How Medium Transformed Online Publishing by Making Long-Form Content Cool Again

Every entrepreneur has to be tenacious, relentless, and focused if they hope to grow their business. Often, however, the most driven founders are those who are focused not only on short-term financial success, but a long-term mission. Jeff Bezos didn’t want Amazon to be the biggest online bookseller on the web. He wanted Amazon to be the biggest retailer in the world, period. Elon Musk wasn’t content to co-found PayPal and make online transactions easier. He also wanted to revolutionize automotive manufacturing in the U.S. and commercialize space travel.

Evan Williams didn’t just want to make blogging easier. He has spent the last twenty years trying to fundamentally change how we publish content online.

Williams’ most recent venture, blogging platform Medium, is the latest attempt in his mission to make online publishing simpler, easier, and more rewarding for writers and readers. Since its inception in 2012, Medium has changed the way many outlets publish online, from major national publications to scrappy upstart blogs. Medium is a relentlessly product-focused company driven by Williams’ mission, but the company has struggled to find a working business model that aligns with that vision. Consumers have long been accustomed to paying for media such as books and music, even after the shift from physical media to digital products. Monetizing online content such as blog posts, on the other hand, has proven extraordinarily difficult for the entire publishing industry, not just Medium—a fact that highlights the enormity and ambition of Williams’ vision.

In this post, we’ll be examining the impact that Medium has had on the blogosphere and the wider world of online publishing. Here are some of the topics we’ll be exploring in this article:

- How Medium’s focus on design and presentation helped popularize long-form writing

- Why Medium has consistently struggled to move beyond traditional online publishing business models

- How Medium’s old-school attempts to monetize contrast starkly with its genuine innovation as a product

By the time Williams co-founded Medium in 2012, he had already spent more than a decade trying to reinvent online publishing—a journey that began with an online publishing platform called Blogger way back in 1999. However, as Williams would later discover, many of the most urgent problems facing the world of online publishing would be just as urgent in 2018 as they were twenty years earlier.

2012-2013: Creating a ‘Place for Ideas’

Evan “Ev” Williams didn’t set out to reinvent online publishing. At least, not right away.

When Williams announced the launch of blogging platform Medium in 2012, he had been working to solve fundamental problems with online publishing for almost twenty years. Williams had launched Blogger with fellow entrepreneur Meg Hourihan way back in 1999, and sold the platform to Google in 2003 for an undisclosed sum. Three years later, in 2006, Williams co-founded microblogging platform Twitter with Jack Dorsey, Noah Glass, and Biz Stone. It wasn’t until 2012, however, that Williams once again turned his attention to what he perceived as serious problems with online publishing as an industry.

By his own admission, Williams freely acknowledged that while Twitter (and, to a lesser extent, Blogger) had created value by empowering ordinary people to create and publish content online, it had also deluged the internet with vast volumes of low-quality content. The democratization of online publishing had been hugely important to the changing landscape of digital media, which had seen a fundamental shift away from established, legacy publications and media outlets toward smaller, indie publishers and individual writers and bloggers. However, democratizing access to online publishing also had an unintended, but entirely predictable effect—it had contributed to an overall decline in the quality of the content being published.

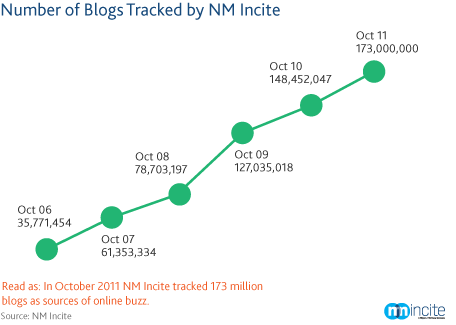

By the end of 2011, there were more than 180M blogs online, an increase of more than 133% from just five years earlier. With so many people publishing content worldwide, it was inevitable that most of it would be useless, poorly written crap. Worse, the immense volume of poor-quality content being published every single day made it that much harder to find publications and writers who were actually worth reading.

Put another way, there was far too much noise and not nearly enough signal.

Williams had already helped popularize blogging with Blogger in the ’90s and reshaped social publishing with Twitter in 2006. With Medium, he had set his sights on creating a place where serious readers could read compelling, useful, engaging written content.

Quality wasn’t Williams’ only concern. He also felt that the prevailing metrics of that time—namely pageviews and unique visitors—were poor indicators of engagement for readers and publishers. These metrics were useful as general insights into a site’s popularity, but did nothing to quantify how readers were actually engaging with the content, or the quality and value of the content itself. Williams wanted to create what he described as a place for “ideas.”

“What kind of ideas? Many kinds: A particular viewpoint on the happenings of the day (or of the past), hard-earned knowledge about how to do something better, a story that makes people laugh, smile, or feel something meaningful. If you have thoughts to share that you want to impact or influence people with—beyond just your friends and beyond 140 characters—we want to provide the tools and the place.” — Evan Williams, founder, Medium

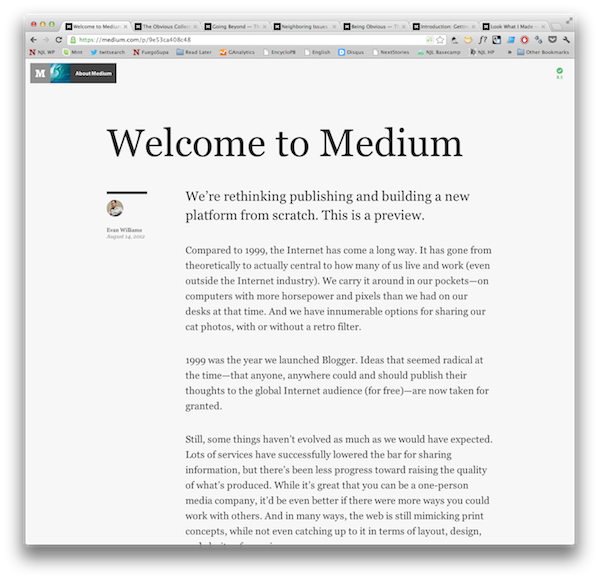

Medium officially launched in 2012 in a closed beta. In a Medium post outlining the announcement, Williams wrote that the closed-beta launch was intentional, as the product’s design and code were still being finalized. The design of Medium, in particular, would be fundamental to the platform’s popularity and success. When Medium launched, online publishing still heavily favored short-form content. Marketers were still trying to figure out how to bridge the “attention gap,” and audiences were already beginning to experience information fatigue.

Medium wanted to change all that.

Despite the challenges of publishing long-form content in an age of dwindling attention spans and “snackable content,” Williams felt strongly that thought-provoking, long-form content offered publishers an unparalleled opportunity to drive genuine, meaningful engagement with content in a way that forgettable short-form content could not.

