How Spotify Built a $20 Billion Business by Changing How People Listen to Music

In 2006, the landscape of the music industry was very different from what it is today. Peer-to-peer music sharing service Napster was long dead and buried, having been hunted to extinction by the Recording Industry Association of America’s lawyers. Internet radio was still in its infancy; it would be two more years before iHeartRadio and Pandora launched their respective online radio stations. Even the music industry itself was struggling: Sales of physical media such as CDs had fallen consistently for the past several years, and the record labels themselves seemed to have few ideas.

For Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, two Swedish serial entrepreneurs, this presented an incredible opportunity. Convinced that there must be a better way for people to find and listen to new music, the two men began brainstorming ideas for their next business venture.

That business was Spotify.

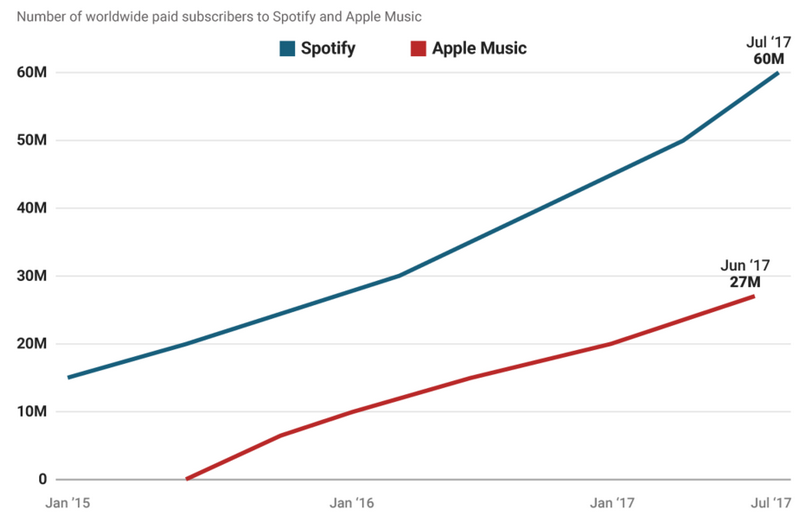

Spotify has since become the most popular streaming music service, boasting more than 70M paid subscribers. But how did they get there, and why did Spotify strike such a powerful chord with music fans?

The secret behind Spotify’s success is that the company identified a huge opportunity among music consumers, and then worked harder than any other company to reach product-market fit first. Napster laid the groundwork for Spotify’s success by introducing a new way to listen to music without the limitations of physical media or ownership. What made Spotify such a bold, ambitious idea was doing the same thing Napster did—but legally.

Let’s take a closer look at:

- How Spotify’s relentless focus allowed the company to reach product-market fit before anyone else in the streaming music space

- How Spotify leveraged virality in its sign-up process to ramp up early growth quickly

- How Spotify was able to negotiate crucial licensing agreements with record labels very early on in the company’s development—and why these deals were pivotal to Spotify’s survival

- Why Spotify’s freemium model is a major competitive advantage for the company in a crowded, increasingly competitive space

Spotify may be one of the music industry’s biggest and most influential players now, but the company’s early years were spent focusing intently on one thing: the race to reach product-market fit.

2006–2010: From the Ashes of Napster to Product-Market Fit

Like many of the best business ideas, Spotify was born out of frustration and personal experience.

Ek and Lorentzon spent hours hanging out in Ek’s apartment in a suburb of Stockholm as they brainstormed ideas for their new business venture. As they worked, the two friends relied on Ek’s multimedia PC as an entertainment center and music player. However, Ek and Lorentzon soon grew frustrated with the limitations of finding and listening to music using a computer.

That’s when they came up with the idea for what would become Spotify.

“We pretty much spent all of the autumn just discussing a ton of ideas. I remember however that we sat around my media htpc machine quite a lot and thought that it was cumbersome to get content, despite the technology having been around since at least 2000. I think that’s why we got stuck on the idea of Spotify.” – Daniel Ek

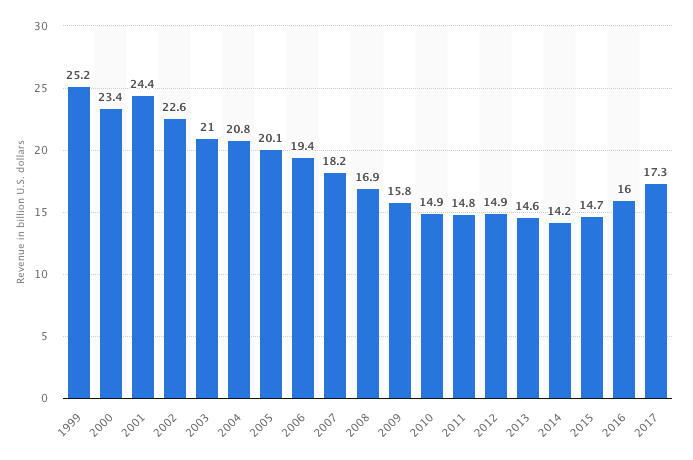

When Ek and Lorentzon began brainstorming ideas back in 2006, the music industry was in a crucial state of flux. Sean Parker’s failed peer-to-peer music sharing service Napster had been wildly popular with music fans, but had made powerful enemies in the recording industry by essentially facilitating wide-scale copyright infringement through music piracy. By 2006, revenue had fallen from $25.2B in 1999 to $19.4B.

The real brilliance of Spotify’s early approach is that it identified and carved out a niche between two extremes in the music market. At one end was Napster, which was hugely popular but illegal. At the other was Apple’s iTunes, which sold songs individually for as much as $2 per track. The vast gulf between these two extremes is where Spotify would succeed.

