How Duolingo Built a $700 Million Company Without Charging Users

“We believe true equality is when spending more can’t buy you a better education.” – Duolingo founders

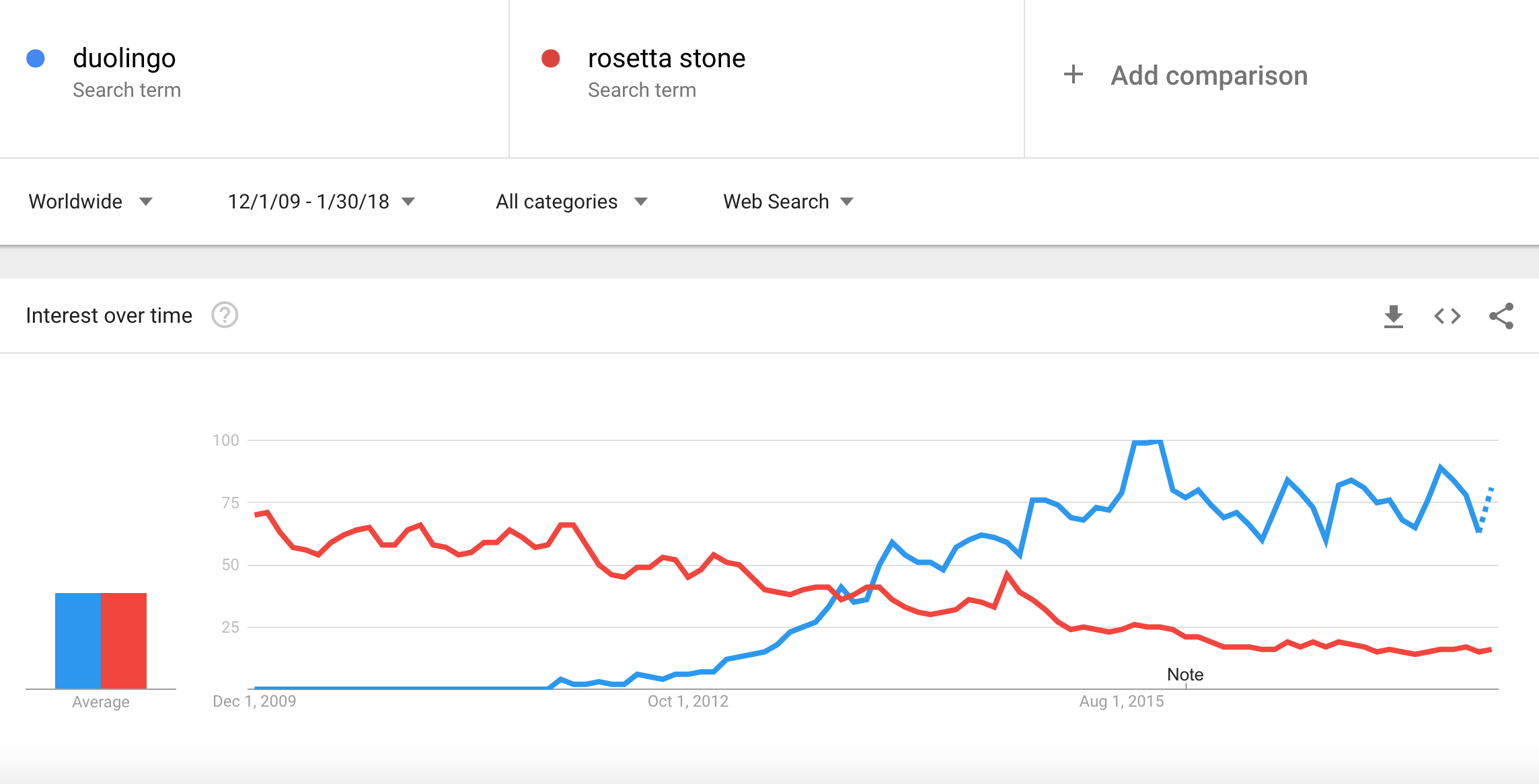

When the language learning software company Rosetta Stone went public in 2009, they raised $112.5 million on their first day of trading. They’d built a successful public company by going after a huge but fragmented market—worldwide language learners—and recorded over $209 million in annual revenue.

But the founders of language learning app Duolingo thought Rosetta Stone was capturing too small a market and growing based on a bad business model. Rosetta Stone was only targeting a tiny portion of the language learning market—and charging them a fortune. The Duolingo founders thought they had a better idea. And based on Google trends, it seems like a lot of the world now agrees with them.

The Duolingo founders identified a way to go after an even bigger market than Rosetta Stone’s. They wanted to tap into the hundreds of millions of people who wanted to learn a new language but couldn’t afford to shell out a ton of money for expensive software.

So Duolingo created a free app to help people around the world learn different languages. Currently, they have over 25 million monthly active users learning a language right from their web browser or smartphone, each at their own pace. Along the way, Duolingo has built a $700 million company—without charging users a cent.

There are two main things that helped Duolingo grow a huge, successful company while sticking close to their original vision: they went after a big market, and they meticulously experimented and used their data to inform all of their decisions.

Let’s take a closer look at the factors that have shaped Duolingo’s growth:

- Duolingo’s early business model around testing and crowdsourcing helped them to build a helpful app they could provide for free.

- The need to monetize prompted Duolingo to double down on their business translation services, and to further engage users to generate these translations.

- Duolingo refocused on their consumer use case and expanded their services around education, which led them to new monetization strategies.

Duolingo has constantly experimented with monetization, and at times they’ve even struggled with it. Even now, there’s no clear path forward for them. But Duolingo’s growth is a lesson in setting up the right conditions for experimentation. They built the processes and audience they needed to test things out and see what really worked best. They’ve been able to learn a lot about their business and their market along the way—and most importantly, they’ve created many business expansion options for themselves for the future.

Let’s dive in to see exactly what they did, and how any company can apply the same ideas.

2009 – 2012: Beta tests and crowdsourcing shape the early business model

Just when Rosetta Stone was being recognized as a successful public company, the Duolingo founders started working on a better way for the world to learn languages. Language learning wasn’t a new or revolutionary idea—but the way Duolingo wanted to approach the market was totally unprecedented.

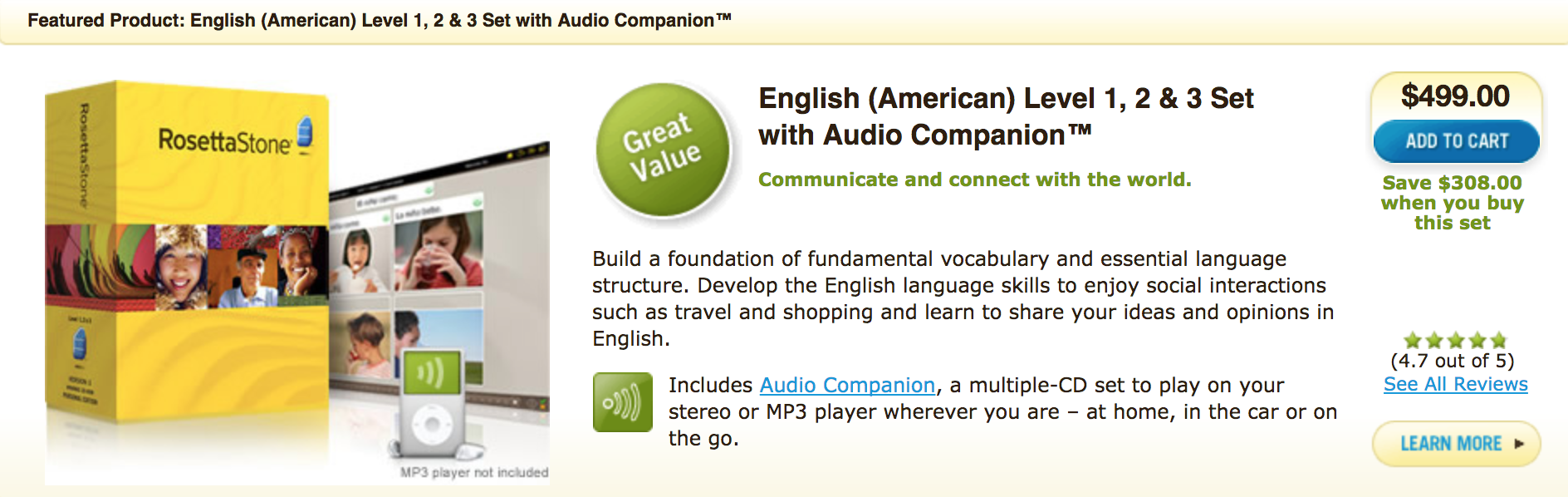

Before Duolingo, there was a huge cost barrier associated with learning a new language. Software like Rosetta Stone and Open English allowed users around the world to learn over 30 languages from their homes. The catch was that they had to pay a few hundred dollars for even the most basic courses.