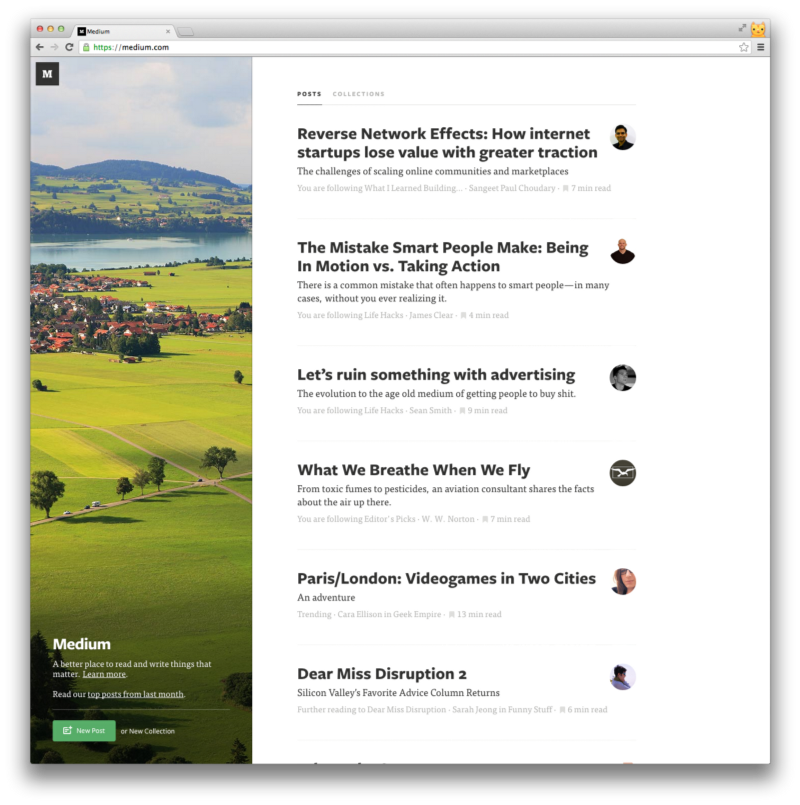

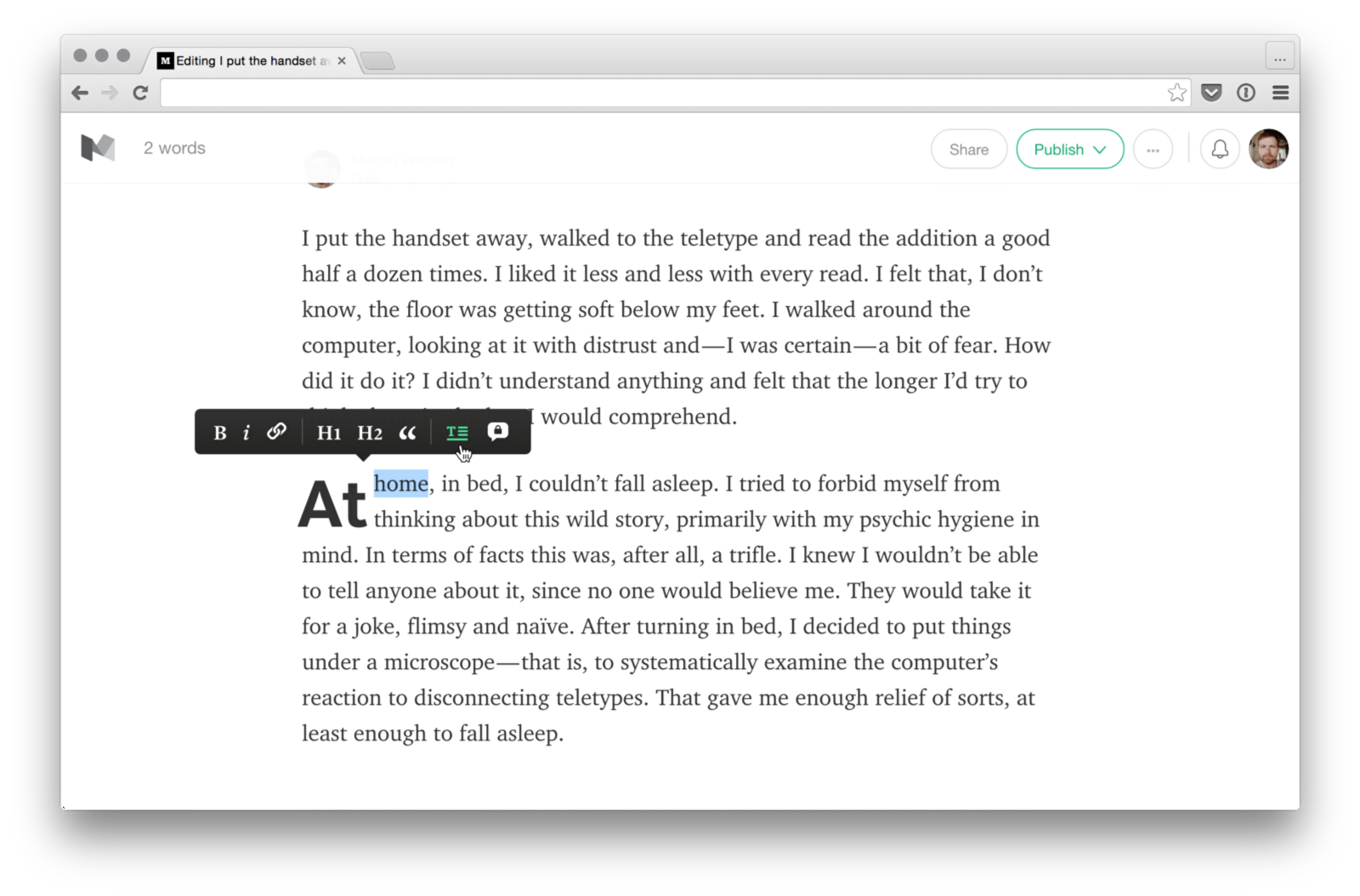

From the outset, Medium intentionally positioned itself as a new way to publish content online. Its interface was beautifully minimal. Content was organized into “collections” around certain themes, and presented in a tiled format. Medium’s sleek interface didn’t just look gorgeous for readers; it was just as streamlined and elegant to use as a writer or publisher. Medium did away with the cluttered toolbars favored by other blogging tools in favor of a simple, markdown-based interface. This wasn’t just smart from an engagement perspective. It also broke down many of the barriers between the writer and the reader. This immediacy looked—and felt—completely different to anything else on the web. In this regard, Medium was hugely influential in making content online legible and easier to read, particularly the long-form content the platform would come to be known for.