Initially, Ek and Lorentzon explored the idea of developing a peer-to-peer music-sharing service like Napster. But it quickly became apparent that piracy had limitations beyond its illegality. It took several minutes to download a single song. The audio quality of pirated tracks varied wildly. Even popular torrents were infested with viruses and malware. But despite the many problems with piracy, Ek believed people didn’t set out to become music pirates. He believed that music fans just wanted a better music discovery and listening experience.

“I just really believe that if we create the right product, which is better than piracy, that people will come.” – Daniel Ek

What made Spotify so brilliant was that it fundamentally improved on the Napster experience in every way. Spotify would deliver music instantly, with high-quality audio, no downloads, and completely legally. To realize their ambitious vision, though, Ek and Lorentzon would have to invest heavily in engineering to nail down every aspect of Spotify’s user experience. Competing with piracy at one end of the spectrum and ownership of physical media at the other, Ek and Lorentzon knew that nailing their product was fundamental to Spotify’s success.

Development of Spotify’s initial product, which was known as Spotify AB, began in Sweden in 2006. The company built a working prototype in just four months. Less than a year later, in 2007, Spotify AB went into closed beta.

Ek’s vision for Spotify was to create a seamless listening experience. To accomplish this, Ek’s engineering team worked tirelessly to patch together a functional prototype of Spotify AB as quickly as they could. But as focused as Spotify was on reaching minimum viable product, Ek was obsessed with making Spotify AB as technically lightweight and responsive as possible. The human brain perceives anything less than 250 milliseconds as instant, and Ek wanted Spotify users to feel as though they had every single song ever recorded right on their hard drives.

However, Ek’s obsession with technical excellence was about more than just the user experience. The frictionless experience of using Spotify was the service’s primary competitive advantage. For Ek, the only way to compete with free music was to make the experience of using Spotify so good that users would happily pay $10 per month even though they could easily download torrents of their favorite music for free.

“We spent an insane amount of time focusing on latency when no one cared because we were hell bent on making it feel like you had all the world’s music on your hard drive. Obsessing over small details can sometimes make all the difference. That’s what I believe is the biggest misunderstanding about the minimum viable product concept. That is the V in the MVP.” – Daniel Ek

To find its initial users, Spotify contacted influential music bloggers in Sweden, inviting them to try the new product. This strategy was incredibly effective. Spotify’s beta testers were struck by just how good the company’s product was, even at such an early stage in its development. In just one year, Spotify had built a product that music bloggers were already excited about — and they helped spread the word about the exciting new music app.

“Even today, Spotify’s traditional music player is better than everything I’ve tested on this side of Winamp / iTunes and a really good Direct Connect hub.” – Henrik Torstensson

Having raised more than $85M in just two years as part of its Series A and B rounds, Spotify invested much of its early-round funding into hiring top engineering talent. Spotify didn’t even have to look particularly hard to find skilled technical talent. Word of an exciting new music app out of Sweden had spread quickly among tech circles, and the company went on a hiring spree to keep up with product development.

“They had a level of ambition that I hadn’t seen before in Sweden and were very aware of what they were building. They weren’t settling for the good enough; they were going for the best. They were looking for the best people, the best talent and were not easily impressed by the regular VC giants.” – Pär-Jörgen Pärson

As the Spotify team grew, so did their scale on the business side. While many startups believe the only way to grow is to scale quickly, Spotify chose to focus on developing a solid product and growing slowly by restricting how many invites users could give away to their friends. This allowed Spotify to maintain its focus on product development; plan for and manage steady, gradual user growth; and create an air of exclusivity around the product itself.

With the broader music industry in decline and a strong understanding of the market, Spotify’s timing was perfect. The company was able to leverage this timing and market knowledge to negotiate its crucial early licensing deals.

By the time Spotify launched in Sweden in 2008, global music industry revenues had fallen to $16.9B, and the steady decline showed no sign of slowing down. With sales dwindling and few ideas on how to stop it, the “Big Four” American record labels—EMI, Sony, Universal, and Warner Music—and a couple of smaller labels agreed to make their entire back catalogs available to Ek and his company for use outside the U.S. on a limited basis. In return, the Big Four record labels became Spotify’s biggest shareholders, receiving almost one-fifth of Spotify’s stock for just 100,000 Swedish krona (approx. $112,000).

Ek had little trouble selling the label executives on his idea, even without the sweetheart stock deal. After a demonstration of the Spotify product in London in 2008, Universal Music Sweden’s Per Sundin was blown away, as were several other label execs who were present at the demo.

“This can’t be true. It can’t be this good.” – Per Sundin, Universal Music Sweden

It’s difficult to overstate just how pivotal this initial agreement between Spotify and the Big Four labels was. Without that first deal with the labels, Spotify wouldn’t have survived. It’s no coincidence that Ek announced the licensing agreements with the majors and the official launch of Spotify in the same blog post. Spotify needed the labels—and their back catalogs—as much as the labels needed a new way to reach young music fans.

The record labels themselves had little to lose by backing Ek’s experiment. With sales and revenue down, the labels needed to try something. If Ek’s product didn’t take off, the labels wouldn’t have been any worse off than they were to begin with.The biggest loss they would suffer would be losing what little money the labels had paid to become Spotify’s biggest shareholders when they signed over their back catalogues.

More importantly, the legacy record labels simply had no idea how people consumed and shared digital music. The major labels were so preoccupied with the decline of CD sales that they couldn’t see the opportunity for digital music distribution that was staring them in the face. Napster might have been able to leverage similar deals, but the labels saw Napster as an existential threat, not a potential partner. The labels sued, and the rest is history.

“[The record labels] were pretty frank about how no way, no how were they going to scare off traditional retail. They thought, We do a deal with Napster, we won’t be able to distribute to Tower Records anymore. Now you can see that worrying about alienating Tower Records was a shortsighted concern.” – Elizabeth Brooks, former VP of Marketing, Napster

The second major event that shaped Spotify’s growth during its formative years came in 2009, when early Facebook investor and Napster founder Sean Parker wrote what WIRED described as a “1,700-word love letter” to Spotify.