Rosetta stone pricing page in 2009 [Source]

“The majority of these people [who want to learn another language], like 800 million of them, are learning English, and don’t have very much money…The majority are not learning French because they want to get ready for a trip to Paris over the summer. They’re learning a language to get a job at a call center.” – Luis von Ahn

This estimated audience of 800 million people didn’t have an accessible way to learn a language. By building for an audience that had always been overlooked by the industry, Duolingo was attracting a huge and engaged market.

The size of the market was key to laying the foundation for Duolingo’s success. Duolingo was able to use the scale of their target market to beta test their idea and figure out early on what resonated with users.

But they didn’t just crowdsource feedback. The plan was eventually to crowdsource free labor for another lofty goal: translating the web. von Ahn realized the potential market for translated web content when he saw that his family and friends who couldn’t read English didn’t have access to the same internet content as English speakers. Duolingo’s early monetization plan was to charge businesses for the content that users translated as a byproduct of studying a language. In its first few years, Duolingo didn’t actually partner with companies to build out this B2B service, but they designed their early app with the goal of eventually selling crowdsourced translations.

That’s how the company’s early premise—“learn a new language while translating the web”—was born.

Let’s take a closer look at how Duolingo attracted a huge market early on, and then leveraged their market’s scale to lay the foundations for their business.

2009: Duolingo started out as a project led by Carnegie Mellon computer science professor Luis von Ahn and one of his PhD students, Severin Hacker. von Ahn was looking for a new project after he’d sold his previous company, reCAPTCHA, to Google. This previous company laid the early foundations for crowdsourcing labor in exchange for a different type of value. reCAPTCHA asks users to identify letters and numbers to verify that the user is human, and at the same time, uses free labor to verify words that scanners can’t recognize. von Ahn later used the same idea of leveraging crowdsourced labor to build Duolingo.

von Ahn was looking to flex what he’d learned from this business model in a new and bigger space. At the same time, he started discussing an idea for an educational tool with Hacker, his PhD student. They’d both seen firsthand the importance of good language education. von Ahn grew up in Guatemala, where learning English was incredibly expensive. Meanwhile, Hacker grew up in Switzerland—a country with four national languages. This shared appreciation for language education, as well as the untapped market potential, motivated them to start working on an accessible language learning alternative.

2011: Hacker and von Ahn worked on their idea without announcing it publicly for two years. But behind the scenes, they were already getting investors on board. Before they launched their beta, Duolingo had raised $3.3 million in a Series A led by Union Square Ventures and Ashton Kutcher, the celebrity-turned-tech-investor. According to USV’s investment announcement, Duolingo’s pitch to investors was less about creating a free education tool and more about building a sustainable way to generate human translations of the web on a large scale.

“For Luis’s purposes machine translation is not good enough. Google translate will give you some sense of what is on a page but humans can still do a much better job. The difference is painfully obvious if you want to read a long blog post or an article from a foreign media site. The challenge Luis, Severin Hacker, and the rest of the team at Duolingo have set for themselves is how to get humans to translate the web. Their solution is to make translation the byproduct of something many humans around the globe are already doing: learning a new language.” – Brad Burnham, Partner at USV

To investors, Duolingo presented not just a social opportunity, but the ability to strengthen and widen the online content network. And as a very important byproduct, there was the potential to make a lot of money in the $300 million translation market from companies who needed web content translated.

That same year, von Ahn first introduced the idea of Duolingo to the public in a TED talk he gave about crowdsourcing, which he called massive online collaboration. He introduced the potential of using the online community for free language education. This earliest form of promotion was critical—the TED talk allowed von Ahn to reach a huge early audience with relevant, and not overtly sales-y ideas that primed them to love the Duolingo product. The talk was viewed by over 1 million people, and von Ahn attributes getting over 300,000 users to sign up for Duolingo’s private beta later that year as a result of his TED talk. It was one of only a few forms of early marketing Duolingo engaged in.

Duolingo landing page, July 2011 [Source]

During their beta, over 100,000 people used Duolingo and over 500,000 people were on a waiting list to try it—which speaks to the huge market the company targeted. Of the 100,000 people who used Duolingo, about 30,000 became regular users, visiting the site for at least 30 minutes a week simply because it solved a pain point for them in a way that no other product ever had.

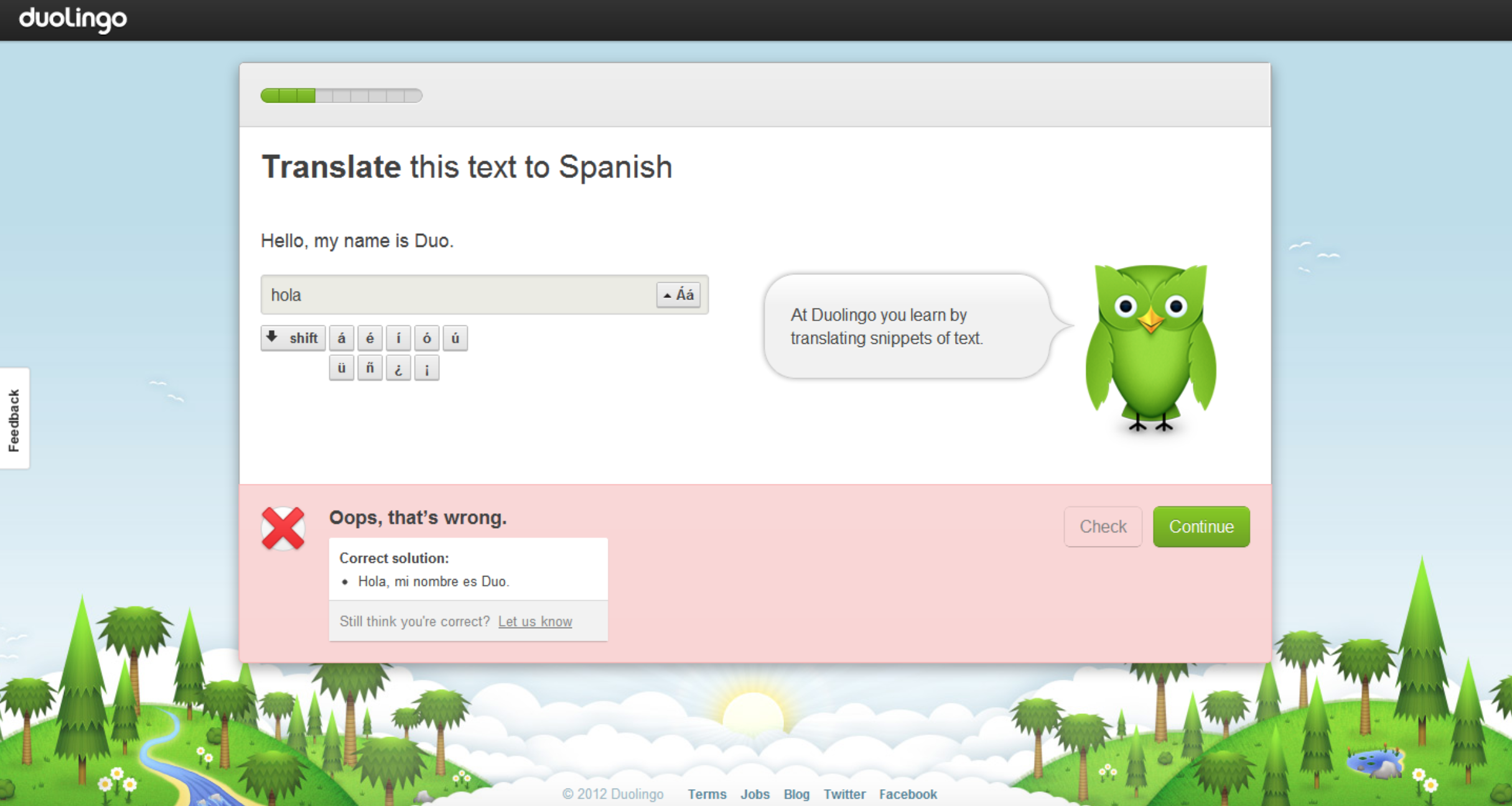

2012: In June of 2012, Duolingo ended their beta and opened their service to everyone. At this time, the product offered lessons in four languages: English, Spanish, French, and German. The product consisted of lessons to learn new vocabulary, and translation exercises to practice grammar and syntax. According to Ahn, early users were motivated to use the app and learn by translating because the product reinforced its own importance. “When you’re doing the real-world stuff, such as reading a news report in German or French, you really feel like you’re accomplishing something,” said von Ahn. “It reinforces why you’re working to understand this new language.”