Medium’s sophisticated, magazine editorial-style aesthetic distinguished the platform very early on. Tech press and media critics alike praised the new site for its bold design choices and the eclectic variety of content being published on the site. Many respected and notable journalists including Quinn Norton, Joshua Davis, and Michele Catalano began publishing long-form content on Medium, which gave the platform additional credibility. Medium built upon this momentum by hiring experienced journalists and editors, including former Wired editor Evan Hansen, to oversee the platform’s editorial operations.

Beyond the considerable influence that Medium exerted over broader web design trends in general, the site also practically single-handedly reinvigorated interest in long-form content online. Prior to Medium’s launch, many sites shied away from publishing longer articles. Conventional wisdom of the time stated that readers not only didn’t want to read longer articles, their dwindling attention spans made it practically impossible. Medium challenged this idea—and was ultimately vindicated.

“It’s also clear that the way media is changing isn’t entirely positive when it comes to creating a more informed citizenry. Now that we’ve made sharing information virtually effortless, how do we increase depth of understanding, while also creating a level playing field that encourages ideas that come from anywhere?” — Evan Williams, founder, Medium

For all intents and purposes, Medium’s launch went extraordinarily well. The site looked and felt great for readers and publishers. The platform’s readership was growing quickly, thanks in large part to the site’s beautifully minimal interface. Established journalists, writers, and thinkers were migrating to the site from other publications and even personal websites.

From a product perspective, Medium approached categorization in an unconventional way. Rather than adding categories to posts, Medium writers add posts to categories. To Williams, this principle was an extension of his vision of truly democratizing online publishing; quality content should rise to the top, regardless of who wrote it. On the surface, this is a noble ideal and one that aligns strongly with Williams’ original vision for Medium.

However, as many writers soon figured out, it was far less egalitarian than it seemed and created unique problems of trust among the platform’s slowly growing roster of writers. Unlike virtually every other blog, Medium did not redirect users to an author page when they clicked on a writer’s byline in a Medium article. Instead, they were taken to that writer’s Twitter profile. Williams claimed he wanted to build a “place for ideas” where quality reigned supreme and content spoke for itself—but what about when Medium inevitably attempted to monetize its growing repository of quality content? Would writers be able to assert authorial rights over their work, or were they sacrificing ownership for exposure? Many writers were keen to publish their work on Medium, but just as many were deeply skeptical of the promises made by yet another media start-up to “revolutionize” online publishing. The fact that Medium did not yet have a clear business model only served to heighten this skepticism.

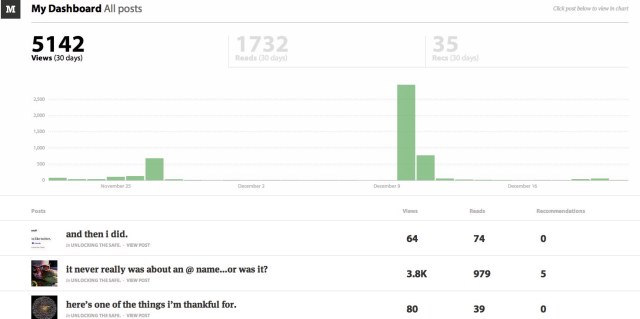

Rudimentary analytics functionality was added to Medium in December 2012. Branded as Stats and Reader Interaction, the feature promised publishers greater insights into how their content was performing on the platform. This was also another great example of how Medium wanted to fundamentally change online content. It wanted to connect web analytics at the back end to notes and reader annotations on the front end to give audiences a new way to interact with online content and publishers new ways to quantify and measure that engagement.

“The goal of Medium is to enable and support quality, rather than just popularity, so our philosophy around stats is that we need to provide meaningful metrics. Medium stats provide feedback that normal web analytics don’t give you.”

Initially, the “meaningful metrics” Medium offered users were limited to just three elements: Views, Reads, and Recommendations. Interestingly, Medium chose to differentiate between pageviews and Reads from the very beginning. Views were counted as typical pageviews are in any analytics system. Reads, on the other hand, was a metric much closer in function to scroll depth, and indicated how many people who viewed an article actually read it. This was a genuinely useful metric for writers, as it allowed them to go beyond mere pageviews to see which of their articles were engaging readers most effectively. Eventually, many publications and marketers would move away from relying solely on pageviews and embraced “attention metrics” like Reads enthusiastically—another way in which Medium had a considerable impact on online publishing in general.

In April 2013, Medium made its first acquisition before it had even exited its closed beta period when it bought online science and technology publication, Matter. Co-founded by former Guardian technology journalist Bobbie Johnson, Matter was highly regarded for the quality of its journalism and the breadth and depth of the topics it featured. Matter recognized the value of—and demand for—long-form journalism, publishing articles more than 5,000 words long for a very modest monthly subscription fee of just 99 cents.

Shortly after acquiring Matter, Medium introduced the first of its collaborative features, annotations. Writers now had the opportunity to invite colleagues to collaborate on shared documents. Upon publication, collaborators were given mentions beneath the finished article. The addition of Medium’s notes and annotations also brought with it another staple of the Medium experience, highlights, a feature that would prove to be one of Medium’s most popular social functions.

Medium continued to tweak its features and experience throughout 2013. In September, Medium began allowing users to follow certain Collections. This allowed readers to curate a more personalized homepage of content when they browsed Medium. The platform also introduced Trending and Latest sections to the Medium homepage to highlight the most popular articles being read across the platform.

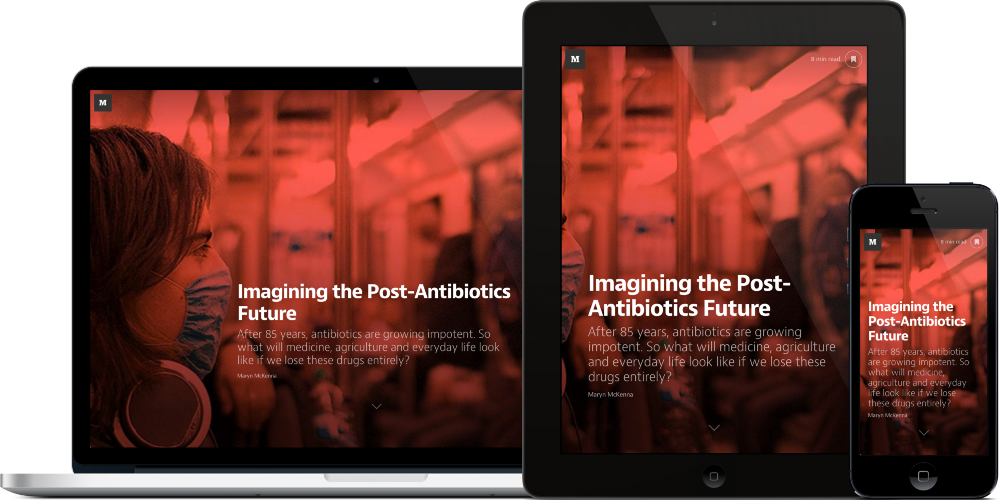

Williams and his team had worked hard to refine and improve the early Medium experience throughout 2013. The platform’s biggest update of the year came in December 2013 with the official launch of “Medium 1.0.” Medium was finally ready to exit its closed beta. The biggest visual change to Medium 1.0 was the launch of Stories, rich, visually immersive magazine-style articles with beautiful typography, layout, and imagery that looked amazing on any device.