In August 2009, Parker emailed Ek to voice his support for the growing company after discovering the product just a few weeks earlier. Like the label execs before him, Parker was amazed by how solid Ek’s product was, even at that early stage. Parker was particularly impressed with Spotify’s user interface and its social sharing functionality that allowed users to create and share playlists of songs with friends.

“Napster was my first attempt at building a company, and one of my early attempts at building a usable product. While I’m proud of the impact we had, I’m not particularly proud of the interface we built, nor of the design/aesthetics of the product. You have surpassed the product experience we built at Napster in all of these ways.” – Sean Parker

Parker was so taken with Spotify’s early product that he introduced a friend to Spotify. That friend was Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who was similarly impressed by Ek’s product. Parker’s intervention would later lead to the official integration of Spotify into Facebook — a partnership that would propel Spotify to new heights of growth when it launched in the United States.

Before that, however, Spotify needed to make its way across the Atlantic from Europe.

2011–2014: The European Invasion

By 2011, Spotify had more than 10 million tracks in its catalog, more than 1M music fans using its service across seven European countries, and more than $100M in its bank account. Spotify had built its freemium growth engine, but it needed more users to power it — and it would find them in America.

To bring Spotify to the U.S., the company partnered with some of America’s biggest brands, including Chevrolet, Coca-Cola, Motorola, Reebok, and Sprite, among others. What was particularly clever about this approach wasn’t partnering with major advertisers. It was how Spotify leveraged the same growth strategy in had used in Europe. Spotify ran display ads for its American launch partners on its freemium product. In exchange, the American advertisers gave away exclusive Spotify invitations to their social audiences. This drove traffic and brand awareness for the advertisers, staggered Spotify’s initial growth in the U.S. by releasing invitations to the service in limited volumes, and retained the exclusivity that generated much of the buzz surrounding Spotify by not making it available to everyone right away.

When Spotify finally made it to the United States, its freemium, ad-supported product looked a lot like the Spotify we know and love today. Freemium users could access millions of songs, share playlists with friends, and play local music files through the Spotify app. Spotify’s freemium version had its limitations, but it was still an intuitive, rewarding app that delivered the optimal music listening experience Ek had envisioned years before.

There were, however, just enough inconveniences with Spotify’s freemium product to make its now-defunct Unlimited tier (a short-lived subscription tier exclusively for desktop that Spotify retired in 2013 due to rapid growth in mobile) and its Premium subscription tier very attractive to hardcore audiophiles. For one, freemium users could only listen to 20 hours of music per month for the first six months, after which this was reduced to just 10 hours per month. Finally, freemium users couldn’t listen to the same track more than five times.

Spotify’s Premium subscription, on the other hand, eliminated the friction of the freemium app. Not only were there no ads on Spotify Premium, there were no listening limits, either. Premium users could listen to music in Offline Mode, a feature that was introduced shortly before Spotify’s launch in the U.S., and play tracks on their mobile devices—a significant differentiator at that time.

This period would prove to be a crucial growth stage for Spotify as a product. By now, Spotify had spent much of its time and focus scaling. It had built its platform and secured its content. Now, it needed more users. Without access to the American market, Spotify couldn’t hope to scale significantly. However, once again, licensing deals threatened to stop Spotify in its tracks.

Spotify had originally planned its U.S. launch for 2010. However, complications in negotiations with the major labels forced Spotify to push back its launch date. In December 2010, news media began reporting that Spotify had yet to sign a single deal with any of the Big Four labels. At the heart of the disagreement were two big problems the labels had with Spotify: its business model and its conversion rates.

Spotify had long maintained that its freemium product was crucial to the company’s continued growth. The Big Four, however, wanted Spotify to launch in the States with a purely paid subscription model. It’s important to note that the Big Four record labels in the U.S. weren’t opposed to Spotify on principle. Far from it, in fact. The major American labels had watched helplessly as iTunes rose in popularity virtually uncontested, and they desperately wanted to get behind a platform that could effectively compete with Apple. However, the second point of contention between Spotify and the majors was the company’s conversion rate.

In 2010, it was reported that Spotify’s conversion rate was approximately 7%. That was seen as too low for the Big Four, which wanted Spotify’s conversion rate to be somewhere between 15% and 20%. Although understandable, this is another example of how out of touch the major labels were with digital in a broad sense. A conversion rate of 7% may have been “too low” for the labels, but a conversion rate of 7% for a freemium product is amazing.

When Dropbox hit 100M users in 2012, analysts remarked that Dropbox’s conversion rate of around 4% was solid for a company with a predominantly freemium user base. By comparison, Spotify’s conversion rate of 7% should have practically guaranteed the labels’ cooperation. For the labels to demand a conversion rate double or even triple that shows just how close Spotify was to stalling before it could reach the U.S. In the end the labels relented, but without their support, Spotify’s expansion to the U.S. may not have happened at all.

