When to Commit—and When to Pivot

Early in the life of your company, there’s one question you have to keep answering: Do you continue what you’re doing, or do you pivot?

You hear a lot of stories about successful pivots—ones that happen right before a founder or team was about to quit. A few good examples: “Slack pivoted from a gaming company to a B2B workflow tool,” or “Instagram started out as a Foursquare clone.” Pivoting isn’t a bad thing, but a lot of founders misunderstand when it makes the most sense to pivot.

The problem I see a lot of people run into is that they haven’t been deliberate about learning—and then making tactical changes to their product or go-to-market strategy based on what they’ve learned.

Before you decide to pivot, ask yourself:

What have I learned that makes me want to pivot?

There are three types of pivots you can make with your business. Each comes from a different type of learning:

- Product Pivot: You learn that one part of your product is way stickier than the rest, and your customers care a lot more about it.

- Customer Pivot: You learn that there is a new segment of customers willing to pay more for your product than your current customers.

- Problem Pivot: As you talk to your customers and do research, you discover they have way bigger problems than the ones you’re trying to solve.

It’s important to note that each type of pivot requires making a big change to your business model, which isn’t something to take lightly. The only time you should “pivot” is when you learn something so significant about your product, customer, or problem, that you have to make a substantive change to your business.

Let’s dig into the different types of pivots, using examples to illustrate what a successful pivot looks like in each of the three categories.

Slack’s Product Pivot: From MMORPG to Internal Communication Tool

Slack began as Glitch, the never-ending game.

A product pivot happens when you undertake a drastic shift in what you’re building. Slack is one of the best-known examples. Slack was born out of the failure of Glitch, a venture-funded “never-ending” video game. While Glitch never caught on, their internal tool for communication did.

To collaborate remotely on Glitch, the team behind it built an internal chat tool, which they kept adding features to over time. They hacked together a database to log and archive information so that people didn’t have to be online to receive messages—they could log back onto the tool and see everything they had missed. They built features for searching the messages database. They added basic file-sharing, and more.

The more files, messages, and tidbits shared over this internal chat tool, the more time team members spent using the internal tool across teams. While Glitch struggled to acquire and retain new users, the team building it found their internal chat tool to be insanely sticky. By the time Glitch shut down in December 2012, the team had grown to 45 members—with only 50 internal emails logged on the company-wide list. Their chat app was so sticky that it completely replaced email within the company.

As the team was figuring out its next move, Cal Hendersson, one of the co-founders, thought:

“We knew that whatever it was we did next, we didn’t want to do it without a similar system.”

The early, homegrown version of Slack had solved a huge problem for the team. When they looked around at the competition, they saw a $100 million revenue opportunity—and nothing as good as what they’d already built. So they pivoted full-throttle into building Slack.

The Pivot

Early prototypes of Slack.

Slack wasn’t a “Hail Mary” pivot. Slack was built on top of everything the team had learned from using their tool for over three years—and from the failure of Glitch.

Glitch had introduced a new open-ended way of playing video games, without levels, bosses, or combat. As Butterfield points out, the “biggest design challenge with Glitch was prioritizing what you had to get introduced to.” Outside of a core group of dedicated fans, they had trouble getting enough people to play Glitch and stick around.

Slack also started with a unique vision: to transform the way we communicate at work. As the team incrementally rolled out their messaging product from a handful of companies to a list of 15,000 beta testers, they focused obsessively on figuring out how they could educate and help customers use Slack better—something they had tried and failed at with Glitch. They responded to every piece of customer feedback, support email, and tweet.

Their key finding came from asking users what tool they were using prior to Slack. More than 70% responded: “Nothing.” Digging deeper, Slack found that these customers had hacked together their own solutions, from Hangouts to Facebook Groups to Skype.

Most people weren’t thinking about internal messaging as a software category, like issue-tracking or productivity. Slack set out to change that. Two weeks before Slack launched, Stewart Butterfield sent an internal memo to the entire company:

We are unlikely to be able to sell “a group chat system” very well: there are just not enough people shopping for group chat system…However, if we are selling “a reduction in the cost of communication” or “zero effort knowledge management” or “making better decisions, faster” or “all your team communication, instantly searchable, available wherever you go” or “75% less email” or some other valuable result of adopting Slack, we will find many more buyers.

While building Glitch, they discovered a lot of internal benefits to using their tool—namely, less email and more productivity. Slack was only successful because it was able to translate those benefits to a customer-facing product.

If you’re trying to figure out whether to pivot your product, ask these questions:

- Is one part of my product or feature stickier than the others? Why?

- Which product features correlate most highly to long-term retention?

- Where are people spending the most time in my app?

No matter how much research you do ahead of time—and yes, you need to do research—it’s hard to predict which part of your product will be the stickiest until testing it with real, live customers. The trick is to rapidly learn why one feature works, or another doesn’t.

Pivoting your product means maximizing what you learn from your customers about what you’re building. Sometimes though, what you’ll learn is that you need different customers—which takes a different kind of pivot.