Medium also made sweeping changes to how Collections were curated and moderated, which gave “editors”—Medium’s term for the original creators of Collections—sole editorial authority over which posts were published. Although some writers complained about the perceived gatekeeping that editors could exercise over which writers were published, it was a generally solid move toward more proactive curation in an attempt to maintain the high quality Medium had built itself upon.

A few weeks after the launch of Medium 1.0, the company raised $25M as part of its Series A round of funding in January 2014. The round, which was led by Greylock Partners, alleviated the financial pressure Williams had been under since Medium had launched; Williams had been largely funding site operations using his own funds for months to keep the site going until such point that he felt comfortable approaching external investors.

“Media is still in the midst of a massive shift from print to digital […] Content has increased exponentially, but there is still a lot to be done to help people express their ideas and reach the people who would be most interested. It’s also been a challenge for readers to search for and discover things worth reading.” — Josh Elman, Partner, Greylock Partners

In 2012, Medium was a breath of fresh air in an industry that was stagnating and struggling to find a business model that could succeed where print publications had failed. However, Williams’ lofty ambitions to democratize publishing on the internet and relentless focus on the design and experience of using the platform had taken precedence over a critical element of Medium’s business that Williams had seemingly given little thought—monetization.

2014-2016: Designing the Future of Online Publishing

Between 2014 and 2016, Medium focused almost exclusively on product development. This period saw the platform make sweeping changes to virtually every aspect of the site, including new publishing tools, social functions, and a complete visual rebrand. Medium also grew considerably during this period, accepting more than $100M in venture funding and making a series of high-profile acquisitions. The one thing Medium apparently gave little thought to during this period was how the site would actually start generating revenue.

By 2014, Medium was already well on its way to becoming an online publishing powerhouse. More than 40,000 articles were being published every month. By June of 2014, Medium was attracting upward of 6M unique global visitors per month across desktop and mobile. This was the perfect time to begin experimenting with new approaches to revenue generation.

Medium’s first serious attempt at monetization was Re:Form, a collection centered around design topics that was sponsored by automotive manufacturer BMW and launched in July 2014. Medium agreed to publish 100 articles over a six-month period, all of which would feature prominent BMW branding in the header. BMW’s then-new 4 Series Gran Coupe featured prominently across the publication, and many entries in the series featured promotional video content beneath the articles.

The most interesting aspect of the Re:Form experiment wasn’t where BMW’s branding was or the topics covered in the articles themselves, but rather how Medium approached quantifying engagement with the content. Medium didn’t promise BMW a certain amount of impressions or pageviews, but rather a total reading time measured in minutes. This wasn’t just unconventional from a sales perspective; it also strongly hinted at the underlying technologies Medium was using to measure these attention metrics across the entire platform, not just its native advertising content. It was also pretty radical in that, for sponsored content, the Re:Form articles were largely non-interruptive. This made for a better reading experience, particularly compared to the intrusive video ads that had begun to proliferate across Facebook at that time.

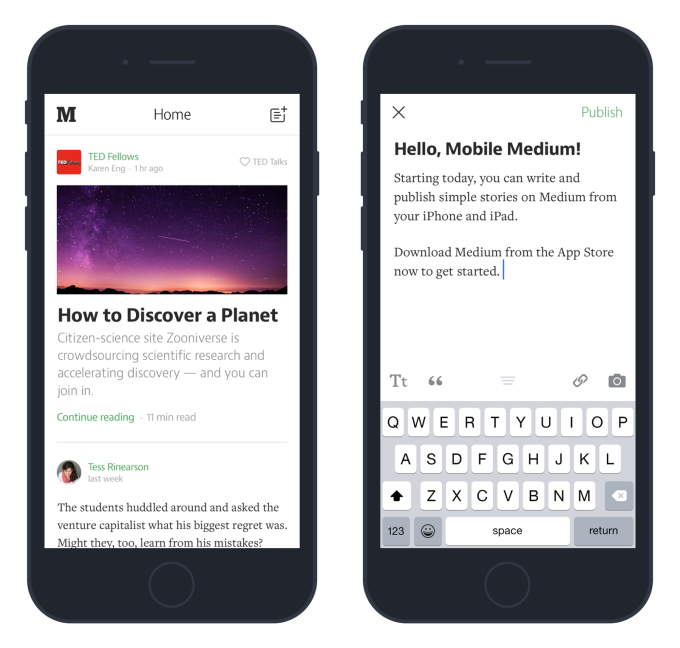

In March 2015, Medium introduced the ability for users to draft and publish posts directly from the platform’s iOS application. This was a logical move. Until that point, Medium’s iOS app had only allowed users to read articles on the platform. It was also one of the most consistently requested features from the site’s growing userbase.

Interestingly, many people thought Medium’s mobile drafting functionality would largely eliminate the “tweetstorms” that had begun to emerge on Twitter by giving users with plenty to say the space to do so. Obviously this never came to pass, given how many prolific Twitter users still thread their tweets into lengthy, one-sided screeds, but it was an interesting use case for adding drafting capabilities to the Medium app. It was also a major accomplishment from a design and user experience perspective. Medium’s mobile drafting tools looked and worked beautifully, even on smaller screens, disproving a long-held misconception that mobile content-creation tools were a losing battle.

Mobile drafting capability wasn’t the only overhaul that Medium underwent in March 2015. The platform’s social commenting features were expanded to allow all readers to highlight text, not just collaborators. Medium updated and launched an improved publishing API that allowed writers to use other editing tools and cross-post articles to Medium. The improved publishing API was quickly integrated into a dedicated plug-in for WordPress blogs, a range of third-party publishing apps like Ulysses, and an integration with automation platform IFTTT.

Although Medium’s minimalist aesthetic was well established by this point, Williams and his team didn’t neglect the appearance of the product as they worked to improve its functionality. The major update in March 2015 also introduced typographical and formatting options, such as the ability to add drop-caps to text, and new font and headline formatting choices to improve readability on mobile. The inclusion of drop-caps was a nice touch visually, but it was about much more than mere appearances. It was another example of Medium’s commitment to changing how we approached and thought about content creation and consumption on mobile devices.

The summer of 2015 brought with it further changes to Medium as a product. In June, the company finally launched its Android app, and debuted its password-less login feature shortly afterward. However, one of the biggest updates to Medium in the summer of 2015 wasn’t a new product feature—it was a radical overhaul of the site’s terms of service when Medium became the latest in a series of high-profile tech companies that took a clearer stance on how they handled abuse across their platforms.