Duolingo’s benefits lived up to the promise—an independent study released in 2012 found that, on average, 34 hours spent on Duolingo were equivalent to one semester learning a language at a university.

Learning through translating resonated with the end users. They were already generating reliable translations of online texts, even though Duolingo hadn’t started selling these translations to companies yet. Duolingo’s software was set up to produce high-quality translations because it compares the results from multiple students’ translations to settle on a final “correct” translation. According to von Ahn, the results are better than automated translation and just short of professional quality. This made them some of the best and most affordable content translations out there.

Later that year, in September, Duolingo announced their $15 million Series B. This was an important milestone for product development—the company said they planned to use the funding to add more languages and build a mobile app. The product was already improving and evolving—the app constantly learned about users’ abilities as they translated and only showed them exercises that were appropriate for their skill level. The company had already set up systems to track where users came from, how much time they spent in the app, and why they wanted to learn a language.

At this point, Duolingo was growing quickly as a free service and had around 250,000 weekly active users learning languages. They weren’t monetizing yet, but had made more plans to generate revenue by charging users to upload content they wanted other users to translate.

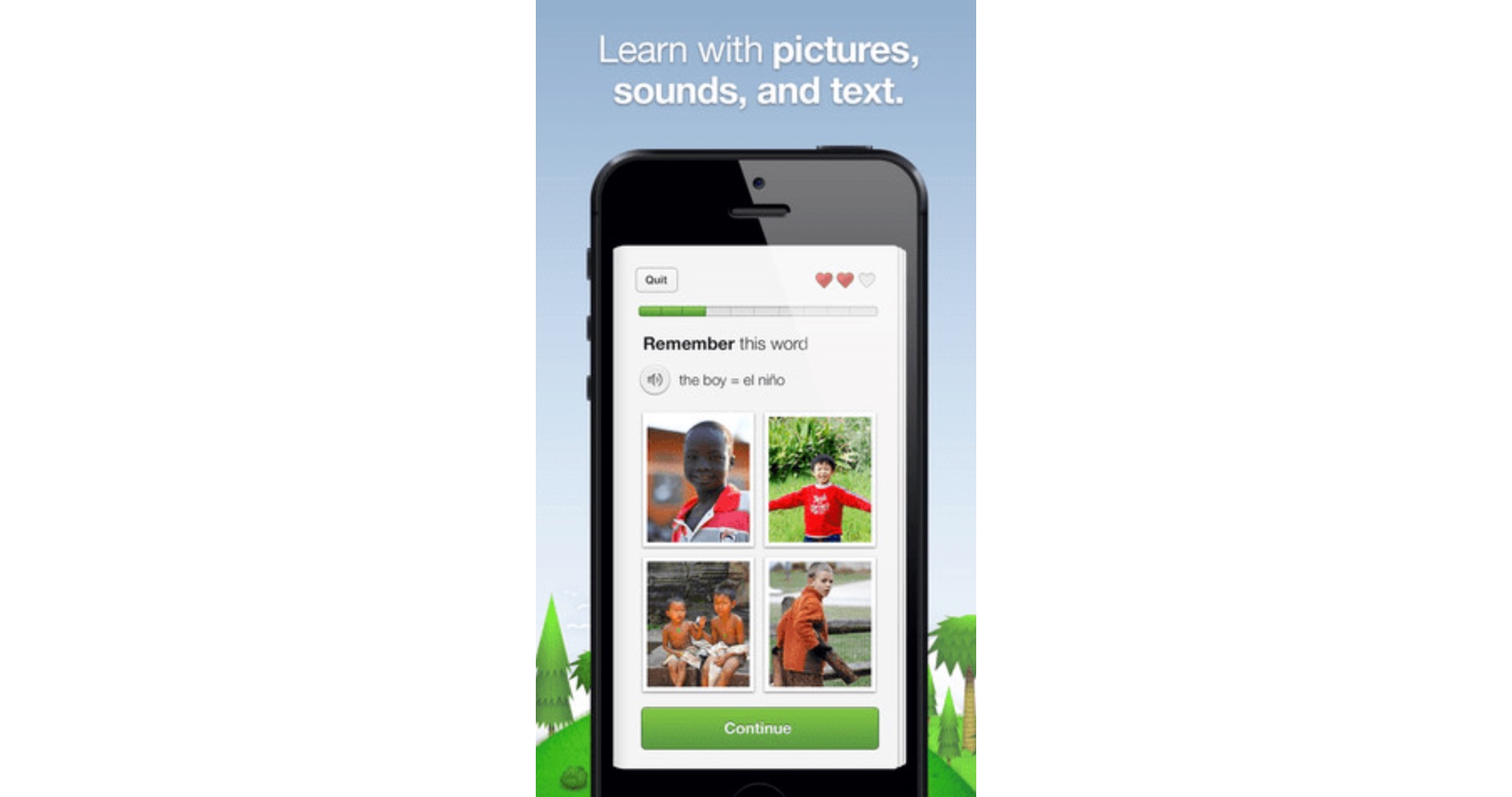

In November 2012, Duolingo launched their iPhone app. This made lessons even more accessible to users on the go and gave Duolingo more options to gamify the user experience—it used pictures, video clips, and the phone’s microphone to help users learn words, write, and speak.

Releasing a mobile app opened up options to grow engagement down the line with phone-specific features like push notifications. Features like these helped make the app even more addictive.

These early successes in growing a user base and releasing web and mobile apps gave Duolingo a strong start. They’d built their product around a creative business model and united two tangentially related, high-demand services—affordable language education and web content translation. The company had built a solid foundation with a strong vision for the future, but they still weren’t generating revenue. The consumer app was their focus, and they hadn’t started building out their B2B service or partnering with companies to sell translations.

But Duolingo had investor expectations to meet. They also had to build a machine that would allow for future growth. Now they had to shift their attention to monetization. Charging users wasn’t an option: keeping the product free and accessible was the central tenet of Duolingo’s mission. Instead, their next step was to double down on the translation services they’d been testing out with their early users and understand the B2B market.

2013 – 2014: New B2B and UGC sources help monetize the business

Duolingo proved they had a good idea. With over $18 million in funding behind them and tens of thousands of new users signing up every day, they could safely say they had a huge potential market and that both users and investors were interested in their unique way of approaching language learning.

But it’s not enough to just have a good idea. You have to make money. They had to find a creative, sustainable way to generate revenue so they could keep growing the business within the parameters they’d set out at the beginning. They’d already built a wildly popular free product, and to start charging users could compromise their user growth. On the other hand, von Ahn didn’t like the idea of selling ads. Duolingo had to focus on keeping users in the app, and ads would definitely detract from the user experience.

Instead of monetizing in these more traditional ways, Duolingo went back to their company’s basic tenets. The company promised that users would “learn a new language while translating the web,” and the translations students generated as a byproduct of their lessons were actually incredibly valuable to the companies who published the original content. As Duolingo’s investors knew, this was a huge potential source of revenue.

So Duolingo began experimenting. Over the next few years, they started partnering with other companies and selling them the translated content that users generated. This subsidized the cost of learning for the users, and helped Duolingo continue providing the app for free.

At the same time, Duolingo made UX experimentation a priority. Now there was money at stake—Duolingo had to keep users engaged in the free app to continue generating these revenue-earning translations. To optimize their app for the user as much as possible, they meticulously tested every aspect of UX, gamified the product, and used their findings to make data-driven decisions.

Here’s a closer look at how Duolingo built out their B2B monetization model, and doubled down on UX testing to ensure a steady stream of revenue-earning user generated translations.