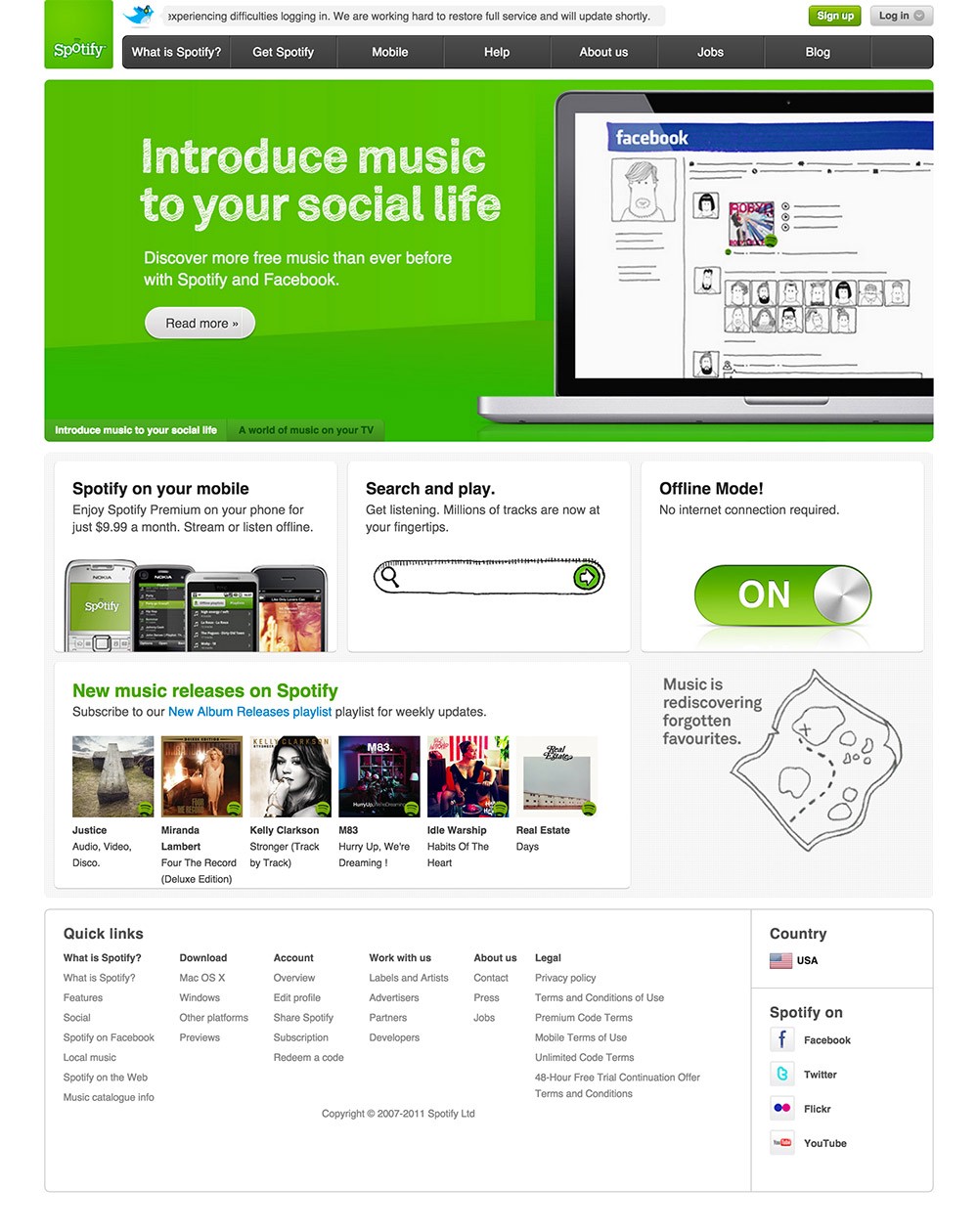

In 2011, While Ek and Spotify’s executive team played hardball with the labels, the company’s engineering teams continued to build product features that helped it grow and made its product stickier for users. The biggest such move during this period was when Spotify officially integrated with Facebook, becoming the official music player of the social network.

It’s not hyperbole to say that Spotify’s integration with Facebook was a pivotal moment for Ek’s company. However, the integration wasn’t just crucial to attract new users to Spotify—it was part of longer-term growth plans.

“You’ll now start seeing new music posts and play buttons all over your newsfeeds. Hit a play button and the music starts. Right there. Spotify fires up to give you a new soundtrack to your social life. Check out your new Music Dashboard and your real-time ticker to discover the music that’s trending with your friends.” – Daniel Ek

In the blog post announcing the integration, Ek noted that Spotify users who were active on Facebook listened to more music than Spotify users who weren’t on Facebook. Because these users are more social, Ek wrote, they’re more engaged and, as a result, more than twice as likely to pay for music—in Spotify’s case, by becoming paid subscribers.

This wasn’t the only aspect of Spotify’s integration with Facebook that was smart. Since the beginning, Ek had focused relentlessly on the experience of using Spotify. Ek understood that reducing friction in the sign-up process was critical to growing its user base. The Facebook integration eliminated friction from the sign-up process and made it literally effortless. With a single click or tap, Facebook users could create a free Spotify account in seconds. The integration with Facebook netted Spotify 1M new Facebook-connected users in just four days.

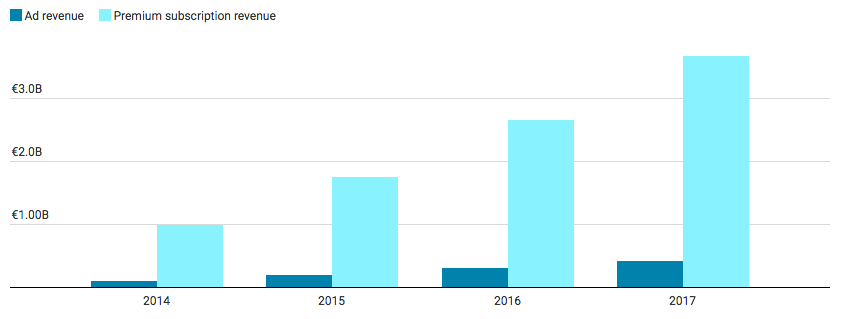

Although Spotify had managed its growth smartly by limiting the number of invites people could give away, adoption of Spotify’s premium subscription service had not kept pace with the growth in users of Spotify’s free product. To combat this, Spotify would spend much of this period refining its freemium offering to strengthen its pipeline from free to premium users. This was by necessity. Spotify’s free product was supported partially by advertising revenue (reports put Spotify’s ad revenue in 2011 at around $40M), but increasing ad revenue wasn’t a long-term growth goal. Ads kept the lights on, but the relatively low revenue from Spotify’s freemium ads meant it didn’t make sense for the company to further pursue ads as a separate revenue stream.