The summer of 2015 brought with it further changes to Medium as a product. In June, the company finally launched its Android app, and debuted its password-less login feature shortly afterward. However, one of the biggest updates to Medium in the summer of 2015 wasn’t a new product feature—it was a radical overhaul of the site’s terms of service when Medium became the latest in a series of high-profile tech companies that took a clearer stance on how they handled abuse across their platforms.

Medium’s new terms of service explicitly forbade many actions that, until that point, had been frowned upon but generally permitted. This included doxxing, hate speech, overt threats of violence, and revenge porn. Medium itself hadn’t wrestled with these problems to the same extent as Twitter had (and still has), but the move was welcomed by advocates.

However, while Medium’s revision of its terms of service took a firm stance on the kind of content it would and would not allow on its platform, it also created tension between Medium and the broader community. Some accused Medium of censorship. Others claimed that smaller publications and independent writers would be held to higher standards than the site’s larger corporate sponsors.

Although Medium’s acknowledgement of the rampant abuse that had plagued sites like Facebook and Twitter was a welcome and necessary step, it put Medium in the uncomfortable position of becoming directly involved in editorial issues across the platform. In an interview with the BBC, Medium’s former head of legal, Sarah Agudo, said that “We aren’t in a position to be arbiters of what’s the truth and what’s right or not.” Except that’s exactly what Medium’s editorial management had become—to the disdain of many members of the Medium community, which felt that the platform’s new approach to moderation stood starkly at odds with the platform’s mission of democratizing online writing and its stated role as “a place for ideas.”

“The reason I think I’m prepared for this is, with Blogger and Twitter, I spent a decade basically enabling people to publish whatever they want as long as it wasn’t stolen or violating any laws. People on my team were very involved in defining content policy at Google and then at Twitter. We’ve always been on the pretty extreme end of freedom of speech. We value that a lot. It would be a pretty extreme case to get in and say, ‘Oh, okay, you can’t publish that.’” — Evan Williams, founder, Medium

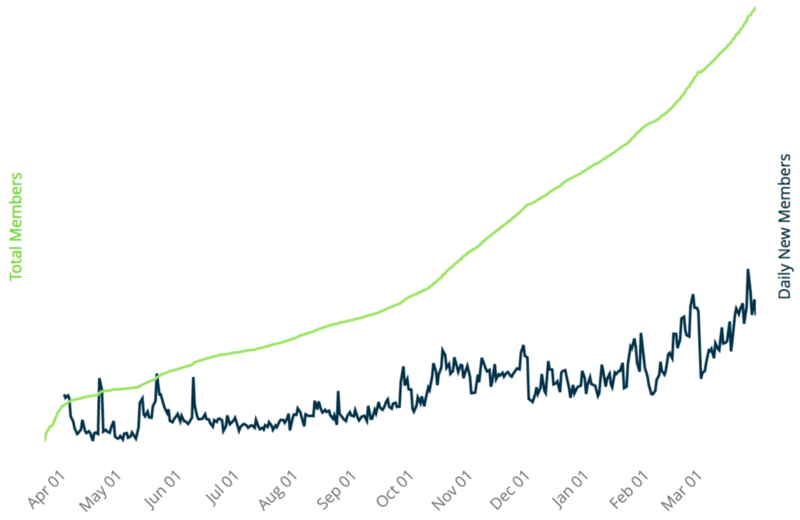

For all the drama that accompanied Medium’s adoption of more restrictive publishing guidelines, it did little to slow Medium’s growth. Between 2014 and 2015, Medium saw an 80% increase in visitors to the site. As of March 2015, Medium readers had spent 1.5M hours reading content on the platform, and the site was attracting more than 25M unique visitors per month.

Growth continued throughout 2015 and well into 2016. While some larger legacy publishers had resisted syndicating content to Medium, many smaller, independent and widely read publications were migrating to the platform en masse. By the end of 2016, dozens of publications known for their insightful, thought-provoking content had migrated to Medium entirely. This included The Awl, Bill Simmons’ The Ringer, The Bold Italic, Electric Literature, Femsplain, Monday Note, and Pacific Standard, among others.

These publications may have lacked the brand recognition of larger, older magazines like TIME and Forbes—but what they did have were loyal, engaged audiences of voracious millennial readers who would happily follow them to their new home on Medium. This was the real brilliance of Medium’s approach to publications. Every blog, magazine, or website that migrated to Medium brought their established audiences with them, which drove traffic to Medium and helped boost the attention metrics that Williams saw as critical to the success of his platform and central to the future of online publishing.

This approach also helped Medium further assert itself as a critical component of the online publishing ecosystem. Once a publication migrated to Medium—and brought its audience along for the ride—it was that much harder for that publication to leave, even if it was dissatisfied with Medium as a platform. This became a contentious point among many publishers. By migrating their blogs to Medium, publishers were bringing their audiences to the platform. Medium, however, was doing comparatively little to return the favor and drive traffic and engagement back to publishers—at least, not in any meaningful way.

In September 2015, Medium raised $57M as part of its Series B round, led by Andreessen Horowitz. The following month, Medium’s logo underwent a modest rebrand. Interestingly—and probably wisely—only Medium’s logo was changed as part of the rebrand. The site’s clean, minimal aesthetic was left unchanged. This made sense, given how fundamental Medium’s sophisticated interface had been to the platform’s growth and popularity.

Six months after rebranding its logo—and just seven months after raising $57M as part of its Series B—Medium raised an additional $50M as part of its Series C led by Spark Capital. Williams and the rest of Medium’s executive team were characteristically tight-lipped about how exactly the company’s new funds were being spent. It’s likely that significant investments were made in Medium’s underlying technology and development of the platform’s social and sharing features, given how attractive this aspect of the platform had been to investors.

“Though we raised our Series B of $57M just last September, we decided to bolster our resources now given the demand we’ve seen for the vision we are building toward. We’re dedicated to building the best platform ever created for great ideas and stories to be launched into the world—and for people to find those stories and ideas that matter to them.” — Evan Williams, founder, Medium

While Medium’s Series C round did indeed bolster the company’s resources, it also put Medium under even greater pressure to solve its monetization problems.

By the time Medium raised its Series C, the company had made little headway in monetizing the platform. Medium’s partnership with BMW’s sponsored Re:form publication had impressed industry analysts with its clear but tasteful branding, but Medium was highly guarded about how much money had changed hands or whether the experiment had been a success. The platform had resisted traditional online ads, but the fact remained that Medium needed to start taking monetization as seriously as its aesthetics.