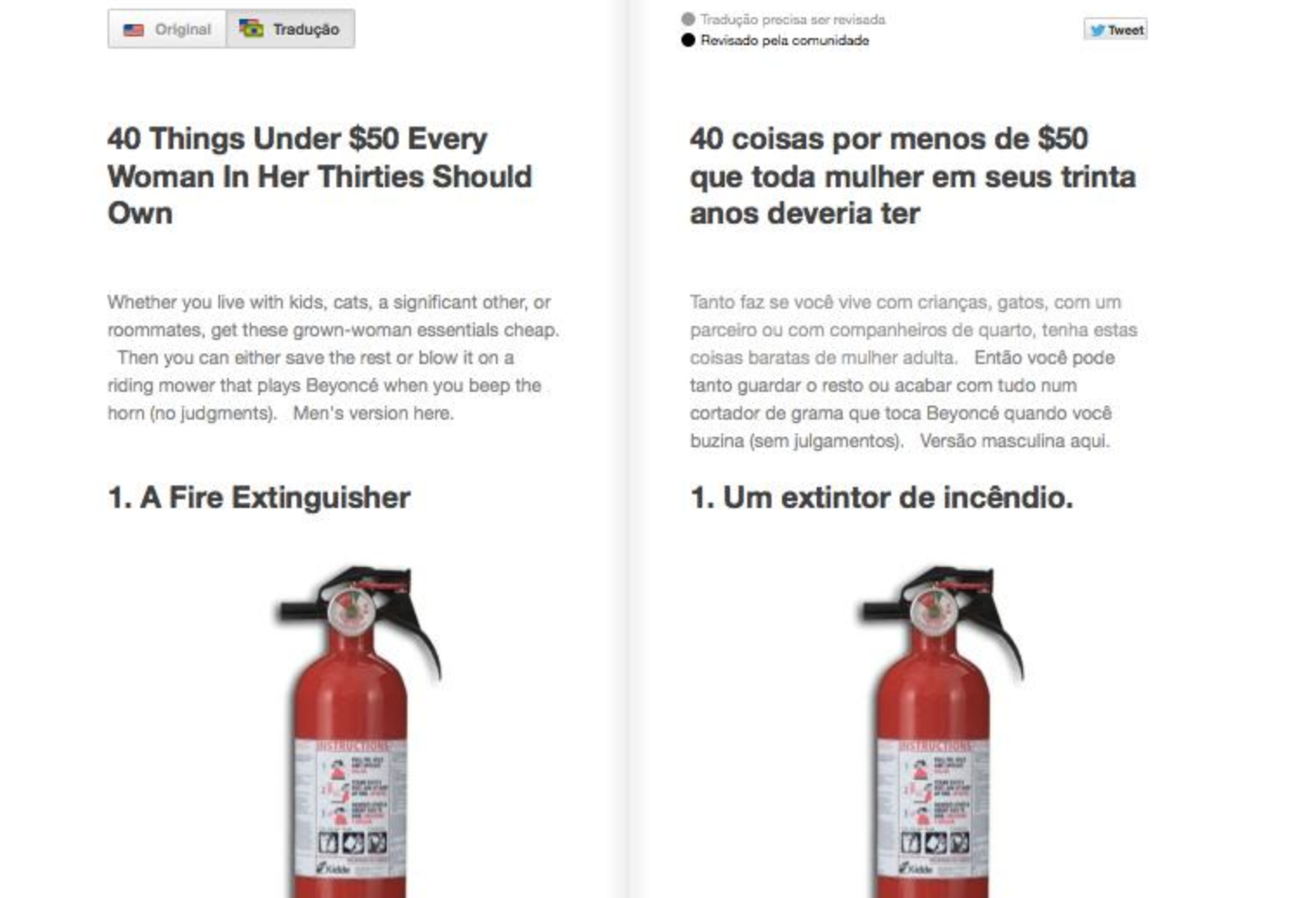

2013: For the first time, Duolingo announced partnerships with BuzzFeed and CNN. This was important for Duolingo because it marked the start of a new B2B monetization model—BuzzFeed and CNN paid Duolingo for users’ translated content. At first, the only B2B translation services offered were for people who were learning English to translate English articles into their own language.

An example of the type of online content that a Duolingo user might translate. [Source]

Around the time Duolingo started selling translations, users translated about 600 articles per day. But only 10% of those translated articles generated revenue for Duolingo. There was still a lot of room for revenue growth.

In 2013, Duolingo was named App of the Year by Apple, reinforcing how popular and useful it was among users. At this point they offered six languages, adding Italian and Portuguese into the mix.

