the users we’re attracting the ones that will help us grow?

Of course, every company has to troubleshoot unexpected situations and make financial decisions that they never anticipated along the way. But don’t shoot yourself in the foot right away—make early decisions that set you up for long-term success.

3. Make acquisitions based on product gaps, talent gaps, and the competitive landscape

There are many reasons why one company would acquire another. Adobe has been successful by making smart choices about what needs they’re looking to fill and what will push them forward at a given moment in time.

Some of Adobe’s acquisitions, like Omniture, gave Adobe the ability to add a completely new set of tools into their product offerings. Others, like the Aldus acquisition, doubled the size of the team and brought in talent like Bruce Chizen who went on to have a huge impact at Adobe. Meanwhile, the Macromedia acquisition helped Adobe to take a competitor off the map and end a crash course where the two companies were set to collide.

A smart, thoughtful acquisition happens when a company is in tune with what it’s missing and what its market/industry is demanding. On a high level, this means that the leadership of the company should be aware of three main problem areas:

- Product gaps

- Talent gaps

- Pressure from competition

On a tactical level, being aware of product gaps and pressure from competition means being in touch with customers and their workflows, and doing market research to know what other options they have. Becoming aware of talent gaps means running internal surveys to fully understand how teams are functioning and where team members need more support.

You can only fill the gaps when you know where the problems are. Make sure you take the steps to build this internal and external company awareness among your leadership.

Thirty-five years and counting

Adobe’s story is a journey of transformation. They’ve seen different eras in software and are doing what they can to be successful in this new one. So far, they’re doing a great job. It’s only possible to continue growing and thriving like they have by making hard long-term decisions and being really intentional about how they can expand and bring new value to customers.

They still have so much potential—and I’m excited to see what the company does next.