Speaking at the Ad Age Digital Conference in New York in April 2016, Williams announced a range of new monetization tools—for publishers. Williams said that publications that migrated their existing blogs to Medium would be able to run Promoted Stories by a range of partner brands, including Bose and Intel, both of which were initial partner brands in the pilot program. Edward Lichty, who oversaw content development for the platform at that time, said that sponsored posts were the “first step in how we bring brands together with publishers.” However, beyond the rudimentary details outlined at the Ad Age conference, details were scarce. Publishers would keep “a substantial majority” of the revenue generated by sponsored posts, but how much remained unclear. Williams also revealed that Medium would begin allowing publications to create membership packages, and would be given free rein in terms of pricing and access.

In June 2016, Medium made its second major acquisition when it purchased RSS feed API company Superfeedr for an undisclosed sum. This acquisition was a logical move for Medium. RSS readers had fallen out of fashion, but RSS, Atom, and JSON feed data underpinned some of the most popular services on the web at that time, including Flipboard and Google News. Acquiring Superfeedr gave Medium a ready-made API it could integrate into its existing stack to improve delivery of content from across the platform.

Two months later, Medium dipped into its growing war chest to acquire Boston-based embed code manager Embedly. This was another smart, if predictable, move for Medium. Medium had made its name as a place for long-form writing on the web, but many publications were pushing the boundaries of presentation by incorporating visually stunning, media-rich stories that included audio, video, and animation. Acquiring Embedly allowed Medium to offer more than 100 embedding integrations to its platform almost immediately, which could then be rolled out to publishers.

Medium’s focus on aesthetics and the experience of writing and publishing on the platform earned the service a strong, loyal following early on. The introduction of key functionality such as highlighting and mentions added a much-needed social element to the service, and Medium scored several crucial wins by attracting well-known publications to the platform. However, Medium’s focus on design and experience had left the platform vulnerable monetarily. By choosing to experiment with new business models, Williams was leaving potentially millions of dollars on the table in lost advertising revenue—a problem Medium would continue to struggle with for the next several years.

2017-Present: Challenging the Attention Economy

By the end of 2016, Medium was riding high. Many respected editorial brands had migrated completely to Medium and many more were considering it. The platform’s high-profile writers had attracted a legion of new readers who were eager for the kind of in-depth, long-form writing that Medium had helped popularize. The company was confident about its new Promoted Stories for publishers.

The future looked bright—until the company was forced to lay off one-third of its staff in early 2017 following the catastrophic failure of its first real attempt to monetize.

Williams broke the news in characteristic fashion—by publishing a post on Medium. In the post, Williams praised the work of his team and lamented the financial pressures that had forced his hand. Around 50 people were laid off in January 2017, roughly one-third of the company’s entire workforce. The majority of the redundancies were made across Medium’s sales and business development teams.

“We believe there are millions of thinking people who want to deepen their understanding of the world and are dissatisfied with what they get from traditional news and their social feeds. We believe that a better system—one that serves people—is possible. In fact, it’s imperative. So, we are shifting our resources and attention to defining a new model for writers and creators to be rewarded, based on the value they’re creating for people.” — Evan Williams, founder, Medium

Medium had been cagey about the performance of its sponsored publications, but it was even less forthcoming about the reasons behind the layoffs. However, there were several indications that Medium’s nascent advertising options simply couldn’t compete with traditional PPC and social advertising options offered by Google, Facebook, and even Twitter. According to Medium, the platform was attracting upward of 60M unique visitors per month as of November 2016—a 140% increase from the 25M unique monthly visitors the site observed a year previously. However, this was still relatively low compared to rival ad networks, many of which had significantly more granular targeting parameters and remarketing capabilities.

Two months after it laid off a third of its staff, Medium announced the launch of its paid subscription model. In the Medium post announcing the new business model, Williams explained that subscriptions would be priced at an introductory rate of $5 per month, and that subscribers would enjoy an improved reading experience based around a limited feed of articles carefully selected by expert curators. Williams also stated that 100% of the revenue generated by new memberships during the first few months would be paid to “writers and independent publishers who have important work to do.” This was an important element of Medium’s user growth strategy that would compliment the platform’s new monetization strategy.

“We need a system that funds stories and ideas not just based on their ability to attract attention, but on their value to readers. This is the system that Medium is building, and as a founding member, you’ll get to help tell us what’s most valuable and how we spend that money.” — Evan Williams, founder, Medium

From a business perspective, the move to a subscription model made sense. Medium’s attempts to monetize the platform via native advertising appeared to have fallen short of the company’s expectations, and the inclusion of traditional display ads would have done significant damage to Medium’s reputation and ruined the platform’s stylish editorial aesthetic.

From the perspective of writers and independent publishers, however, Medium’s subscription model was nothing less than a betrayal of Medium’s stated mission to be a meritocratic home for long-form writing.

In May 2017, several of the publications that had migrated their entire sites to Medium reversed course. Pacific Standard’s Editor-in-Chief, Nicholas Jackson, emphasized his publication’s renewed focus on increasing both digital and print subscriptions as the primary motivation for leaving Medium. Other publications were more direct in their reasoning. Neil Miller, founder of movie review site Film School Rejects, said that Medium’s policies were preventing FSR from paying contributors to actually create content for the site.

One of the major criticisms of Medium’s new membership model was that it lacked the revenue guarantees that had attracted so many publications to the platform initially. Even publications that remained on Medium after it scrapped Promoted Stories were skeptical about what the platform could offer publishers.

Other analysts and industry writers were far less reserved in their criticism of Medium’s new direction.

“Switching from an experimental advertising model to traditional subscriptions is a cop-out. Medium abandoned their mission. Now there’s a paywall that stands between Medium’s loyal readers and the best of what the platform has to offer. It’s a huge letdown. The idealistic thread that runs through all Ev Williams’ ventures is starting to fray.” — Theo Miller, contributor, Forbes

There were two major problems with how Medium went about transitioning from native advertising and sponsored content to its membership model:

- The soft paywall that Medium’s membership plan introduced was seen as highly divisive for a platform supposedly dedicated to democratizing long-form writing and essentially split Medium into two distinct tiers

- Although Medium promised that 100% of revenues would be paid directly to writers, payments were calculated based on a variety of factors—including traffic

Medium’s problems with its new membership model were as ideological as they were financial. The introduction of the platform’s soft paywall directly contradicted everything Williams had set out to create. The fact that Medium’s membership program was both necessary and inevitable did little to mitigate the damage it did to Medium’s brand.

The second major problem was that, given that revenues were tied directly to how much traffic writers and publications received, even the most excellent content would only earn writers and publishers a pittance if they couldn’t bring in significant traffic. This put individual writers, freelance journalists, and smaller independent publications at a major disadvantage to larger, more established publications with bigger audiences.

So much for the democratization of online writing.