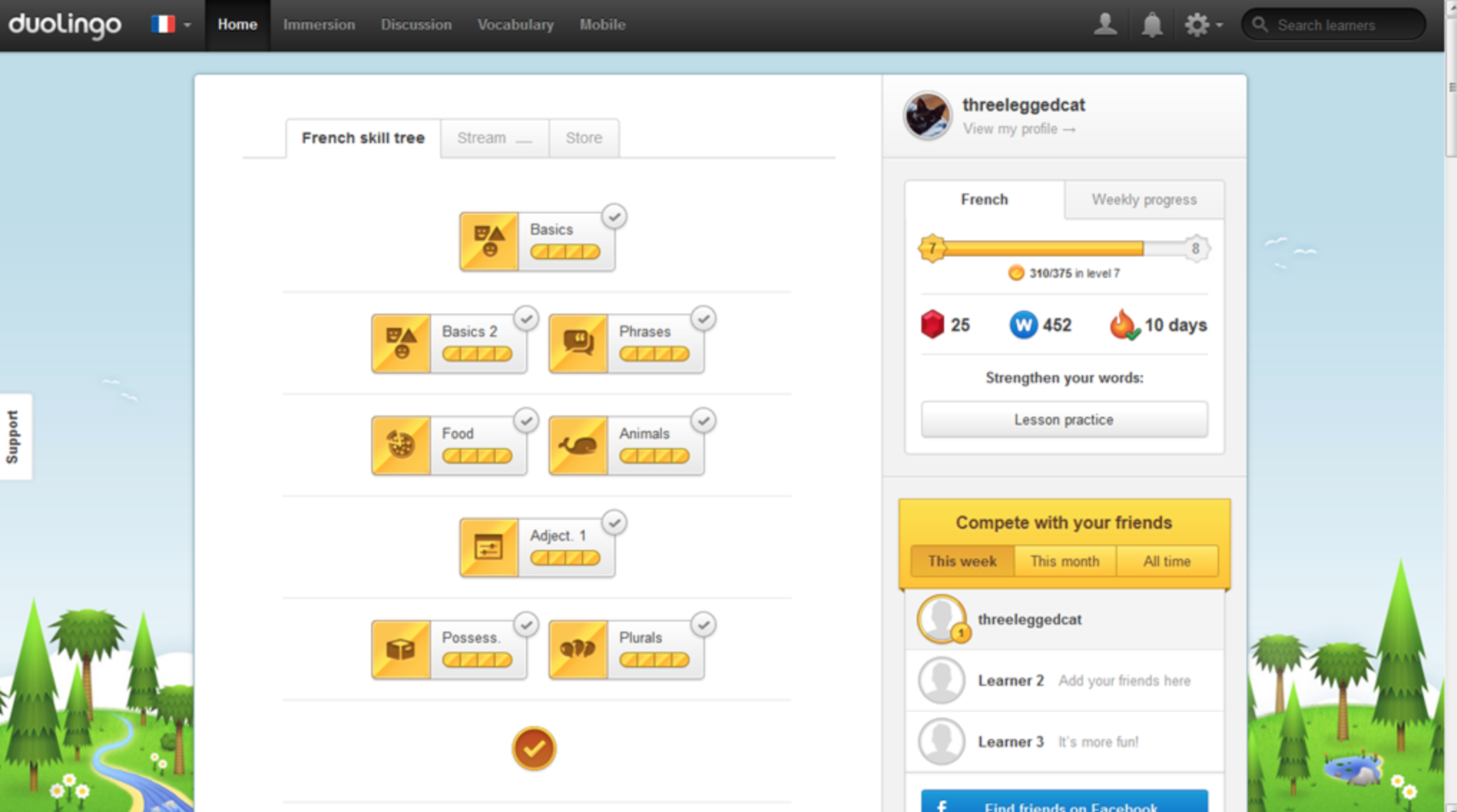

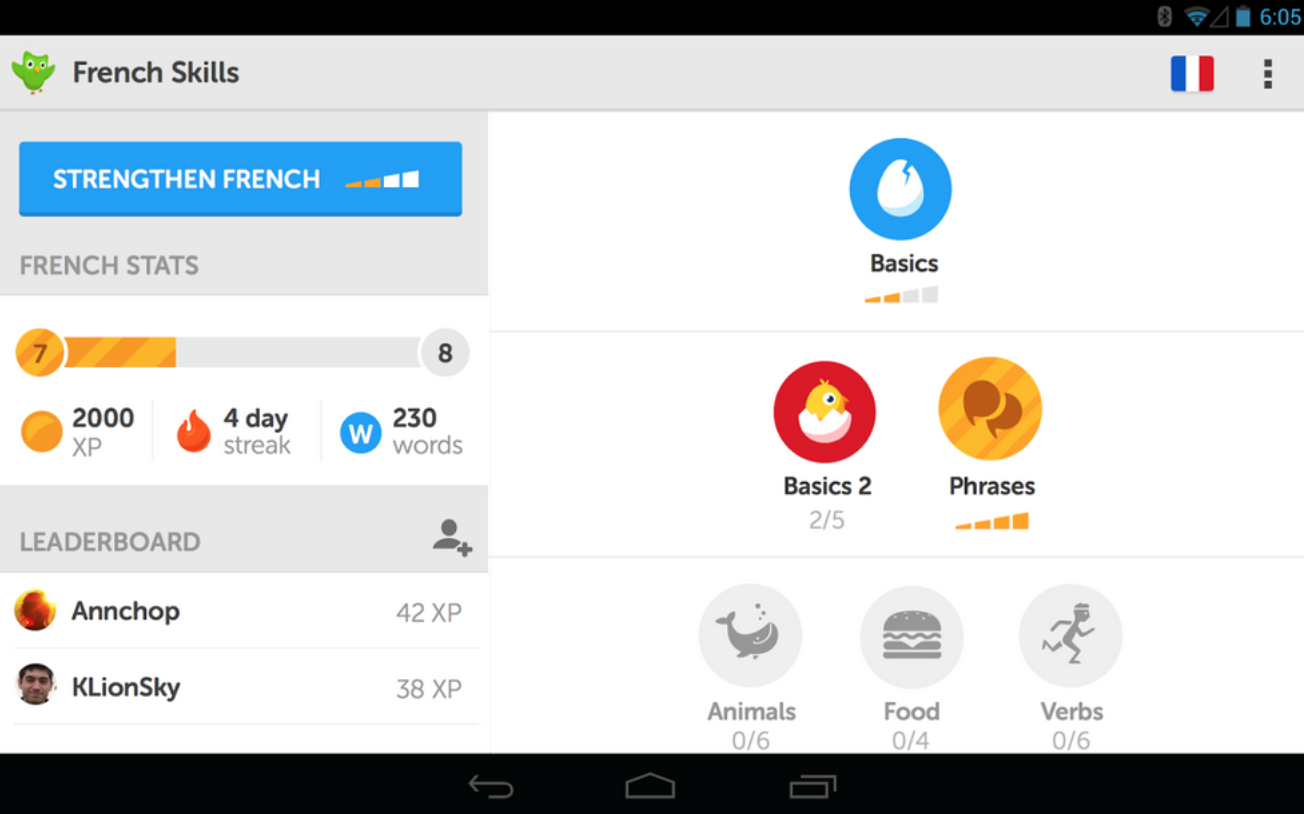

The team worked to constantly gamify the user experience of the app, which was incredibly important for getting people to use Duolingo habitually. Gina Gotthilf, VP of Growth at Duolingo, says that consistent usage is key for users to get the full value of the product: “There’s no way one can learn a language on just Saturdays or Sundays. We need to get people to do it every day or every other day for languages to stick.” Retention is also essential for building a strong and growing user base.

One of their most important gamification features was the addition of streaks, which keep track of how many days a user logs lessons in the app. The growth team A/B tested everything from setting streak goals, the timing of push notifications to keep up streaks, and the copywriting of the reminders. They found that streaks really excited and resonated with users, and each of these tiny optimizations increased DAU by full percentage points.

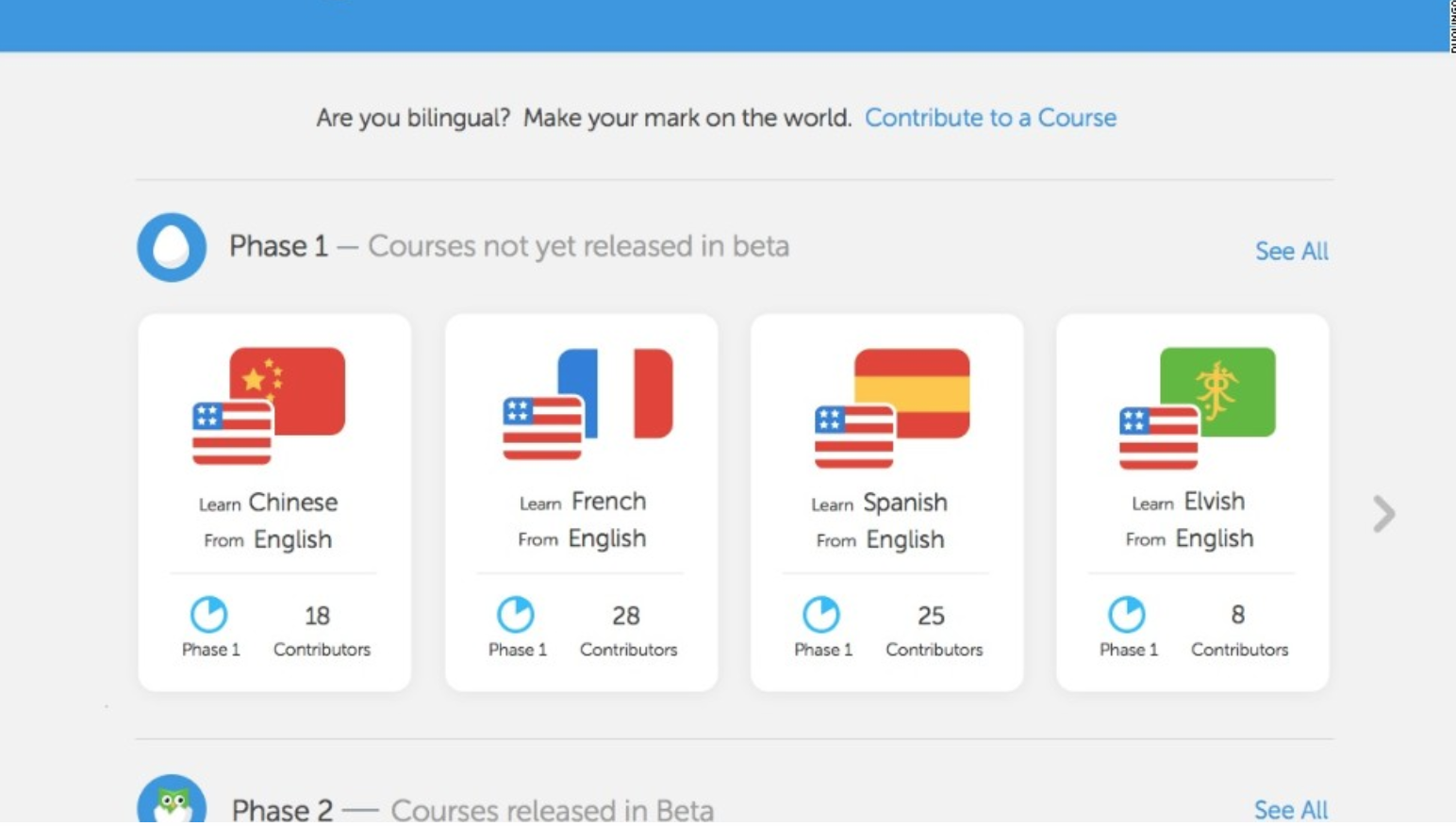

In the same year, Duolingo took another step to increase community engagement and build more value into their product by creating Duolingo Incubator. This is a program that allows contributors to volunteer to create courses for languages that are not yet available on Duolingo—or, in some cases, on any traditional language learning service.

With Duolingo Incubator, the company used its crowdsourcing model in yet another way to grow usage from people who were interested in languages the company hadn’t added yet. Interestingly, these additional courses were created by volunteers who were not compensated at all: von Ahn said, “Our objective is to teach the world languages for free, so we also expect others to collaborate for free.” This was enough incentive for people—von Ahn got thousands of emails from people willing to collaborate, and not long after launching the program, over 20,000 people had applied to create courses.

