Exploring the Most Effective Product Workflows in Tech

I recently tweeted:

I see this over and over again. Nailing down an efficient product workflow is one of the biggest pain points companies have.

Startups want to move fast and make things that work. Preparing for scale too early slows you down with too many meetings, tools, and processes that you don’t need. But as you grow your product, team, and business, you have to evolve.

If you think you need to revamp your process for product development, ask one simple question:

What’s the fastest way to get this done?

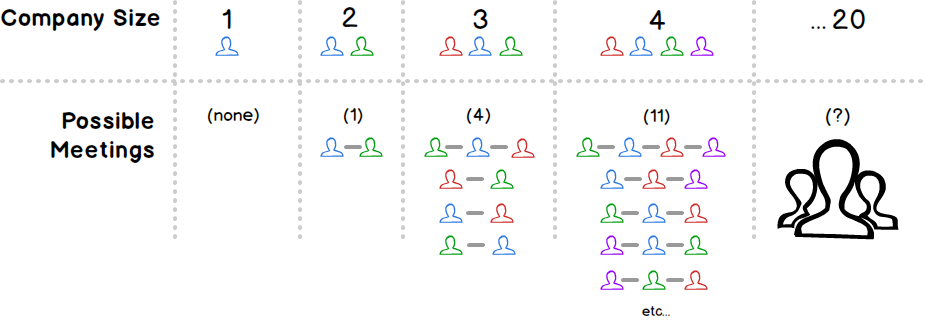

The answer will depend on your customer, your market, and above all, the stage of your company. This great graphic from a product director at Shopify shows how organizational complexity is amplified over time:

In the early stage of your company, you don’t need that many processes because people can simply talk to one another. As a company scales and starts adding multiple teams, you need more formal ways of communicating across teams and to do that you need to start building repeatable processes.

Let’s look at how some of the most effective product teams today structure their workflows. We’ll look at examples from middle and later stage companies to give you ideas for how you can improve.

Middle-Stage Companies: Share Knowledge Between Teams

Early on in a company, you don’t need that many processes because you can just walk over to someone’s desk and talk to them. As a company scales, process becomes really important because you often have to relay information across the office—or even across countries.

When new people join a company, how do they get up to speed on the way things work? Without a reliable system and documentation in place, things start to rapidly fall apart.

The best new team members will have conversations with existing ones to figure out workflow, and they’ll thrive regardless of whether you have processes in place. But you can’t expect to always be hiring people that are good at process—you have to thoughtfully build your own processes from scratch.

How Intercom Ships Quickly

When Eoghan McCabe, Des Traynor, David Barrett and Ciaran Lee started Intercom, they were four friends who worked out of a coffee shop in Dublin. As the product team grew to around 30+ people, they needed a better way to organize their product workflow.

Intercom’s philosophy around building product is to start in small steps and to ship quickly. Paul Adams, VP of Product at Intercom, writes:

“We believe you achieve greatness in 1,000 small steps. Therefore we always optimize for shipping the fastest, smallest, simplest thing that will get us closer to our objective and help us learn what works.”

The product team is organized from top to bottom around achieving this goal. Each product team consists of a Product Manager, Product Designer, Engineering Lead, and 2-4 Product Engineers. Product teams all work together in the same room.

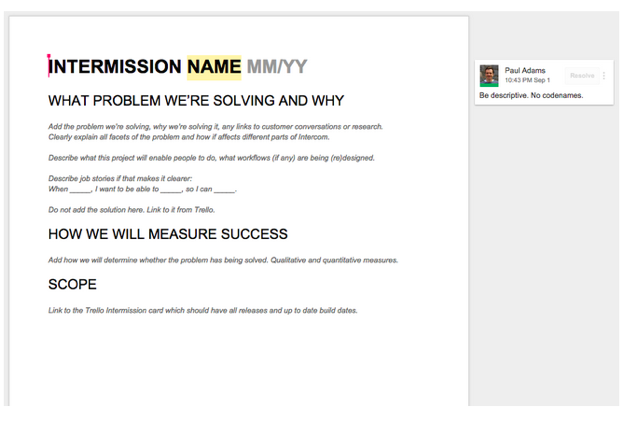

Every project initiative starts with a one-page written document, called an Intermission. It contains three simple things: the problem that’s being solved, how success is measured, and what the scope of the project is. The Intermission is owned by the Product Manager.