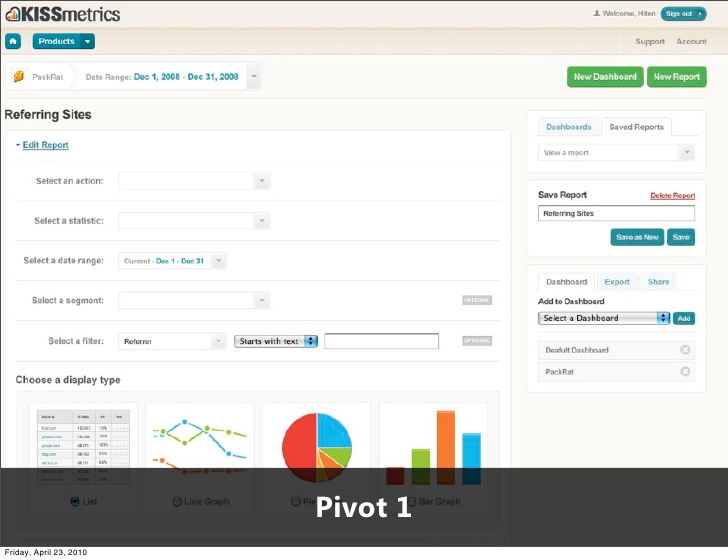

KISSmetrics’ Customer Pivot: From “Analytics for Everyone” To “Analytics for Marketers”

If you learn that your early customer base won’t be enough to support your business, you can’t build a different product for the same customers. You have to do a customer pivot, and find higher-value customers.

A good example of this is how we pivoted one of the early versions of KISSmetrics, which focused on providing analytics to everyone. We had assumed that people knew what they should measure, and wanted the ability to customize their analytics setup.

It looked like this:

In theory, game developers could track user engagement by comparing user attributes like age or gender against number of sessions. SaaS developers could track events like how many files people shared a day. While it was a good idea, it didn’t work out that way in real life.

After we launched our MVP, we found that people didn’t always know what metrics to track. They didn’t want customizable dashboards because they didn’t know what to put on them. Most importantly, we learned that not all customers were even willing to pay for analytics.

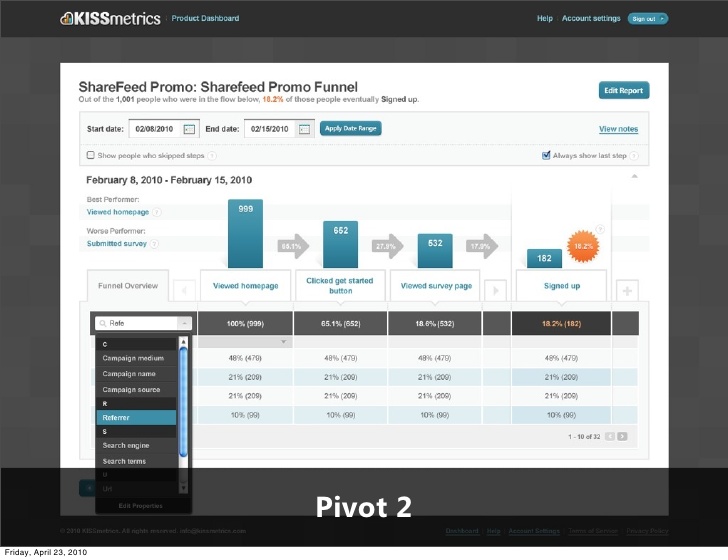

So we pivoted to focus on a new group of customers: Internet marketers.

The Pivot:

When you build a wide product that anyone can use, you run into the danger that no one will use it. We were running into this exact problem at KISSmetrics. To get people to pay for an analytics product, we had to demonstrate value right off the bat by showing them metrics they cared about. That meant we couldn’t “build for everyone.” We had to focus our product around solving a specific problem, for a specific customer.

By doing research on our target customer, we found that internet marketers were having the biggest problems. They spent a lot of time trying to figure out Google Analytics, and copy-pasting data into Excel spreadsheets. So we went back to the drawing board. We did around 50 different customer development interviews to figure out what marketers really needed.

This time, when we pivoted KISSmetrics, we focused on building out a product that would help marketers do their jobs better. We didn’t pivot our core product idea or our larger business model. We simply focused in on what internet marketers needed:

- Actionable analytics: A lot of marketers didn’t necessarily know what to look for in Google Analytics. They wanted a clearer picture of how specific metrics would help them make money. We focused on providing our customers with analytics that told them about their business—what the LTV of their customers were, sources of referral traffic were the most valuable, conversion rates, and more.

- Data around conversion rates: We built our product at KISSmetrics around a conversion funnel. We used event data that customers had from the past, and created a new way for them to visualize their conversion funnel right-to-left.

We’d already solved the trickier, technical challenges around analytics with our earlier product. This was stuff like automatically tracking all web visits and tying this data to free trial sign-ups and conversion. With our customer pivot, we took this and made it valuable to the people we knew would pay for it: internet marketers.

To figure out whether to pivot around your target customer, ask these questions:

- Who are your highest-LTV customers? What do they use your product for?

- What customers might use your product that aren’t using it now? What’s their LTV?