2014: In February, Duolingo announced their $20 million Series C. At this point, Duolingo had 25 million registered users and around 12.5 million active users. The company reportedly decided to raise money because they’d received inbound interest from investors, especially Kleiner Perkins, who led the round.

Duolingo announced that they planned to use the funding to hire more talent, add new languages, and specifically to add a “groups” feature that would make it easier for classroom teachers and big companies to use Duolingo. Though their B2B service was underway and they were planning to open a self-serve translation portal to grow revenue, von Ahn said that revenue still wasn’t his priority. “Our main goal going forward is to become the de facto way to learn a language.” His idea was that growing the user base would indirectly strengthen the translation—the moneymaking—side of the business.

Growing product usage to strengthen Duolingo’s translation services was critical for the company at this time. It was the backbone of their monetization model, and it fueled their careful and systematic product optimization.

Their A/B testing process created a virtuous cycle. The more the team grew usage by making product optimizations, the more they could test and measure with a bigger sample size. Duolingo’s key tactic for successfully gamifying their product and making it addictive was simply running lots and lots of tests. By using data to understand exactly what their users responded to, they were able to tap into user psychology and create the right rewards and incentives.

These improvements were incremental, like adding a red notification dot to their app’s icon (1.6% increase in DAU), moving the signup screen back a few steps (20% increase in DAUs), and changing the copy of their streak notifications (5% increase in DAUs). But these changes were constant and they added up.

Duolingo UX in 2014 with gamified dashboard. [Source]

The focus on growing usage reflected Duolingo’s general attitude that the end users were their main priority. Even as they tried to monetize by growing a B2B service, the company’s focus was still on the consumers. Soon the company realized that expanding their B2B services was going to require a more enterprise sales-driven model—which meant potentially less attention on the product and the users.

To avoid this, instead of doubling down on their B2B efforts, Duolingo started looking for another sustainable opportunity to monetize.

2014-Present: A new mission—and a new business model to match

Duolingo had the beginnings of a really profitable business model for a B2B translation service—they could afford to charge less than the industry average, they could provide nuanced human translations, and they could finance their free education app.

The B2B service had been an experiment, and a successful one—but Duolingo realized it wasn’t going to help them build the type of company they wanted. Focusing on the B2B service would divert internal company attention and compromise the consumer product that was already wildly successful. Their newest and most exciting ideas—like their Duolingo Incubator and the potential to dive deeper into language education—were focused around their consumer use case, not their business service.

So instead of trying to split their focus between consumers and businesses, education and translation services, Duolingo sharpened their focus on the consumer. Without the B2B service, they had to find new ways to monetize. This eventually led them to options like serving ads and creating an optional paid plan. Even though they previously said they didn’t want to do this, it now seemed like the lesser of two evils because it still allowed them to focus attention on the consumer side.

The common denominator through all of the changes: they were always able to maintain a free service option for the user.

Let’s look closely at how these changes in Duolingo’s mission, use cases, and monetization strategies have played out over the past few years.

Duolingo officially “tabled” their business translation service in 2014. They continued working with CNN, but stopped accepting any new partnerships with businesses looking to buy translations. Even though it was a successful revenue stream, it no longer aligned with the company’s new set of goals around expanding the consumer use case. Continuing to grow the translation service would have required building out a sales team and shifting to a more enterprise, B2B-style company internally, which would have bifurcated the team’s efforts and attention.

Discontinuing the business translating service parlayed well into the release of a new consumer service.

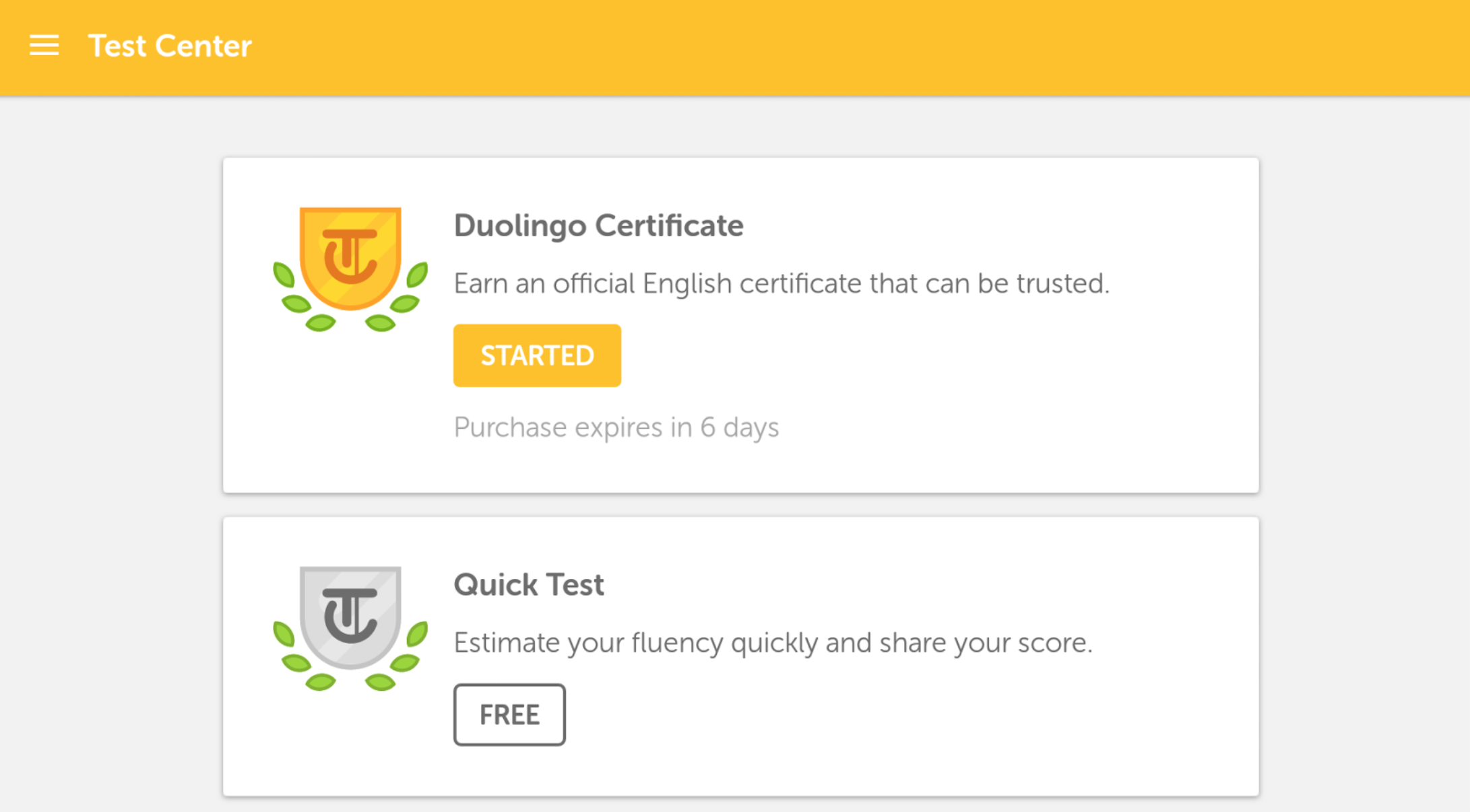

The same year, Duolingo released Test Center, a beta service that allowed users to take a test at home on their own device and receive an English language certification.

An independent study found that scores directly correlate with TOEFL iBT, a standardized English test. This was especially important for the huge market that von Ahn initially had in mind when he designed Duolingo—the 800 million people who wanted to learn English to get a better job. For them, English language certification tests were a barrier because they were very expensive and required travel to the testing center. At $20, Duolingo’s test was much more affordable, and still gave Duolingo a new way to monetize the user base.

It’s certainly challenging to build a new certification that can be viewed as legitimate alongside the industry standards. However, a lot of employers (like Uber), universities (like the Harvard Extension School), and institutions (like the government of Columbia) started recognizing the test as legitimate almost right away. Duolingo helped this along by highlighting studies on its effectiveness and working directly with schools and institutions to get it recognized. This made it a great option for the portion of the market using Duolingo to advance their careers and opportunities.