The Intermission template

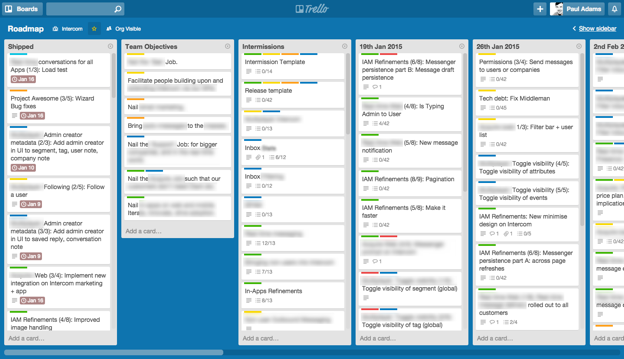

The Intermission document makes sure that everyone on a team knows what they’re building, and why. Once the Intermission moves into play, it’s put on Intercom’s shared roadmap in Trello:

The roadmap contains:

- Intermission card: includes intermission doc, releases within the project, and checklist

- Release card: Contains design work, supporting documentation around product decisions, and a checklist for release (Design, Build, QA, Beta, Full release, Post release)

Each release is tied to a specific Intermission, and owned by a single team. Since Intercom works on 4-6 Intermissions at a time, and 10+ releases at a time, this helps make sure nothing falls through the cracks and that each team is held accountable for a specific release.

Later-Stage Companies: Develop Institutional Knowledge

As companies grow even larger, they start to develop dependencies between product teams. You might have a dev ops team responsible for patching up infrastructure and the backend, another team responsible for the iOS app, and another team for a specific feature in the web app.

The main challenge when you hit this scale is how to keep moving fast, while spreading institutional knowledge. Larger companies have to constantly figure out how to reprioritize goals, reorganize teams, and build better infrastructure.

How Spotify Manages Organizational Complexity

With over 100 million active users, the problems that Spotify has to deal with today are much larger then the ones they grappled with starting out. Things came to a head in 2011, when a single operations team found themselves trying to scale infrastructure for over 10 million users across 1,300 servers.

A startup’s big advantage is the ability to move fast. That’s a luxury that fades away as your product grows in complexity and you add more people to your team. Spotify was no different—its main product challenge was to structure teams to enable a “startup” mentality within a much bigger business.

Spotify attacked this problem in three main ways:

1. Creating Autonomous Units

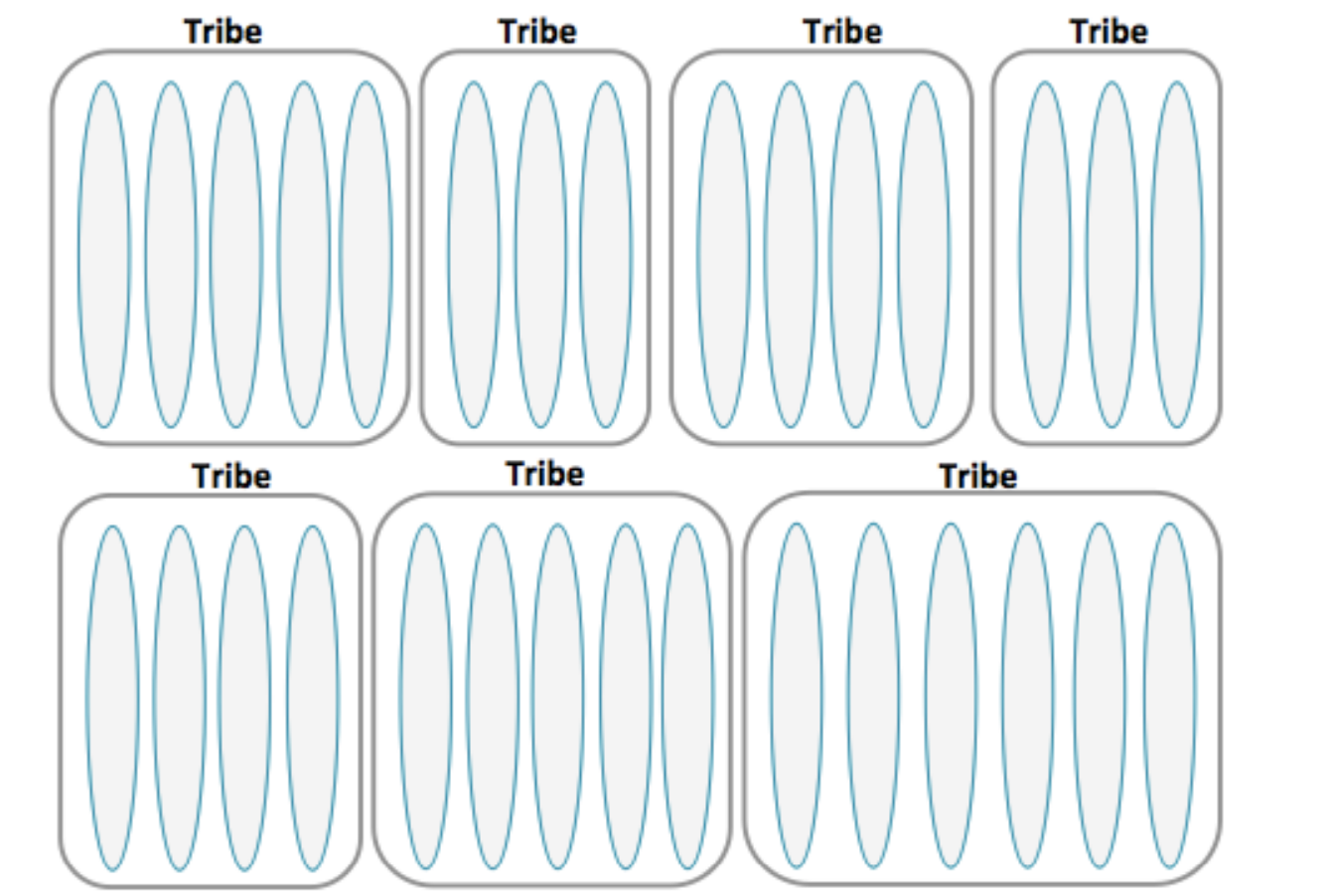

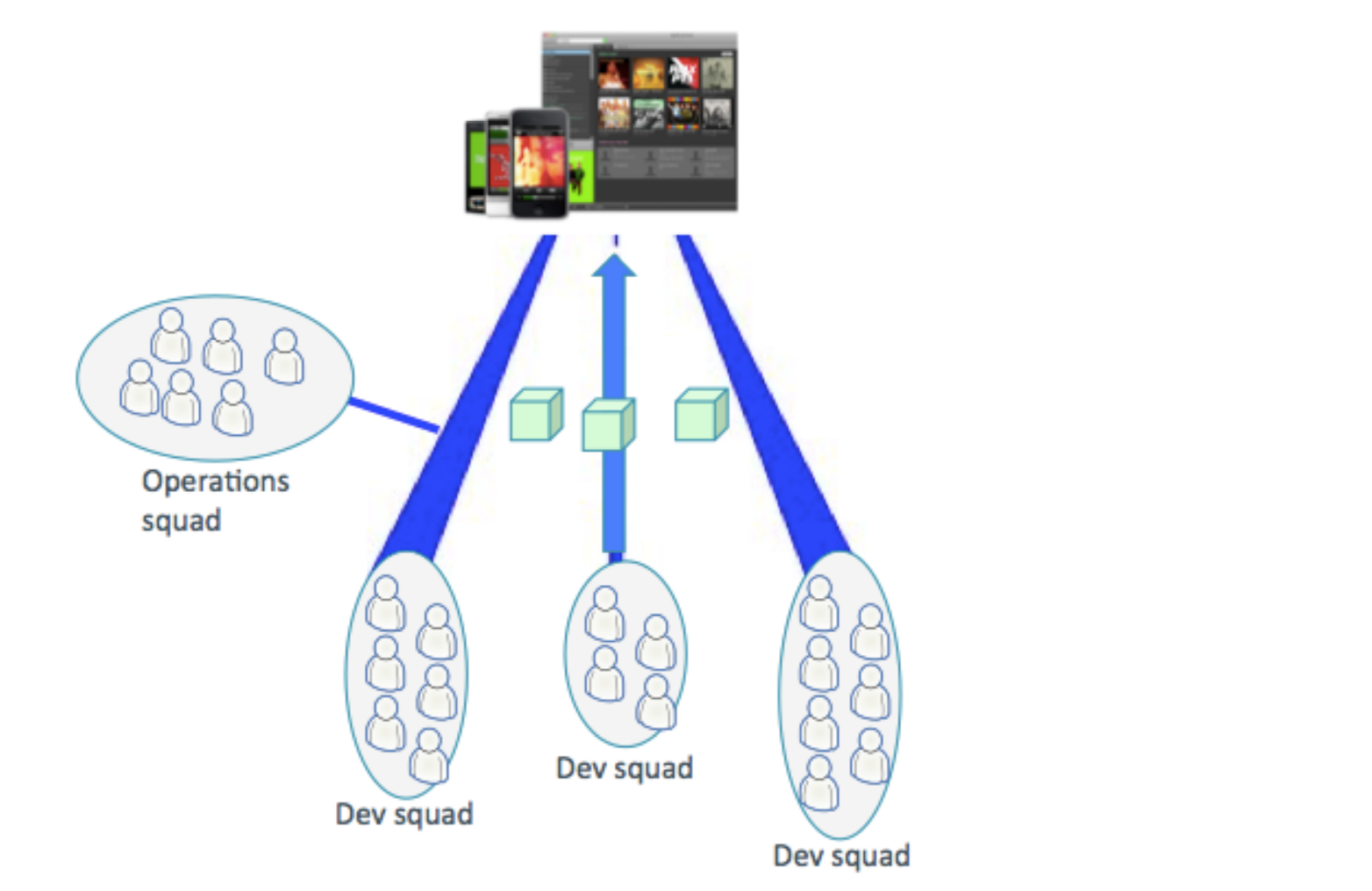

Spotify started by re-engineering product teams into “squads” and “tribes”:

- Squad: The basic team unit, typically eight team members or fewer. A product owner on each team is responsible for prioritizing work done by the team. Squads own specific areas of the application, and are responsible for developing and releasing features end-to-end.

- Tribe: Groups of squads fewer than 100 people each. Tribes are a collection of squads that work in related areas (e.g. music player, backend infrastructure).

Because squads are accountable for the end-to-end production and delivery of new features, from ideation to shipping to A/B testing, they’re able to ship quickly and at a consistent pace.

Product owners within a squad collaborate across tribes to align what squads are working on with the larger mission of the tribe.

2. Eliminating Dependencies

When you have a bunch of autonomous teams working together, you inevitably build up dependencies between teams. Maybe the squad responsible for the music player wants to make it load faster, and they need help on the operations side to do so.

Instead of having a dedicated ops team fix the infrastructure directly, the operations team’s objective is to provide the tools and code that will help the squad figure it out on their own. The main idea is that the next time the squad encounters the same problem, they’ll be able to fix it independently.

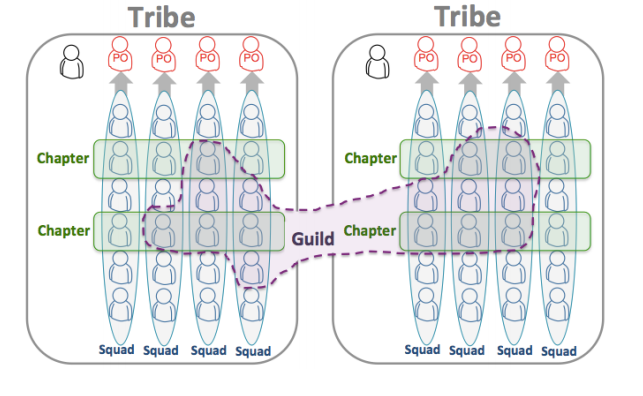

3. Chapters and Guilds

Because squads are autonomous, you inevitably build up redundancy across teams. One squad in one tribe might struggle with and solve the same problem that another squad encountered a year ago. To benefit from shared knowledge across product teams, Spotify structures its teams horizontally as well as vertically.

These are called chapters and guilds:

- Chapter: Groups of team members with similar skills that meet regularly to share expertise. A chapter might be a group of front-end developers, or sysadmins. Chapters are a way of figuring out how to solve problems that require specific expertise across a tribe.

- Guild: Guilds are collections of chapters across the organization. For example, there’s a testing guild that includes all QA testers. Guilds are about sharing knowledge, tools, and code across the company.

When a front-end developer discovers a cool new way to use AngularJS, for example, she documents it and takes it back to her chapter to share. This structure helps promote shared knowledge across teams.

Remember Brook’s Law

Fred Brooks wrote a book in 1975 called the Mythical Man Month. In it, he puts forward the idea that “adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.” This is commonly known as Brook’s Law, and it holds as true today as it did 30+ years ago.

Another way of thinking about Brook’s Law is through this simple Dilbert cartoon:

There’s nothing more exciting than building a product that gets a lot of traction early on. To fan that growth, you rent out a bigger office and hire a bigger team. That’s the fun part. The challenging part is figuring out how to weld these parts together into a well-oiled machine. A lot of times, that means slowing down to move faster.

If you think your product workflow might be broken, ask yourself these questions:

- How long does it take you to deploy? If you have to write a 10-page treatise for a feature that takes two days to code, there’s a problem.

- Do you have too many meetings? You can tell the efficiency of a company simply based on the number of meetings they hold. Six-hour meetings are never productive, and they prevent people from actually making stuff.

- Are you using too many tools? Using too many tools too early in a company is a big problem. If a tool requires training, you might not want to choose it too early in your company.

The way you choose to build and scale a product is a constant process of re-engineering your organization. The best companies—the ones that are built to last—never stop.