In 2012, Spotify raised $100M in its Series E round led by Goldman Sachs. This put Spotify’s total venture capital funding at that time at almost $300M. Although Spotify wisely decided against disclosing how it spent such a vast sum of money, it seems likely that the majority of Spotify’s VC funding was spent on royalties and its ongoing licensing deals with the major labels. In an interview with Business Insider, Spotify’s CFO Barry McCarthy revealed that after a user transitions from Spotify’s freemium tier to a Premium subscription, it takes Spotify approximately 12 months to recoup the costs of serving music to that user for free. Multiply this kind of loss by the roughly 5M paid subscribers Spotify had in 2012, and it becomes easier to see where that $300M went.

The following year in 2013, Spotify made mobile streaming – a formerly Premium-only feature – available to all users. Although it may have seemed counterintuitive for Spotify to suddenly start giving away Premium features, it made perfect sense. By 2013, Spotify had more than 6M paid subscribers, but it needed to increase this number dramatically to offset its considerable costs. Since Spotify had successfully leveraged its freemium product as a pipeline to paid subscriptions, making premium features available to its freemium users made Spotify’s free product even more alluring. Spotify would do the same thing again in 2014 when it eliminated time restrictions on all accounts worldwide, a move that made Spotify’s freemium product even better.

However, one of Spotify’s biggest challenges during this period was bridging the gap between its paid and free users. This challenge was particularly difficult because Spotify wasn’t just competing with other music apps and services—it was competing with any platform that offered music for free, including radio.

“Why link free and paid? Because the hardest thing about selling a music subscription is that most of our competition comes from the tons of free music available just about everywhere. Today, people listen to music in a wide variety of ways, but by far the three most popular ways are radio, YouTube, and piracy–all free.” – Daniel Ek

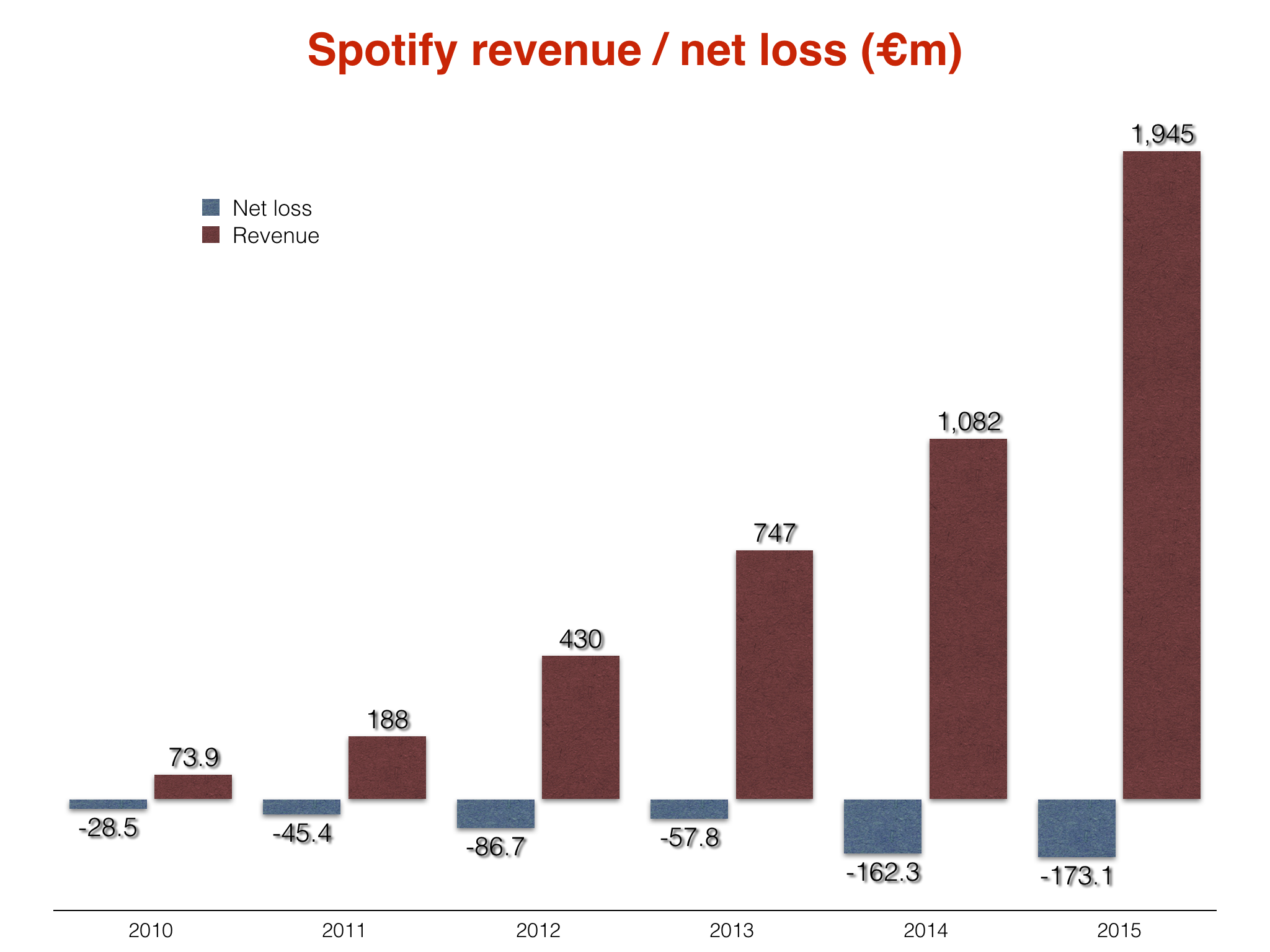

To complicate matters, the company’s financial outlook was mixed. As the number of Spotify users grew, so too did the company’s costs. Year-over-year revenue growth was strong, but the company’s annual losses mounted even as revenue increased. In 2014, Ek wrote in a blog post that Spotify had paid more than $2B in royalties to artists on his platform, revealing just how deeply Spotify’s operational costs were cutting.