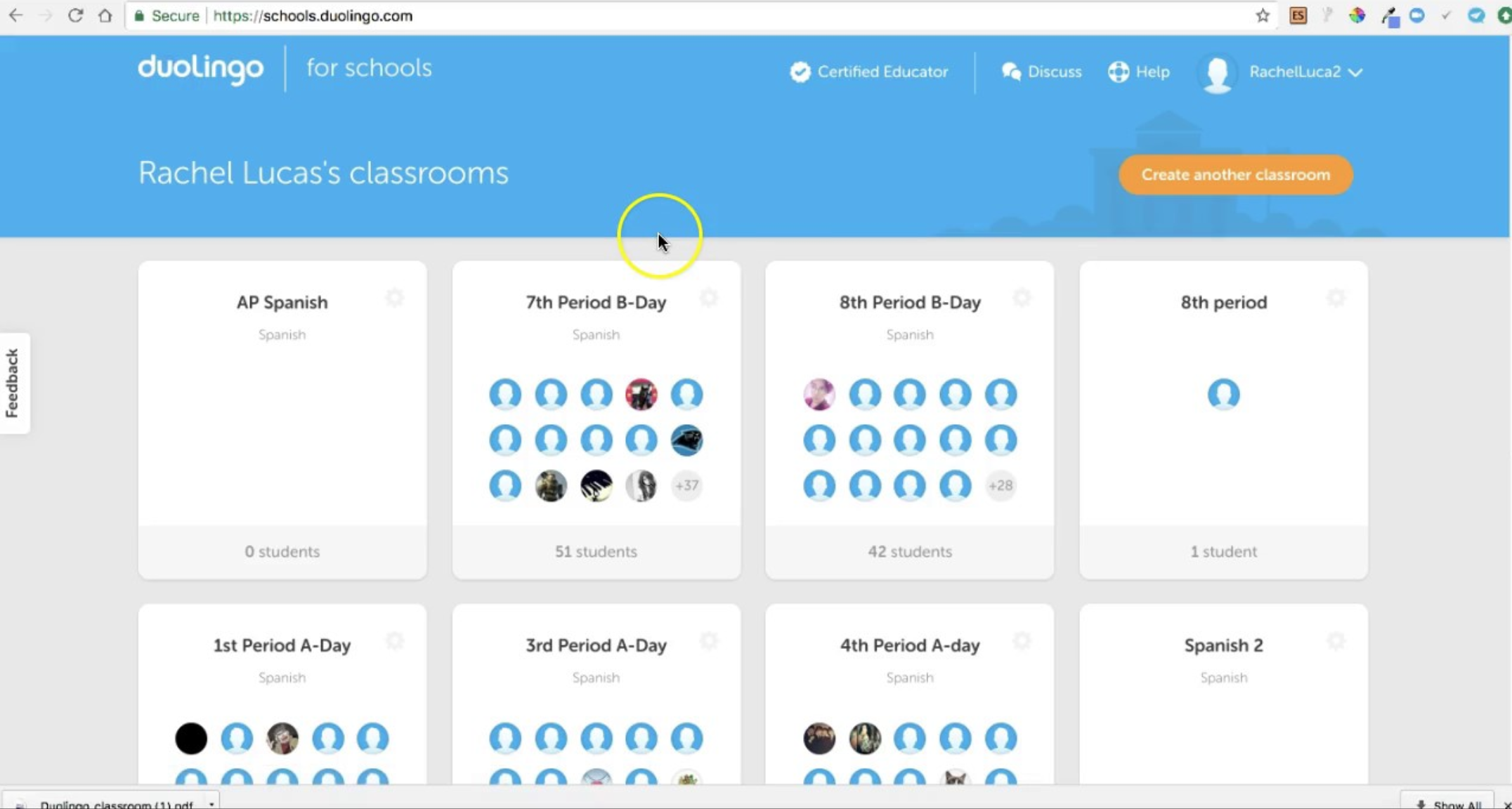

2015: When Duolingo raised their Series C in 2014, one of their goals was to build a feature that would help teachers track students’ progress. The funding they raised provided them with time, capital, and the ability to grow the team from 34 people to around 50—and they were able to dedicate these new resources towards this goal. So in 2015, in response to thousands of requests from teachers and education ministries in governments around the world, the team launched Duolingo for Schools. This is a program that teachers could use in the classroom to teach languages to their students.

The program provided a dashboard for teachers to track students’ progress in Duolingo in a consolidated way. The company planned to continue building out functionality that would help teachers see patterns across incorrect answers, identify the gaps in understanding, and create tailored learning experiences for their students.

Duolingo for Schools was completely free for students and teachers—it wasn’t a revenue stream for the company, but it was essential for increasing usage and making their programming even more accessible and valuable in ways that consumers needed. It grew especially quickly because there was already a huge demand for it from administrators and it was already so popular among students. It also helped a lot that the program was free and accessible in school districts with limited alternatives. In just a few months, 100,000 teachers had already signed up.

With over 100 million worldwide users, Duolingo raised a $45 million Series D. Google Capital led the round and said they were “blown away by Duolingo’s growth and engagement numbers” and cited their potential in the “future of education.” The company planned to use the funding to make their education program even more exciting and adaptive, and to expand further into school systems globally.

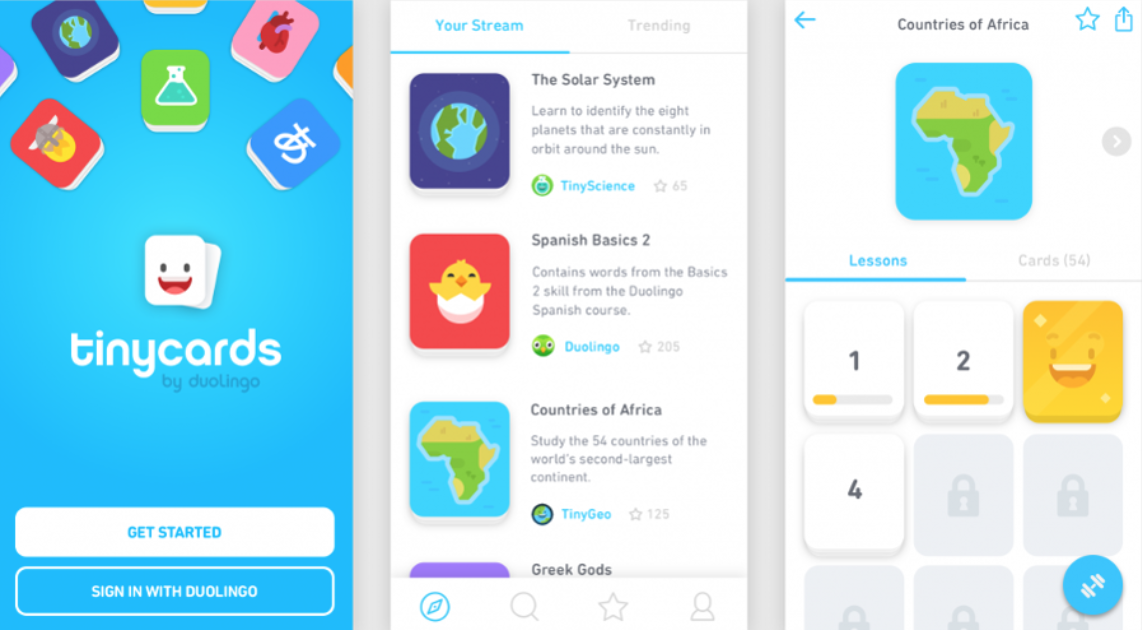

2016: Thanks to their new funding, which brought them up to $83.3 million raised in total, Duolingo was able to start working on solutions for broader opportunities in education technology. Duolingo made the next logical progression to expand their market even further and created their own flashcard app called TinyCards. This helped them gain users in other education verticals besides language. TinyCards was well-positioned to succeed without significant added marketing efforts because there was already a large proven market for offline flashcards, and it was benefitting from Duolingo’s language app distribution channels.

TinyCards had a huge distribution boost from the start because it was tied to Duolingo—it was promoted on all of Duolingo’s sites and users could log in with their Duolingo account. It was free, just like Duolingo, and had many of the same gamified learning principles that made Duolingo so addictive. Within a year, Duolingo reported that users had already created over 200,000 flashcard decks in TinyCards.

2017: Since they stopped growing their business translation service, Duolingo’s main source of revenue was payments for tests in the Test Center. Though they had plenty of funding, they needed to continue building sustainable ways to monetize. This is how Duolingo finally came to the decision to start serving ads to users.