Maybe you have the right product and business model, but discover that your current customer base isn’t lucrative enough to support the business. If that’s the case, you have to figure out whether there are other customers worth pursuing.

Early on in your business, it’s especially important to focus on who’s willing to actually spend money on your product. But what do you do when find find that there’s a more pressing, urgent problem they need solved?

Qualaroo’s Problem Pivot: From Freemium Hub to Customer Insight

When you talk to your customers and learn that they have a bigger pain point that you’re not solving for, you may want to consider a product pivot.

As an example of a product pivot, let’s look at Sean Ellis’ company, CatchFree. CatchFree began as a community-driven website that makes it easy to discover and share the best free web apps. The idea behind the company was to create a hub for freemium products, allowing free services to grow from each other’s users rather than through paid acquisition.

In 2011, upon the launch of CatchFree, Sean Ellis wrote that “customer acquisition is the number one challenge for a freemium product.” The idea was that CatchFree would help freemium products leverage a centralized database of users to grow more efficiently—without having to spend a lot of money on pay-per-click ads.

What the CatchFree team found was that app publishers generally didn’t need to drive more traffic to their free product.

As Sean Ellis wrote on his blog:

“Since launching at TechCrunch Disrupt last year [CatchFree] has attracted over 1.8 million users and collected detailed ratings for over 1000 apps. But surprisingly, app publishers were more interested in the structured insights we uncovered than the traffic we were sending.”

Freemium business owners needed more insights around that traffic in order to sell customers the paid product. These customers were getting more value from the insights that CatchFree provided them than the actual traffic volume. So they pivoted around the problem.

The Pivot

Qualaroo Landing Page, 2016.

Instead of trying to help freemium businesses drive more traffic, CatchFree began helping businesses develop a better qualitative understanding of their customers.

A year after launch, CatchFree built out and launched MustHaveScore.com—a widget that helped companies get user feedback better and faster. It was an instant hit. MustHaveScore.com validated a very different problem than the one CatchFree set out to solve—but one that was also potentially more interesting and lucrative. At the time, Sean Ellis wrote on his blog:

“Through the execution of MustHaveScore we found that many people were looking for a more elegant way to collect feedback from their users. They also wanted the flexibility to ask their own questions. It became clear that what they really wanted was KISSinsights, so we approached our friends at KISSmetrics about buying it.”

KISSinsights was the survey tool we’d built at KISSmetrics to help people get open-ended feedback on our site. It already fit into the direction that CatchFree was moving. So Sean acquired KISSinsights and rebranded it and CatchFree as Qualaroo.

Qualaroo still targeted fast-growing startups, but with a completely different product. Qualaroo helped website owners understand why people made decisions on their sites, and nudged them through a conversion funnel to lead-capture forms and live chat.

Building CatchFree allowed Sean Ellis and his team to figure out what the big marketing opportunities were, and then pivot to a different one.

To figure out if it’s time for a problem pivot:

- Is the problem I’m solving really a problem?

- What other problems are my customers facing?

Don’t be married to solving a specific problem. The biggest problems your customers have won’t be the most obvious ones to you, especially when you’re starting out. Staying sensitive to the broad spectrum of pain points your customers are feeling will help you identify new—and potentially larger—opportunities.

What Can You Learn About Your Customers?

If you think your startup needs to pivot, pause for a minute. Ask yourself if you’ve actually learned something that makes you think you need to pivot—or if you’re just trying to make an uninformed change.

A lot of startups make premature changes early on for the following reasons:

- Lack of product-market fit: When you’re not seeing much traction with your early idea, it’s tempting to make changes to your product and business just to see what sticks. But if you’re making changes based on a hypothesis and learning, you end up shooting in the dark. If you’re in this situation, check out this SlideShare I made on how to qualitatively assess product-market fit.

- Lack of time: Whether a startup is venture-funded or bootstrapped, there is limited runway before the business runs out of cash. Sometimes you’ll make changes to your business or product because it feels like you’re taking action, which can cause you to spend a lot of time and money unnecessarily. Instead, ask yourself why you want to make these changes. What did you learn about your customer or the competition that makes you feel a change is necessary? What use-cases does your change solve, and how valuable are they? If you’re struggling to learn about your customers, read this article I wrote around how to research the customer.

- Uncertainty business viability: A lot of times people ask: “Should I pivot?” But, the question they really want answered is: “Should I quit, or keep going?” The second question is much harder to answer because it means you have to make a decision about the very existence of your startup. If you aren’t sure whether to quit or keep going, listen to this episode of the Startup Chat where I talk about how to make deliberate, objective decisions about when to keep pushing, and when to call it quits.

A successful pivot doesn’t begin or end with the pivot itself. It’s the result of a deliberate process around how you learn—and then optimize your business around those learnings. Slack, KISSmetrics, and Qualaroo succeeded because they were able to rapidly turn early gaps in their knowledge into much larger opportunities.

The common thread is that no successful pivot happens without a lot of assumptions getting smashed. What matters in the end isn’t whether you’re “right” or “wrong”—it’s how quickly you learn from all the ways you’re wrong, and how you execute accordingly.