Ek may have been keen to highlight how much money his company had paid in royalties to artists on his platform, but this figure revealed just how much money Spotify was paying to either artists or the record labels. Spotify’s costs were manageable for the time being and had helped Spotify achieve impressive growth in a short time. However, Ek would have to get his company’s costs under control if Spotify wanted to go public.

By the end of 2014, Spotify eventually going public had begun to seem increasingly likely despite the company’s stubbornly high costs. Spotify had more than 50M active users, of whom 12.5M were paying subscribers—the equivalent of a 25% conversion rate. By focusing on converting freemium users to paying subscribers, Spotify had grown revenue dramatically. To grow its user base, however, it would have to turn its attention back to its primary engine of subscriber growth, its freemium product. To accomplish this, Spotify did what it does best—making its freemium product even better by doubling down on developing new product features and making the Spotify experience even more engaging.

2015–Present: Personalization, Playlists, and Product

By 2015, Spotify’s popularity with music fans had made the company one of the music industry’s most powerful and influential players. The company continued to grow despite intensifying competition due to its relentless focus on delivering a truly optimal music experience. Spotify would leverage this momentum by introducing new features that would prove incredibly popular with users, such as algorithmically curated playlists and personalized recommendations.

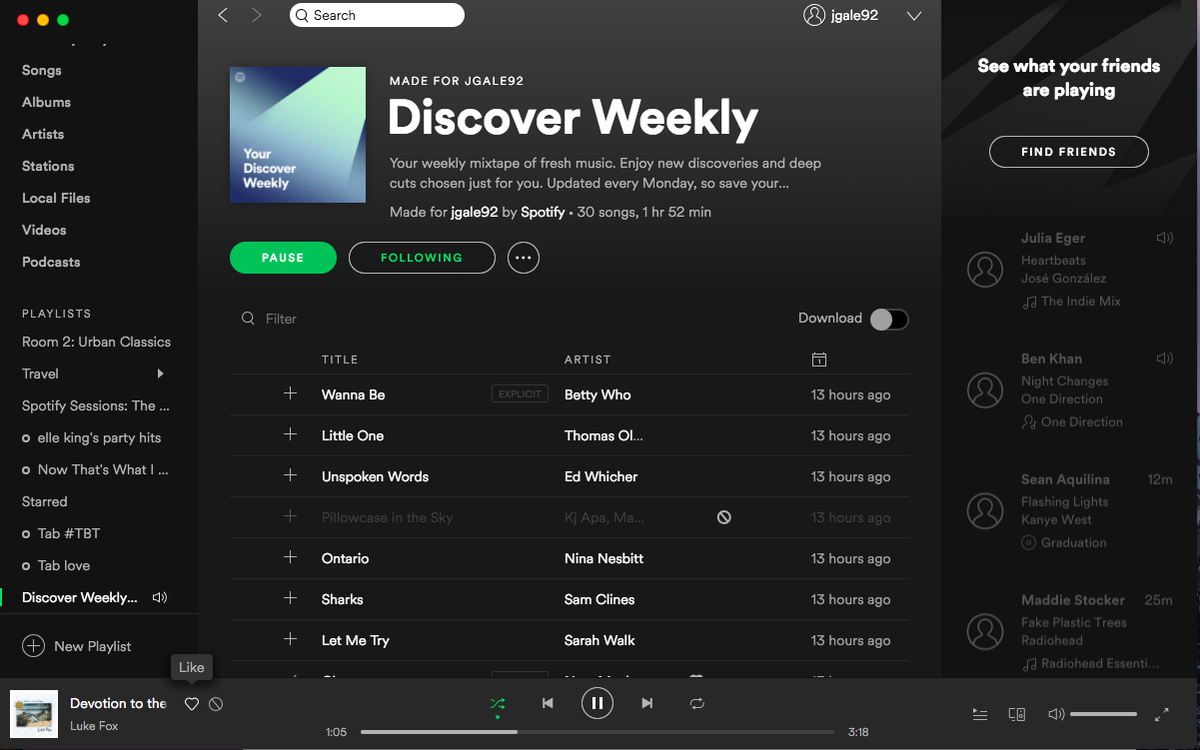

In July 2015, just weeks after raising $526M from 15 investors as part of its Series G round, Spotify introduced the first of its algorithmically curated playlist features, Discover Weekly. The feature, which curates a playlist of 30 songs for users every Monday based on their preferences and listening habits, was immediately and immensely popular with users.

Discover Weekly was so popular, it changed Spotify’s entire growth trajectory. Discover Weekly attracted 40M new users to the service, and more than 5B tracks have been streamed through the playlist feature. The response to Discover Weekly was so overwhelmingly positive that Spotify decided to invest more engineering resources into development of its algorithms and the infrastructure required to deploy similar internal projects. This would not only make the Spotify experience stickier, but more personal to each individual user.