Even as writers and publishers fled Medium for greener pastures, the company continued to invest in both the platform and new content formats. In May 2017, Medium launched audio versions of certain stories published on the site. Designed to appeal to audiences that were eagerly devouring incredibly popular investigative journalism podcasts such as Sarah Koenig’s Serial, Medium’s audio stories were read by professional voice artists and performers. The catch? Audio content was restricted to Medium subscribers. Undeterred by criticism about its new gated approach to premium content, Medium doubled down on audio in June 2017 when the company acquired struggling SMS app Talkshow for an undisclosed sum. Talkshow had been developing a podcasting product called Episode toward the end of 2016, but Medium appeared to be more interested in acquiring Talkshow’s senior talent—including Michael Sippey, Talkshow’s former CEO who also worked as VP of Product at Twitter and later became Medium’s VP of Product—than Episode as a product.

One of the biggest changes to Medium as a platform came in August 2017 when the company debuted Claps, its latest audience engagement feature. Claps allows users to “clap” for a story in much the same way as Reddit allows users to “upvote” user submissions. However, unlike similar systems on other platforms, Medium’s Claps were unique in that users could clap for a story as many times as they liked. The more claps a story had, the greater the visibility of the story.

One of the most interesting aspects of Medium’s Claps system is that it aligned closely with Medium’s original mission to quantify quality in online content, but it was also a significant risk for the platform. Since its inception, Medium wanted to quantify the quality of content in a way that no other platform had before, and Claps was an interesting approach to the problem of quantifying the quality of Medium’s content. Allowing users to clap as many times as they wanted gave audiences much more room to express their support for certain articles, but it was also a system that was at risk of abuse and manipulation for the sake of visibility—and later, revenue—a vulnerability that remains today.

“The Recommend—our version of a Like or upvote or fav—has been our explicit feedback signal since almost day one. Explicit feedback is the most valuable signal, both for authors and the Medium system. But a simple, binary vote has its limitations. It shows you how many people thought something was good, not how good was it?” — Katie Zhu, former Engineer and Product Manager, Medium

Claps proved popular with users. However, Medium continued to struggle with its monetization problem. These problems came to a head in October 2017 when the company announced the launch of its Partner Program.

At first glance, the Medium Partner Program was the solution Williams and his team had been looking for. It would reward genuinely great content that was engaging readers. It would pay writers directly, and wouldn’t deduct the typical middleman fees to advertisers or ad networks. It would create a consistent, reliable revenue stream for Medium as a company.

However, it quickly became apparent that, while Medium’s Partner Program was undoubtedly good for the company, its value to writers and publishers was far from clear. For one, Medium did little to explain precisely how writers would be paid. The company stated that payments would be calculated primarily by engagement, and that the Claps system would be integral to this system.

According to Medium, approximately 83% of writers who published stories behind Medium’s paywall were paid for their content:

- The largest single payment made to an individual author was $2,279

- The largest payment made to an individual publication was $1,466

- The average payment across Medium’s Partner Program was $93

However, many users—including participants in the Partner Program’s beta-testing period—found that despite receiving similar volumes of Claps and attracting comparable traffic to their work, there were considerable disparities in payments. Others found that Medium appeared to be promoting members-only articles much more heavily than those published by non-members. Still others found that “locking” stories (i.e., making them available only to subscribers) resulted in higher payments for stories of comparable performance to unlocked stories. Post after post after post was published by Medium writers hoping to give others more insight into the viability of Medium’s Partner Program.

Some variance in payments was to be expected, as was Medium’s reticence to disclose exactly how its payments were calculated. However, the disparities created further division among Medium’s already-fractured writing community. It also raised yet more questions about Medium’s commitment to the kind of transparency Williams had championed during his platform’s earliest days.

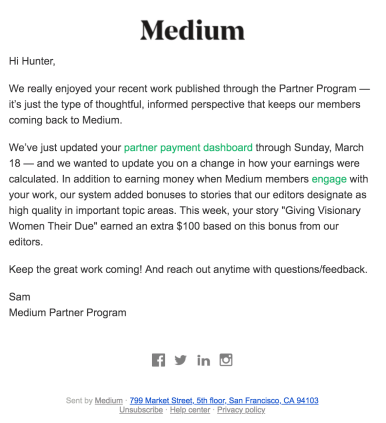

The next major change to Medium’s Partner Program came in March 2018 when contributor Hunter Walk received an email from Medium telling him he’d been awarded a $100 bonus for the quality of his members-only piece, Giving Visionary Women Their Due.

Medium later confirmed that this payment was among the first cash bonuses that the platform would pay contributors for quality work. Medium also confirmed that bonus payments would be limited to $100, at least initially. Despite the somewhat vague nature of how Medium’s editorial team determined which articles were worthy of bonuses, it was a small but important step toward trying to regain some of the credibility Medium had lost among the online writing community.

“Medium Editor’s bonuses are part of our continuing effort to build a system that pays writers based on value to readers, not click value to advertisers. We’re focused on quality, and on building the best subscription-based platform for reading and writing, where people can discover unique ideas and perspectives all in one place. We want to help create a path for writers that hasn’t existed before.”

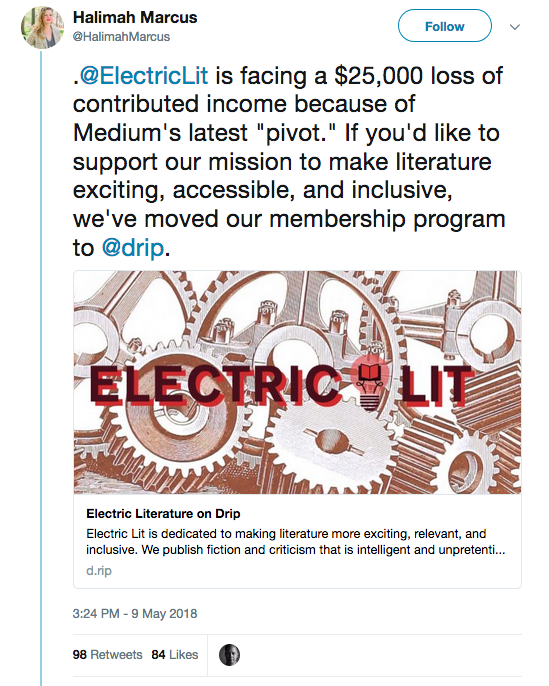

However, much of the goodwill Medium had salvaged by introducing cash bonuses for quality work was lost in May 2018 when Medium abruptly retired the functionality that allowed publications to establish their own paywalls.

Almost overnight, Medium had jeopardized the financial futures of hundreds of small, independent publications. This included the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism, whose founder Chris Faraone first reported the change via Twitter, and Electric Literature, one of the very first publications to migrate its entire blog to the platform. Electric Literature’s Executive Editor, Halimah Marcus, also took to Twitter to voice her displeasure at Medium’s latest “pivot” and inform readers of Electric Lit’s move to the Kickstarter-funded Patreon competitor, Drip.