Though they previously said they didn’t want to serve ads, the company saw it as the lesser of two evils—serving ads meant they could monetize without building an enterprise sales team. Maintaining a good experience for the users was still the top priority for Duolingo, so they made sure that the ads were unobtrusive. They only appeared at the end of lessons and didn’t take away from the main objective for users: language learning.

Duolingo also released a subscription Plus plan for Android, Web, and iPhone later in 2017. The paid plan removes ads and lets users download lessons for offline use. The purpose was to continue making Duolingo self-sustainable, while allowing all users the option to continue the service for free.

Duolingo’s most recent fundraising round was a $25 million Series E at a $700 million valuation in July. This most recent valuation is up nearly 50% from their $470 million valuation during their Series D. The company doesn’t release their revenue numbers, but von Ahn says the growing valuation reflects increasing revenue. Duolingo recently reported over 200 million users, 25 million of whom are active monthly. The company says that the next priority on the horizon for them is to grow the company from 80 to 150 people, and specifically hire more engineers and designers.

Duolingo has been increasing investor faith and likely growing revenue. It’s hard to say how much they’re making, and it still seems like they’re figuring out how to be successful with monetization. But, they have more plans for monetization in place than ever before. Monetization is challenging for them because they’re still trying to make money while upholding their core value: providing high-quality language education for users around the world for free.

But going forward, Duolingo has plenty of options. And they’ve gotten to this point—and will likely keep growing—because they’re so committed to testing different business models and being adaptive to what works best for their huge market.

Where Duolingo Can Go From Here

Duolingo has a lot of potential paths as it nails down plans to make money. Here are some ways they can expand their service, grow usage, and add additional revenue streams:

Bifurcate into a consumer-facing app and a B2B translation service: Even though Duolingo didn’t want to do this initially, it is quite common for businesses to grow by targeting consumers and businesses at the same time with multiple products. This strategy could be very successful for Duolingo as long as they continue to allocate resources to the consumer side. With Duolingo’s most recent round of funding and their plans to significantly grow the company, they have the room to build out their B2B side without taking resources, time, or people away from working on their key consumer use cases.

Continue expanding into education: TinyCards was a good first move into the wider education space, but there’s a lot of opportunity for other educational tools with similar monetization models (e.g. ads and optional paid plans). TinyCards lets users study user-generated content around a really wide range of topics from anatomy to geography to Game of Thrones characters. If Duolingo dives deeper into some of these verticals, they can build out entirely new education apps around some of these topics in a similar, gamified way. Some of the best teacher-recommended educational apps right now (according to the TED Ed blog) revolve around poetry, science, and 3D modeling—all potential spaces for Duolingo to grow. This would help them not only expand to language classrooms around the world, but classrooms for many different disciplines.

Branch out into other business segments: Beyond translation, there are other naturally adjacent B2B partnerships that make sense for Duolingo. For example, there are potential partnerships in segments like international travel, where Duolingo could partner with travel agencies or hotels to provide two-week “crash course” lessons for international travelers. As a supplement to their free services, these “crash courses” could be upsells and tap into paid consumer segments. Alternatively, Duolingo could suggest travel options involving their paid partners for users learning particular languages in the app. Duolingo would have to be sure to tie whatever tangential business service they provide closely to their main consumer use case.

Since Duolingo is a private company, it’s difficult to tell exactly what their financials look like—but from their growing usage and growing investor valuation, it seems like they’re set up to expand and continue their success.

3 Key Lessons to Learn from Duolingo

Duolingo did something that no one in the translation and language education space would have ever thought was possible. They created a free language learning app that has tens of millions of users hooked around the world, and grew a successful business along the way.

No matter what space you’re in, Duolingo’s commitment to their vision and the way that they transformed an industry can serve as inspiration. These are the three main takeaways from Duolingo’s journey that can help any business stay adaptable and set themselves up for long-term success.

1. Go after a large market—even larger than your competitors’ markets.

Duolingo could have simply built a gamified Rosetta Stone competitor. It would have been fun and engaging, and they could have sold the end product for hundreds of dollars. After all, Rosetta Stone was a successful company and they were doing well in a decent-sized market.

But instead, Duolingo looked beyond what others were already doing. They considered real problems in language education, and who would be most affected by these problems. This led them to find a group of people who weren’t being served by the options already available—and led them to an even bigger market than their competitors’ market.

It’s easy to look at the current market size of your product or your competitions’ products and take it as a given. But if you can look beyond this, you can find untapped potential that your competitors are completely oblivious to.

So instead of thinking about where your company and your market are right now, work backwards. Set a goal for what you want your company to be doing in 5, 10, or even 20 years, and then think about what that means about the market you’ll have to go after and the type of company you have to build.

For example, if you’re working towards becoming an industry authority on CRMs, you might aim to eventually have 15 million visits a year to your blog. To get there, you’d have to first figure out how to grow your blog from less than 150k yearly visits up to 15 million, and what you’ll have to do at each of those stages along the way (like building an initial blog, finding product-market fit, and developing an efficient content pipeline).

If you’re like Duolingo, going after a huge audience might mean you have to provide something for free. But Duolingo has also demonstrated that there are always creative ways to monetize, and you can make it work if you keep your focus on the end user.

2. A/B test everything, and meticulously track and adjust based on your results.

One of Duolingo’s winning strategies was being data informed. By making micro changes, they were able to grow usage and engagement little by little. These incremental improvements may not have seemed like a lot in the moment—a 1% increase here, a 3% increase there—but over time, it added up. Thanks to their constant tiny optimizations, Duolingo climbed from 100,000 users to 200 million users (a 2000x increase) in 7 years.

For example, one of Duolingo’s most significant optimizations was subtle and even a little counterintuitive. They noticed a lot of users were downloading and even opening the app, but weren’t signing up. To encourage signup, they experimented with moving the singup page back a few screens. They had no idea if it would work, but they hypothesized that by giving users a taste of Duolingo before asking for a signup, they wouldn’t see so many dropoffs here.

They were right. But they never would have known this if they hadn’t A/B tested the placement of the signup screen. With this small adjustment alone, they were able to increase DAUs by 20%.

My best advice for running experiments and making data-driven decisions comes partially from my own experience and partially from Gina Gotthilf at Duolingo:

- Constantly brainstorm ideas for tests. Don’t throw out any ideas until you get to later implementation stages. Then you should evaluate based on how many users it will affect, and prioritize getting statistically significant results for your sample size.

- Use an analytics tool that allows you to tie data and actions to specific users. If you can’t parse through your data with your own tools, it’s worth it to invest in one that gives you high-quality user analytics, like Amplitude.

- Don’t assume that data is only quantitative. Qualitative data can be extremely useful market research, and it helps you get a different understanding of what’s working and what’s not from the user’s perspective.

To set up a successful system for testing and experimentation, you can’t set an endpoint in mind. You have to be open to the idea that one test will lead into another.

3. Don’t be afraid to evolve your business model.

If Duolingo had stuck to their original plan to monetize based on B2B services, they may not have developed all of the interesting and genuinely useful consumer use cases that they have now. Being flexible and experimenting with their business model has allowed them to make important changes that pushed the company forward while staying true to their original mission.

Duolingo had the freedom to change their business model so much because they were in a really big market and they had a lot of data on usage that could back up their hypotheses. They were in an ideal situation to evolve.

But besides Duolingo, there are many household names in SaaS that have changed their business model over time—companies like Dropbox, HubSpot, and New Relic. In fact, for many companies, evolving your business model can be a catalyst for growth because it opens up new markets and opportunities.

My advice for founders who are trying to find the right business model fit for their company is to think about these points:

- What is your product’s value proposition, and what is its time to value?

- What is the competition like in the space?

- What is each of the target customers worth? What is the potential market value?

- What is the quickest way you can help your customers win?

I’m sure in Duolingo’s case, moving away from their B2B translation service was terrifying, especially given their promises to investors. For many companies, making a big business model change is really scary. But if you have a strong vision for your product and a mission to fulfill for your market, sometimes a change in business model is what you need to innovate.

We can expect more surprises from Duolingo

Duolingo has grown so much over the past nine years. They’ve proven how useful they are to hundreds of millions of people around the world while growing their company and figuring out how to build a successful business because they’ve stayed laser focused on the initial goal: helping users learn a new language.

I expect that we’ll see more surprises from Duolingo as they continue to experiment and learn what works best for them and their users.

They have so much potential—and I’m excited to see what’s next.