“It’s created this Monday morning routine that was certainly never intended to the degree with which it’s taken hold of people—which is something we’re really inspired by and can learn from.” – Matt Ogle, Product Manager, Spotify

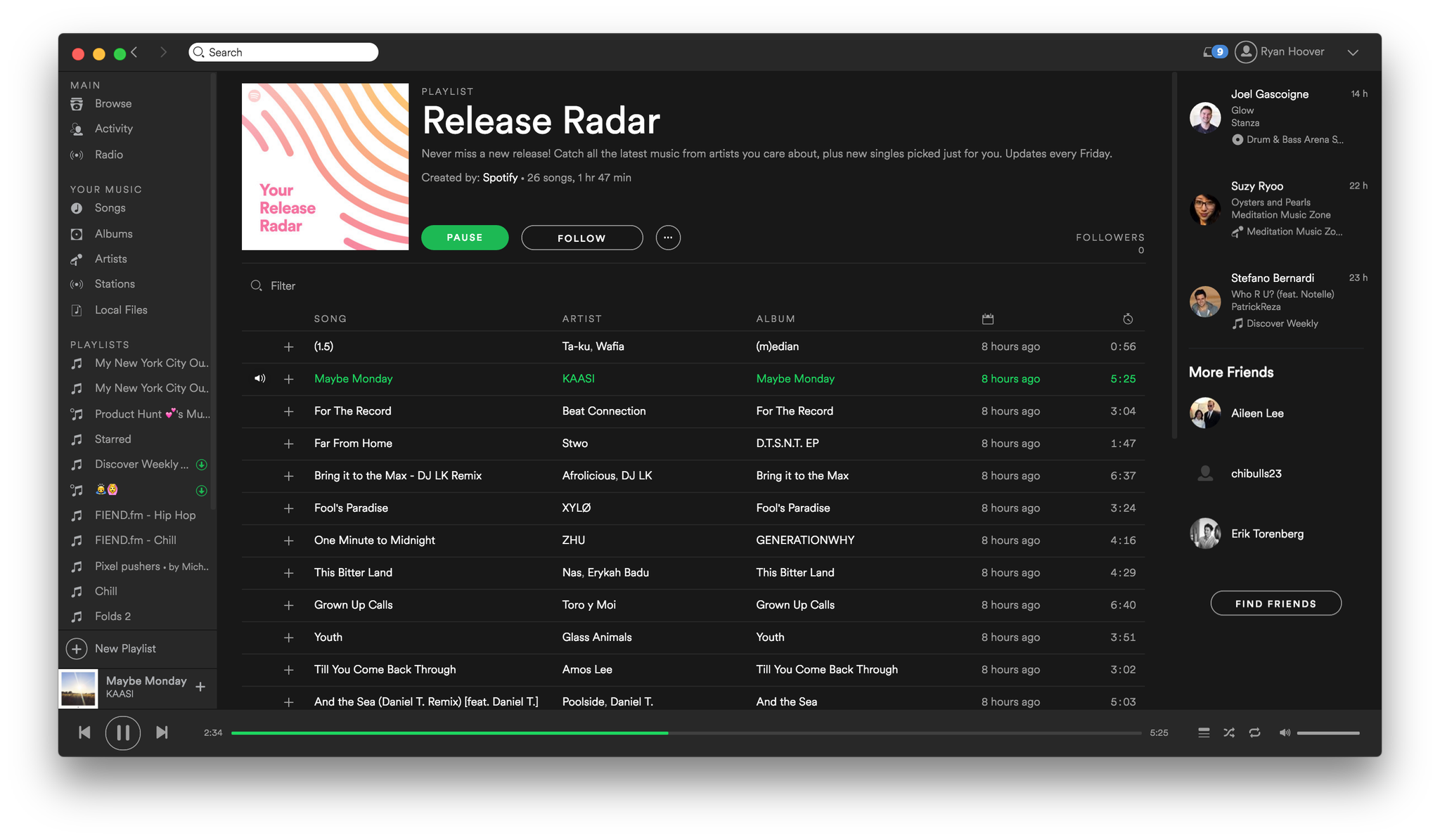

Discover Weekly was supposed to be just one new feature among many. Now, it had become a driving force behind Spotify’s broader engagement strategies. Galvanized by the success of Discover Weekly, Spotify introduced another algorithmic product feature in 2016, Release Radar. This algorithmically curated playlist is released every Friday and features roughly two hours of music from artists users are already following and listening to.

What’s really brilliant about Discover Weekly and Release Radar isn’t just the accuracy of the suggestions offered by the algorithmic playlists; it’s that Spotify has created two regular, weekly events that Spotify users not only enjoy but also actively look forward to. By bookending the beginning and the end of the week with new playlists, tracks, and artists, Spotify has effectively made itself an indispensable part of music fans’ entire week.

2017 saw the introduction of yet another personalization feature, Time Capsule, a playlist that compiles the top 30 nostalgic tracks from users’ teens and twenties. Time Capsule might not have the broad appeal of Spotify’s other algorithmic playlists – users have to be at least 16 years old and have listened to a sufficient number of songs on Spotify for the feature to work – but it’s another example of how Spotify has leveraged personalization to create an incredibly sticky experience, even with tens of millions of users.

While Spotify’s engineering team was busy creating new products like Time Capsule, the company’s business development team was no less busy. In August 2017, Spotify announced it had completed negotiations with Warner Music Group to renew its global licensing partnership with the label – the last hurdle Spotify had to clear before it could go public. Having finalized the last of its renewal agreements, Spotify was free to become a publicly traded company. On February 28, 2018, Spotify filed a direct listing on the New York Stock Exchange. Spotify formally went public on April 3.

It’s easy to forget that Spotify is a technology company in the truest sense. Discover Weekly, Release Radar, and Time Capsule show just how focused Spotify is on the core underlying technology behind its product. Spotify’s engineering team is now exploring several exciting new technologies to further improve its product, including deep learning techniques that analyze the waveforms of individual audio tracks, not just artist or album metadata, to make more intelligent and individualized recommendations. This is significant, as beyond pricing and the available catalog of music, there isn’t a great deal to differentiate Spotify from its closest competitors. It also demonstrates that Spotify has been uniquely capable of delivering greater personalization at scale.

Spotify’s labyrinthine licensing agreements with major labels might be of more interest to analysts and investors, but Spotify’s ability to consistently renegotiate licensing deals with the major labels is significant. The labels are heavily invested in Spotify and are strongly incentivized to help it succeed.

But for all its technological innovation and skill at the bargaining table, Spotify’s greatest challenge is achieving profitability. In its first earnings call since filing its direct listing, Spotify revealed it currently has more than 170M monthly active users worldwide, of whom 75M are paying subscribers. The company also disclosed that it generated approx. $1.36B in revenue in Q1 2018 – only slightly short of analysts’ forecasts.