For all its design innovation and the significant impact Medium had on the broader world of online publishing, its ongoing struggle to turn a profit and regressive attitudes toward gating content have done considerable damage to Medium as a brand and a business. However, while many industry analysts have been quick to criticize Medium for its failings, they also typically fail to mention the sheer scale of the problem facing the online publishing industry. The problem of successfully monetizing online content—and how to achieve a balance of editorial quality and sustainable revenue—has plagued the publishing sector as a whole practically since the inception of the internet. This is not an easy or straightforward problem to solve.

“Ev chose the hardest thing to do. He said, ‘I want to make publishing profitable.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, so does everyone else.’ How far along are we? Somewhere between zero and half a percent.” — Biz Stone, co-founder, Twitter

For all his missteps, few people have done as much as Evan Williams has to try and make online publishing better, more rewarding, and ultimately, more profitable. Although Medium continues to attract writers and publications thanks to its elegant presentation, management problems and Williams’ reluctance to embrace the only proven, lasting business model in publishing—advertising—could spell doom for the company.

Where Could Medium Go From Here?

Evan Williams has spent almost twenty years trying to revolutionize online publishing — to varying degrees of success. Where could Williams’ company go from here?

1. A return to sponsored content.

Williams’ refusal to capitulate to investor pressure by running ads on Medium is admirable, but it also severely limits his company’s options when it comes to monetization. Given Medium’s historical resistance to traditional online advertising and the importance of the platform’s minimal aesthetic as a competitive advantage, it’s possible that Medium will revisit its former experiments in sponsored content as it did with BMW’s Re:form publication in an attempt to generate additional revenue.

2. Restructuring of Medium’s Membership plan.

Medium has taken too much venture capital funding to avoid an IPO in the future. The only viable monetization play Medium has at this time is its deeply unpopular and divisive Membership plan. If Medium is to appease investors in the short term, it seems likely that Medium will continue to refine and adjust its Membership plan to attract more subscribers.

3. Greater emphasis on audio content.

Given the increasing popularity of audio content such as podcasts, it would make sense for Medium to expand into this area in an attempt to grow its userbase significantly and potential Membership plan revenue along with it. However, to succeed, Medium would have to be highly strategic and tactical about making a lateral move like this, given the already intense competition in the audio content space. With more than 48M Americans listening to podcasts on a weekly basis—an increase of more than 6M over listenership figures for 2017—podcasts and audio content could be a lucrative lateral move for Medium as its monetization pressures mount.

What Lessons Can We Learn From Medium?

Few products have attempted to tackle as ambitious a problem as how to truly revolutionize online publishing as Medium. What lessons can entrepreneurs learn from attempting to transform such a vast industry with such existential challenges?

1. Defying conventional wisdom can work—at least initially.

For all its mistakes, Medium has always been a strongly user-focused company and product. Medium succeeded because it looked beautiful and felt fresh, but it also succeeded precisely because it resisted conventional wisdom about online publishing models by refusing to run ads on the platform.Whether you’re still seeking seed funding or you’ve been in operation for a while, think back to when you originally began approaching people about your product idea and the advice people gave you:

- Were there any points at which your entrepreneurial instincts stood at odds with the advice that potential investors or fellow founders gave you? Did you cave and end up following that advice, or did you resist the temptation to take the easy way out? How could your product benefit from taking an unorthodox or unconventional approach to solving the problems you’re trying to solve?

- If you’re resisting conventional wisdom, ask yourself why you’re reluctant to follow the pack. Are you truly confident in the viability or originality of your idea, or are you being deliberately contrarian for its own sake? There’s nothing inherently wrong with going against the grain, but it’s vital to understand why you’re taking the approach you’re taking.

- How long can you realistically expect to try things your way before it begins to jeopardize the future of your product or the growth of your business? Williams’ experience at Blogger and Twitter afforded him some leeway that gave Medium some freedom to experiment that other start-ups might not have. Put another way, have you identified a clearly defined cut-off point for experimenting with your business model?

2. Idealism isn’t always enough.

To his credit, Evan Williams has devoted much of his professional life to changing how we think about writing and publishing online. However, as Medium’s ongoing struggles to reach profitability and its tempestuous relationship with writers have demonstrated, a laudable mission isn’t always a viable business idea.Think about your company’s mission or overarching goal, then answer the following—and be honest:

- Is your idea truly financially viable? Medium’s real challenge wasn’t just changing perceptions about or the popularity of long-form writing online, but also finding a completely new way to monetize online content. Can you solve an urgent problem in your space and create a sustainably profitable business?

- Remember, finding a sustainable business model doesn’t have to be a binary choice. If you’re concerned about the long-term financial viability of your product, can you identify a middle ground between solving an idealistic problem by genuinely innovating and creating a scalable growth strategy?

- If you were to make such a pivot, how would you handle this from a branding perspective? For Medium, the introduction of its Membership plan was a sound business decision but it also did significant damage to perceptions of Medium as a brand—particularly among the writers, journalists, and publications that helped Medium succeed in the first place. How would you go about making this kind of transition?

3. Make sure there’s a definite need—or a strong desire—for your product.

Ultimately, Medium’s biggest challenge—and greatest weakness—is that there’s no real need for it as a company or a business.Medium certainly helped redefine online writing, particularly the kind of in-depth, long-form content that had mostly fallen out of fashion prior to Medium’s launch, but that doesn’t change the fact that there really is no urgent need for Medium as a platform. Unlike traditional magazines and publications that rely on brand association in addition to quality content as a vehicle for subscriber growth, Medium is closer to an aggregator than a true publisher—and it’s much harder to cultivate reader loyalty to a platform than a publication.

Think about your product and its place in the broader ecosystem of your sector or industry:

- Is your product essential or highly desirable? Most entrepreneurs would probably hope their products are both, but in practice, there’s often a pretty clear distinction between the two.

- If your product is essential, is it also genuinely fun, entertaining, or exciting to use? If not, why not? How could you improve the experience of using your product to be fun as well as functional? Don’t lose sight of the fact that “useful” doesn’t necessarily have to mean “utilitarian.”

- If your product is highly desirable, how can you make your product integral to your users’ daily lives? If you’re relying on the experience of using your product to keep them coming back, how can you cultivate a more meaningful need for your product?

A Place Where Words Still Matter

Medium hasn’t always gotten it right. To this day, Medium remains a contentious platform for experienced journalists and aspiring writers alike, and the company seems no closer to conclusively solving its monetization problems once and for all. However, despite its numerous missteps, Medium has done more to change the way we think about and consume long-form written content that any other site, platform, or company.

It’s hard to imagine what the landscape of long-form publishing would look like today without Medium’s contributions. It’s also hard to imagine how Medium will overcome its greatest challenge—monetizing without sacrificing everything it stands for—without alienating writers and readers further.