Contrary to analyst assertions, Spotify’s unconventional IPO isn’t a problem for Spotify—only for Wall Street underwriters. The problem Spotify faces is how to reduce its costs in a meaningful way without damaging its core business model by upsetting the major labels. Analysts and investors have been patient with Spotify, but the social capital the company has built over the past several years won’t be enough to appease investors—Spotify has to reach profitability, and fast.

Where Spotify Could Go From Here

Despite not yet being profitable, Spotify is in a pretty enviable position. However, Spotify will need to think carefully about its next moves, especially regarding revenue. Where could Spotify go from here?

- Ancillary products. One of Spotify’s most urgent challenges is monetizing beyond subscriptions. Although paid subscriptions account for 90% of Spotify’s revenue, focusing on subscribers alone means that Spotify is confining itself to a single growth metric. One way Spotify could alleviate the pressure to grow its paid subscribers is by diversifying into ancillary products, such as ticket sales. This would be a challenging move for Spotify, given the dominance of established players, such as TicketMaster, but the strength of Spotify’s brand and its close relationships with major labels and independent artists could give Spotify an advantage in this area.

- Subscription price hikes. If the company is to succeed, Spotify has to increase its margins. The simplest way to accomplish this is to raise subscription prices. However, this approach is not without risk. Competition from Apple Music and Amazon Prime Music has put Spotify under significant pressure, and raising the price of its Premium subscription could alienate fans or result in higher subscriber churn.

- Acquisition of smaller companies. Although services such as SoundCloud are popular with fans, they pose little real threat to Spotify as a business. Companies like SoundCloud do represent a significant opportunity for Spotify to strategically acquire these smaller competitors to further expand its audience and its roster of independent artists.

- Launch its own record label/imprint. Given that the vast majority of Spotify’s operational costs are tied to record-label licensing deals and royalty payments to artists, it’s not inconceivable that Spotify could launch its own record label. This would be a strategically risky move, but it could have significant long-term potential, as it would eliminate at least some of the most considerable costs Spotify has as a business. The launch of its own label could also strengthen Spotify’s position as a champion of independent artists, which is a strong part of Spotify’s brand.

Lessons We Can Learn from Spotify

Spotify may have defied conventional wisdom throughout its growth, but there are plenty of actionable lessons to be learned from Spotify.

Focus on major market opportunities

Like Napster before it, Spotify was an ambitious idea and a huge gamble for Ek and Lorentzon, but the reward was worth the risk. Spotify succeeded because it identified a major market opportunity and pursued it relentlessly.

If you’re planning your next business venture, ask yourself some questions:

- How big is the potential market you’re targeting? Ek and Lorentzon had a bold idea, but the market they chose to target—music—was an immense opportunity.

- Who are the established players in your target market, and what do they do poorly? For Spotify, Napster proved that access to music was more important to fans than ownership of a physical record, but record labels’ failure to comprehend digital music distribution and a lack of competition allowed Spotify to flourish in a competitive market. Can you identify similar opportunities in your vertical?

- Have any other companies tried—and failed—to launch a similar idea to yours? For Napster, the timing just wasn’t right, and Napster’s loss was Spotify’s gain. Take a look at your industry. Have any other companies tried to do what you’re trying to do? Where did they go wrong? How could you avoid making similar missteps?

Ensure Business/Product Strategy Alignment

Even early versions of Spotify were impressive, but Spotify had to ensure alignment between its product strategy and its business strategy. This meant not only building a strong product but also ensuring that the licensing deals with the major labels were possible as well as realistically achievable. For Spotify, one could not succeed without the other.

Regardless of where you are in the product lifecycle, it’s vital to ensure that your product and business strategies align perfectly. Some questions you can ask to determine whether these two elements are aligned:

- Is your product development strategy dependent on business strategies that are beyond your control? Spotify had no idea if it could persuade the major labels to license their back catalogs to the company, even as Spotify’s engineering team was building the product. It’s vital that you be aware of potential bottlenecks over which you have little influence so that you can pivot if things go south.

- Do the expectations of your investors align with your product road map? Spotify faced bitter opposition when it wanted to retain its freemium tier as part of its expansion into the U.S. Are your investors truly onboard with your vision for the product?

- Can you identify partnership or integration opportunities that could help your business grow? Spotify’s early integration with Facebook, in 2011, was pivotal to the company’s expansion into the U.S. market. Can you leverage similar partnerships to grow your company?

Identify Potential Threats to Your Business — and Plan for Survival

Spotify’s relentless focus on building the very best possible product hasn’t just helped the company grow—it’s helped Spotify survive where lesser companies may have failed.

Ask yourself the following questions (and be honest):

- Is your product good enough to survive a shift in business model? Had Spotify failed to secure those first, crucial licensing agreements with the major labels, it may have been forced to reevaluate its entire business model. However, Spotify had such a good product that this may not have been as critical a blow to the company as it might sound. Is your product good enough to survive a dramatic shift in business model?

- Could a more established, entrenched competitor diversify its current offerings to encroach on your market? If so, would your company be able to respond effectively? If so, how? If not, why not?

- Is your target market big enough to support another growing company? For Spotify, music was a truly immense market opportunity. Even now, there is sufficient room in the market to allow for Apple Music, Spotify, and Amazon Prime Music to compete. Can your market realistically support another player?

Jukebox Heroes

Spotify has succeeded in spite of seemingly overwhelming odds not only because it’s free, but also because it’s a superior product. By making Spotify an intuitive, rewarding, and engaging experience, Spotify has capitalized on opportunities its competitors missed by combining the thrill of discovery, the excitement of sharing music with friends, and a vast catalog of every kind of music—all of which make Spotify a truly best-in-class product and a unique success story.